“There is a difference between losing something you knew you had and losing something you discovered you had.

"One is a disappointment. The other feels like losing a piece of yourself” Anonymous

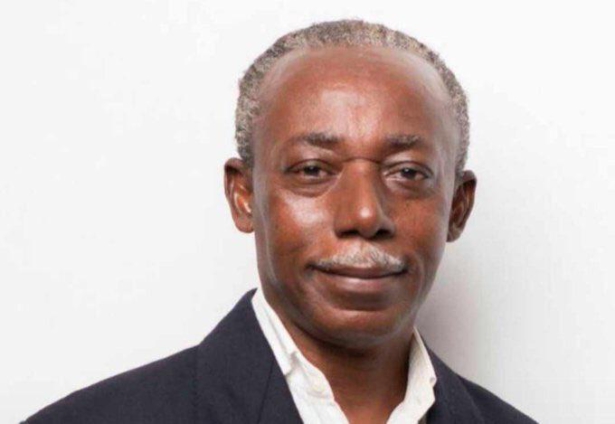

In a law faculty where regimented learning fueled by an obsession for exams was the order of the day, Professor Emmanuel Yaw Benneh cared about knowledge and ideas in and of themselves.

He cared whether we knew what we were talking about and that we were not unthinking parrots of other people’s learning.

He cared about the written word—how we put our ideas on paper. He saw his role as one of raising thinkers even if it is in a system that treats robust thought as a luxury.

His tutorials were intense. He would contest what you were saying even before you were done talking.

If you came to him with what J.D Harris or Malcolm Shaw said be prepared to back it up as if you had thought it through.

And, don’t come to him with a decided case assuming that was final on any question of law.

He would flip principles on the head just to see whether you could come back by thinking on your feet.

For him, authorities were starting points in creative engagement with the ideas and principles that animate the law.

He was a thoroughgoing Oxbridge scholar—an intellectual tradition he held proudly.

It was easy to find his intensity unbearable and to even avoid it.

You did not have to choose his tutorials and many deliberately did not. But he was intense because he cared.

When he rattled you at tutorials, it was not personal, he would easily have a hearty chat with you on his way to his car—that characteristic Volkswagen Golf.

I know this all too well. In my first tutorial with him, he rattled me and made me realize I did not know what I was talking about, nobody in the room knew what they were talking about that day even though we all seem to have read.

On one such days, I asked him whether he would be interested in reviewing my essays on the topics we would be discussing weekly at tutorials and he agreed.

So after every tutorial, I would be by that Volkswagen to submit my essay. I realized even at a personal level nothing changed.

The essays returned with full paragraphs cancelled, others written across them “why?” “where?” “what do you mean?” “so what?”. I questioned whether I had made a mistake. Did I really try to match wits with our very own Hugo Grotius?

The bar with him just went up and up and up each week. But with each stroke of the pen, he was shaping my thought process.

He would eventually give me an ‘A’ in that paper, but like any great professor, that was not the point, it was how I thought and wrote about the ideas I was engaging that mattered to him.

I was drawn to Professor Benneh because he validated me, even though his was tough love.

I shared with him the belief that uncritical accumulation of what authorities have said alone was no way to go about the law.

That law was a product of times and places and ideas and power relations—nothing is to be taken as a given. He was contrarian in a way that inspired my own confidence.

Bowett, Brownley, Shaw and others were not some hallowed sources of legal principles that could not be challenged. He expected us to question those ideas every time he said sagaciously “but today, we know…!”

On his own, Professor Benneh was not afraid to take on mainstream ideas and let us know what his own views were. On his pet topic in Public International Law—Use of Force—he was at his full powers, bending the currents and intricacies of world history and politics with his outstanding intellect.

Crushing one thousand years of world events into a two-hour lecture, connecting dots from St. Augustine to Donald Rumsfeld, St. Thomas Aquinas to George Bush; from Rome to Washington DC to The Hague.

He would expose the biases of St. Augustine and St. Thomas Acquinas on the so-called just war doctrine; he would take on self-serving interpretations of International Law by the Bush and Obama administrations on the War on Terror and the Responsibility to Protect respectively.

He worried that in a world run by ideas, if we did not know our bearing we would become accessories in our own oppression.

I did not try to advance my relationship with Professor Benneh beyond my time “at his feet” and we did not speak since I left. I thought there would be time for that.

That someday I would return to meet him for such further conversations and debates like the ones we had at tutorials.

Now, in the most chilling way, that possibility is lost forever.

But I am grateful for the moments we had him and I will remember the anecdotes. Stories about running into the great Professor Stephen Hawking at the University of Cambridge—a story he told on the morning we got the news of the legendary professor’s passing.

I will remember vintage moments, too. For instance, responding to an answer from a student that the United Nations’ role was to ensure peace and security; “at where? In your village? No! International Peace and Security” he thundered across the hall.

As well as stories he was told as a child that he shared about how the people of Kumasi responded to events during World War II; “Hitler e ba o” (Hitler is coming) someone will scream and people will actually run home.

I will miss him; his gait, his rhetoric, his wit, his Cambridge manner, his George Williams fashion sense and of course, that Volkswagen.

But he will live on in every paragraph I write and he in the heads of most students who ‘sat at his feet’ (he would say).

Like Mr. Keating (played by Robyn Williams) to his students in the 1989 Hollywood film Dead Poets Society, Prof taught us to responsibly break with convention, to savor knowledge, to aspire to a higher purpose, to embrace the hard work of knowing what we are talking about.

To those who appreciated it, he was our Captain. And like the poet, Walt Whitman, to his own Captain (Abraham Lincoln) who died a most gruesome death wrote:

Here Captain! Dear Father!

This arm beneath your head;

It is some dream that on the deck,

You’ve fallen cold and dead

(From the Poem O Captain! My Captain!)

Hugo Grotius, the father of International Law and easily one of Professor Benneh’s greatest influences wrote; “A man cannot govern a nation if he cannot govern a city; cannot govern a city if he cannot govern a family; he cannot govern a family unless he can govern himself; and he cannot govern himself unless his passions are subject to reason”.

Here goes a teacher who loved his craft. A scholar who lived what Hannah Arendt called ‘a life of the mind’ and taught his students to rise above mindless imitation—to reason; to govern themselves, so they might govern more.

Damirefa due

Farewell Prof. How I wish we had more time.

***

The writer is an aluminus of the University of Ghana's School of Law.

Latest Stories

-

GSTEP 2025 Challenge: Organisers seek to support gov’t efforts to tackle youth unemployment

14 minutes -

Apaak assures of efforts to avert SHS food shortages as gov’t engages CHASS, ministry on Monday

38 minutes -

Invasion of state institutions: A result of mistrust in Akufo-Addo’s gov’t ?

54 minutes -

Navigating Narratives: The divergent paths of Western and Ghanaian media

1 hour -

Akufo-Addo consulted Council of State; it was decided the people won’t be pardoned – Former Dep. AG

1 hour -

People want to see a president deliver to their satisfaction – Joyce Bawah

2 hours -

Presidents should have no business in pardoning people – Prof Abotsi

2 hours -

Samuel Addo Otoo pops up for Ashanti Regional Minister

2 hours -

Not every ministry needs a minister – Joyce Bawa

2 hours -

Police shouldn’t wait for President’s directive to investigate election-related deaths – Kwaku Asare

3 hours -

Mahama was intentional in repairing ties with neighbouring countries – Barker-Vormawor

3 hours -

Mahama decouples Youth and Sports Ministry, to create Sports and Recreation Ministry

3 hours -

Mahama’s open endorsement of Bagbin needless – Rabi Salifu

4 hours -

Police station torched as Ejura youth clash with officers

4 hours -

If Ibrahim Traoré goes civilian, it may be because of Mahama’s inauguration – Prof Abotsi

4 hours