Social enterprise as a concept is playing a key role in society. At the centre of social enterprise is the importance of entrepreneurship and innovation. Over a long period of time, social enterprise has been recognised by key stakeholders (e.g. United Nations, Private, Public and Third Sectors) as the mechanism for providing interconnectivity. Fundamentally, social enterprise is seen as a problem solver for some of the most social, economic, and environmental challenges that are encountered in today’s world (Oberoi et al., 2021; Halsall 2020; Oberoi et al., 2020).

The aim of this brief article is to provide an updated narrative on social enterprise within a Ghanaian context. Firstly, the article will provide a definition of social enterprise from a Ghanaian perspective, with a figure to explain this in a visionary way. Secondly, the authors explore the social inequalities that are faced by Ghanaian women and then discuss how entrepreneurship and innovation are key in tackling this underlying gender problem.

The authors of this article are currently undertaking a British Council-funded project focused on the increased culture of entrepreneurship and innovation within a higher education setting (British Council, 2022). For this project, the key emphasis of the research is to see how social enterprise can be better integrated into economic development in Ghana from a higher education policy perspective (Quaye et al., 2022; Quaye et al., 2021).

Defining Social Enterprise in the Context of Ghana

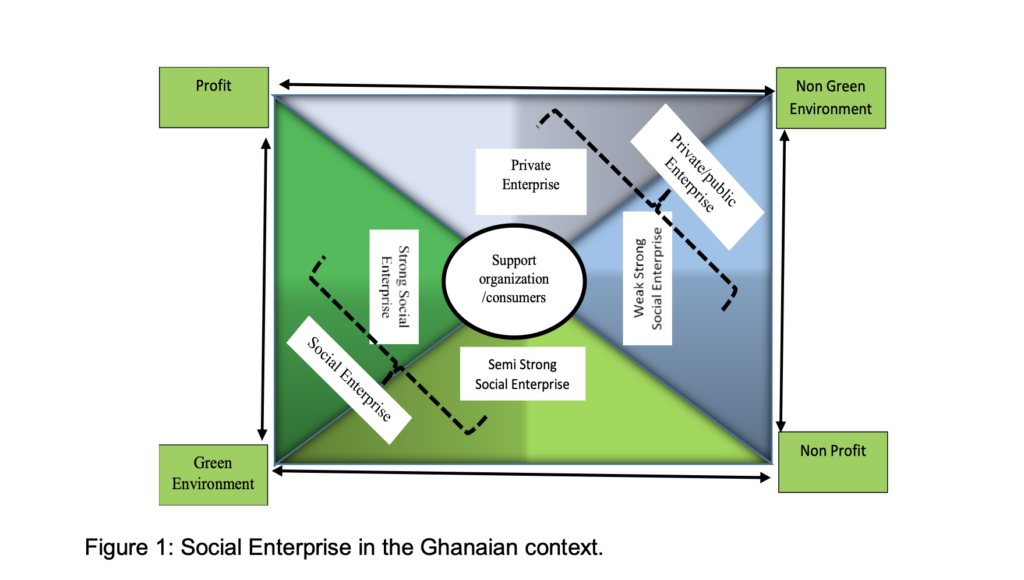

There is currently no formal definition of social enterprise in Ghana. The understanding of social enterprise varies from country to country, as do the names used to describe social enterprises. From the Ghanaian perspective, the main aim of social enterprises is to generate social value, and this is what sets them apart from other organisations. As illustrated in Figure 1, the Ghanaian context defines social enterprise and private enterprise by looking at the combination of profit levels and the level of environmental aptitude.

An enterprise that considers a high level of profit and also a high level of environmental aptness is considered a strong social enterprise. On the other hand, non-profit and non-environmentally suitable organisations are described as weak social enterprises. In the area of support organisations, few of them provide targeted support to social enterprises. Figure 1 below can also be used to classify support organisations into relative support for social enterprise. These support organisations cut across donor agencies, NGOs, government, and private enterprises.

In terms of social enterprise, as portrayed in Figure 1 above, it portrays that are little literature on enterprise that can be classified as a social enterprise since independence. There are, however, some social enterprises that have been operating in Ghana since 2014, but they are all small in size and operation. They may be referred to as weak social enterprises. This has been the case because there is no legal framework for their operations and direction; hence, it is very difficult to operate social enterprises in Ghana. A social enterprise, as portrayed in Figure 1, is at the formative stage in Ghana, since many stakeholders and government are not acquainted with the concept.

There are a growing number of support organisations playing a role in the development of the social enterprise ecosystem in Ghana, particularly in Accra. These range from business support organisations, focusing on small and growing businesses that achieve social impact (e.g., Growth Mosaic), to workspaces with convening and incubation support (e.g., iSpace), and incubators (e.g., Impact Hub Accra), as well as early-stage funding and support providers (e.g., Reach for Change) and long-standing more conventional NGO and SME support organisations (e.g., TechnoServe). Equally, the understanding and support for social enterprise is growing at high levels within government, but these initiatives are still not commonly seen amongst officials interacting with social enterprises on the ground. Education and agriculture are the most cited sectors in which Ghanaian social enterprises work, with education social enterprises being particularly dominant in Accra and agricultural social enterprises most common in the North.

Social enterprise is growing rapidly in Ghana, driven by a combination of international NGO projects and returning diaspora. A report from the British Council estimates that the number of social enterprises in Ghana could be as high as 26,000. While the concept of social enterprise is relatively new to Ghana, social-enterprise-type activity has a longer history. It is therefore very important for Ghana to define social enterprise, which would then serve as the basis for classification, legal and regulatory frameworks for Ghana.

Gender Issues in Social Enterprise

Women are given equal rights under the Constitution of Ghana; yet, disparities in education, employment, and health for women remain prevalent. Additionally, women have much less access to resources than men in Ghana do. Efforts to bring about gender equality continue to grow in Ghana, but Ghana continues to face considerable challenges in the area of gender equality.

According to the World Economic Forum, Ghana is ranked 117 out of 156 countries for gender equality in the ‘2021 Global Gender Gap Report’ (2021). Under the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection, the legal and policy framework for gender was developed and strengthened. Ghana now has a Domestic Violence Act (2006), a Gender Policy (2015), and an Affirmative Action/Gender Equality Bill (2016). This positive political framework is slowly creating change for women and girls in Ghana. Ghana is one of the few countries in the world where the start-up rate for businesses is the same for men and women. However, gender inequality remains a huge problem in Ghana, particularly in areas where traditional government structures are still strong. Women and girls in Ghana continue to face many problems and challenges encompassing: discrimination, unfair inheritance practices, sexual assault, domestic violence, and human trafficking. In the ‘Social Institutions and Gender Index 2014 Edition’, Ghana received the worst possible ratings for discrimination against women in social institutions, sexual harassment, and in restricted access to resources and assets. In education, women had on average six years of schooling in 2010, compared to eight years on average for men. In health, the adolescent fertility rate is still high with 57 births per 1000 adolescent girls, and in 2013, 37% of women had an unmet need for family planning. Furthermore, many other health problems fall disproportionately on the shoulders of women in Ghana. The ill effects of smoke from cooking, for example, are predominantly experienced by women and children.

While national laws in Ghana give equal rights of property ownership to men and women, the reality varies enormously among regions. The percentage of female landholders ranges from two % in the northern region to 50 % in the Ashanti region. In the Ashanti region, property is distributed according to a matrilineal system. In the North, women often lose the land they are farming to male relatives if their husbands die. Many women in Ghana have little financial independence and little access to credit; this restricts their opportunities to develop businesses, including social enterprises. In most Ghanaian families, household chores and raising children are the sole responsibility of women. This provides an additional barrier to employment or running a business compared with men. Prejudice is also a considerable barrier. Although the situation is improving slowly (credit to a combination of campaigns from WROs, and other social factors), men in Ghana frequently still view women as inferior.

Traditionally, women are seen as homemakers. This role includes marriage, child bearing and domestic chores. As a result, women and girls are often not encouraged to achieve academic or career success. In the workplace as well, women in leadership positions face the challenge of discomfort. Women with the same qualifications and experience as men are paid less than their male counterparts. There is also a strong gender divide in the workforce, with some roles viewed as feminine and others masculine. For example, administrative work, such as in secretarial roles, is typically seen as female, and so men are not hired for such positions, while engineering is seen as a job for men. There is often little provision for maternity leave, making it difficult for women to combine family and career.

Women also face discrimination in the job market, as many employers assume their domestic and familial responsibilities will be an additional burden to the company. In terms of country governance and politics, there are few women who are part of the country’s legislature. Currently, out of the 275 members of parliament, only 40 (14.55 %) are female. Despite legal protections, domestic violence is common. According to the latest ‘Demographic and Health Survey’ (2019), nearly 37 % of women had experienced physical violence, 17 % in the previous year. In the same survey, 20.6 % of women were reported to have experienced physical violence at the hands of their partners at some point in their lives, with 23 % having experienced violence by an intimate partner in the past year. Many women also experience sexual harassment, with women interviewed for this research reporting being turned down for jobs when they refused to have sex with their potential employer. The Gender Index gives Ghana the worst possible rating for sexual harassment. Social enterprise does not provide a solution to all the gender inequality in Ghana, but it is playing an increasing role in tackling some of these injustices.

Gendered employment disparities persist in Ghana. Although available statistics show that males’ employment rate (54.9%) is just slightly higher than that of females (53.4%), women are more likely to engage in vulnerable employment (females 71.3%, males 37.9%], and are less likely to work in paid employment, given that the proportion of males in paid employment is much higher (25.0%) compared to that of females (8.2%) (Ghana Statistical Service, 2017). Furthermore, there is inequality in the pay men and women receive. Men receive higher earnings than women, with men earning 61 Ghana Pesewas (GP) per hour on average, and women earning only 50GP. The average hourly earnings are 55GP (1.96 Ghana Cedis (GhC) = US$1 in 2012). Educational levels are also higher among men (67%) than women (46%) (Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO), 2012).

The British Council report (2015) found that social enterprise is playing a growing role in women’s empowerment through its impact on beneficiaries, entrepreneurs, employees and social norms in the following four ways:

Developing skills

Providing employment

Facilitating the economic empowerment of women

Giving women a voice in their community

Perhaps surprisingly, women social entrepreneurs are not primarily driven to social enterprise in order to earn an income. For women in Ghana, the primary motivation for setting up a social enterprise was to address a social or environmental concern, or to benefit their community.

Summary

This article provides an overview of the significance of social enterprise in Ghana. It acknowledges that the exact meaning of social enterprise is not apparent and highlights that the various ways the concept is utilised differ enormously. However, in the context of Ghana, social enterprise is perceived as a developmental tool for community groups and a creative response to solving economic, social, and environmental problems. Social goals are prioritised as opposed to business-like strategies, where emphasis is placed on social enterprise as an innovative method of creating and satisfying social values that lead to a positive social change. The goal of social enterprise in Ghana is extended to the marginalised and vulnerable people in the community. In view of this, gender inequalities are exposed and have continued to grow, holding back the efforts to level up gender equality. Social enterprise is characterised as having a role to play in empowering women and bridging the gender gap in Ghana. A project sponsored by the British Council is a suitable fit for integrating social and economic development in Ghana. This innovation project can be optimised by inculcating entrepreneurship in the higher education environment and cascading it into the community. It is the intention of this sponsored project to work collaboratively with higher education institutions in Ghana to promote social enterprise in disadvantaged communities. Further field studies aimed at achieving gender equality through social enterprise in Ghana need to be considered in the future.

References

British Council. (2022) Innovation for African Universities.

Weblink: https://www.britishcouncil.org/education/he-science/opportunities/innovation-african-universities. (Accessed 16th February 2022).

British Council. (2015) The State of Social Enterprise in Ghana. Weblink: www.britishcouncil.org/society/social-enterprise. (Accessed 9th February 2022).

Halsall, J. P., Oberoi, R. and Snowden, M. (2020) A New Era of Social Enterprise? A Global Viewpoint. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Economic Issues, Vol. 4(1), pp. 79-88. DOI: https://doi.org/10.32674/ijeei.v4i1.34.

Oberoi, R., Halsall, J. P. and Snowden, M. (2021) Reinventing Social Entrepreneurship Leadership in the COVID-19 Era: Engaging with the New Normal. Entrepreneurship Education, Vol. 4 (2), pp. 117-136. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41959-021-00051-x.

Oberoi, R., Halsall, J. P., Snowden, M. and Bhatia, R. (2020) The Public Policy Significance of Social Enterprise: A Case Study of India. Journal of Governance & Public Policy, Vol. 10(2), pp. 34-46. Weblink: https://www.ipeindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/IPE-JoGPP-Jul-Dec-2020-FINAL.pdf.

Quaye, J. N. A., Snowden, M., Winful, E. C., Halsall, J. P., Hyams-Ssekasi, D., and Opuni, F. F. (2022) Social Enterprise: The Quiet Solution to Ghana’s Unemployment Situation. Weblink: https://www.graphic.com.gh/business/business-news/social-enterprise-the-quiet-solution-to-ghana-s-unemployment-situation.html. (Accessed 16th February 2022).

World Economic Forum. (2021) Global Gender Gap Report. Weblink:

https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2021. (Accessed 16th February 2022).

About the Authors:

Michael Snowden is a Senior Lecturer in Mentoring Studies in the School of Human and Health Sciences at the University of Huddersfield, UK. His research interests lie in the fields of pedagogy, mentorship, social enterprise, curriculum enhancement, and learning. Michael is a regular speaker at national and international conferences concerned with the development of pedagogical strategies in various contexts.

Email: m.a.snowden@hud.ac.uk

Ernest Christian Winful is a professionally astute Senior Lecturer and a Certified Research Fellow with 19 years of experience in providing comprehensive, high-quality teaching. He has over 20 published articles and conference presentations to his credit. His research interest lie in efficiency, finance and economic inclusion.

Email: ewinful@atu.edu.gh

Jamie P. Halsall is a Reader in Social Sciences in the School of Human and Health Sciences at the University of Huddersfield, UK. His research interests include communities, globalisation, higher education, public and social policy. Currently, Jamie is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, a Chartered Geographer of the Royal Geographical Society, and was awarded Senior Fellowship of the Higher Education Academy in January 2017.

Email: j.p.halsall@hud.ac.uk

Elikem Chosniel Ocloo is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Marketing within the Faculty of Business, Accra Technical University, Ghana. He has special interest in current business trends in digitalisation and 4th industrial revolution concepts. His research areas include e-commerce/technology adoption, SMEs development, social enterprise, B2B marketing, health marketing, and social marketing. Elikem is an Associate Member of the Chartered Institute of Marketing, Ghana (CIMG).

Email: ceocloo@atu.edu.gh

Denis Hyams-Ssekasi is a Lecturer in Business and Management at the Institute of Management at the University of Bolton, UK. His research interests include social enterprises and entrepreneurship, intercultural communication, internationalization and high performance work systems. Denis is currently a member of the Institute for Small Business and Entrepreneurship as well as a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy.

Email:dh4@bolton.ac.uk

Emelia Ohene Afriyie is a Senior Lecturer in Accra Technical University and holds a Doctorate in Business Administration from the Centre of Advanced Study and Strategy, European Institute of Management Studies, France. She has a Masters of Philosophy in Leadership from the University of Professional Studies, a Masters of Business Administration in Entrepreneurship and Small Enterprise Development from Cape Coast University, and a Bachelors of Education in Secretarial Management Studies from the University of Education: Kumasi Campus. She is currently the Head of Department in Management and Public Administration at Accra Technical University.

Email: eoheneafriyie@atu.edu,gh

Frank Frimpong Opuni is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Marketing within the Faculty of Business at Accra Technical University, Ghana. He is also a PhD Candidate at the University of Bolton, UK. His research interests lie in the areas of social, digital and services marketing. He was admitted as a fellow of the Global Strategic Management Institute, Michigan in 2013 and is also an Associate Member of the Chartered Institute of Marketing, Ghana (ICAG).

Email: fofrimpong@atu.edu.gh

Kofi Opoku-Asante is a Lecturer in the Accounting and Finance department of Accra Technical University. His research areas include social enterprises, the social impact of public policies, individual social change actions, business financial structure, performance measurement in the service sector, and youth in ICT business. He is a member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants, Ghana (ICAG).

Email:kopoku-asante@atu.edu.gh

Josiah Nii Adu Quaye is an Assistant Lecturer in the Accounting and Finance Department at Accra Technical University, Ghana. His research interests lie in the fields of forensic accounting and auditing, finance, taxation, social policies, and social enterprise. He is a qualified accountant and a member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants, Ghana (ICAG).

Email: jnquaye@atu.edu.gh

Latest Stories

-

Borborbor deserves global recognition – Efadzinam Borborbor band

2 minutes -

Unannounced visits to health facilities way to go – Sammy Gyamfi touts Health Minister

17 minutes -

Cedi depreciates by about 4% to dollar so far in 2025 – World Bank

20 minutes -

Tamale Teaching Hospital CEO’s dismissal: The one who has prerogative to hire also has prerogative to fire- Sammy Gyamfi

23 minutes -

I will prioritise inclusive development, guided by Mahama’s vision – Anloga DCE

32 minutes -

It’s unacceptable to lose lives over lack of ventilators, but… – Egyapa Mercer scolds Health Minister over Tamale Hospital fracas

38 minutes -

‘You deserved it’ – Yaya Toure to Mikel Obi on 2013 CAF Footballer of the year award

46 minutes -

National Peace Ambassador advocates for unity and development at Dzita Easter festival

52 minutes -

30 out of 31 Council of State members agreed on ‘prima facie case’ against CJ – Sammy Gyamfi

58 minutes -

Torgbui Sri calls for action on sandbar blockade and coastal erosion in Anloga district

1 hour -

Akatsi South MCE embarks on institutional tour to strengthen public service delivery

2 hours -

Saudi Pro League side Al Nassr targets Ghana striker Antoine Semenyo

2 hours -

World Bank forecast a high inflation of 17.2% for Ghana in 2025

2 hours -

Ghana set to roll out chip-enabled passports from April 28

2 hours -

Mohammed Kudus linked to €100m Saudi move

2 hours