Hundreds of yellow stringy plastic mass scattered under trees where African pied crows perch has been a wonder to many Ghanaians.

With this and other questions begging to be answered, Luv FM's Emmanuel Kwasi Debrah investigates this phenomenon while exposing the consequences of some of Ghana's overlooked poor sanitation behaviours.

On the roof of a building at Asokore Mampong in the Ashanti Region of Ghana, an African pied crow (Corvus albus) can’t let go of a plastic bag it picked from an open bin just beside the house.

It then decides to bite off a small piece, and on the third piece, it’s interrupted by another crow which took almost half of the ‘delicacy’ to munch on.

"This behaviour is common with all other pied crows within the city irrespective of their location," an ecologist with the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Rev. Steven Akyeampong noted.

Crows' omni diet

The African pied crow is a black-and-white crow locally known in Ghana as ‘Anene’ or ‘Kwaakwaadebi’. It has glossy black head and neck interrupted by an area of white feathering from the shoulders down to the lower breast.

According to the Ghana Wildlife Society, the pied crow can be spotted in Ghana, Nigeria and some parts of Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. They are mostly found in all habitats except dry deserts and thick rainforests.

Crows are considered to be among the world’s most intelligent birds. Research has acknowledged their ability to distinguish humans by recognizing facial features.

Crows are omnivorous and they can eat almost anything including grains, fruits, plastics and insects among others.

The yellow ochre-looking plastic feasted on by the crows is waste from plastic used for packaging foods like rice and stew or gari and beans.

Normally in Ghana, the transparent polythene bag is used to wrap food followed by the black polythene bag, which is used to carry the food and at the same time concealing the package.

Indeed, crows' love for plastics was once reported by an article in wildnest.in, which captured a crow swallowing a plastic visually similar to the ones used for packaging foods in Ghana.

Pied crow's intelligence is also manifested in their ability to separate the clear plastic bag used for covering the food from the black polythene bag used to cover the entire package.

Yellow everywhere

About 6km away at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, pied crows can be found perching on tall Indian almond (Terminalia catapa) and acacia trees.

In a 2009 study published in the Journal of the Ghana Science Association, 102 nests were recorded of which 35 were inhabited by crows on the campus of KNUST.

Mean nest height for crow was 18m.

The researchers established that 89% of all nests were found in the developed areas of the KNUST campus, a situation the scientists attributed to availability of food source.

Indian almond was the most preferred host tree, accounting for approximately 29% of all nests.

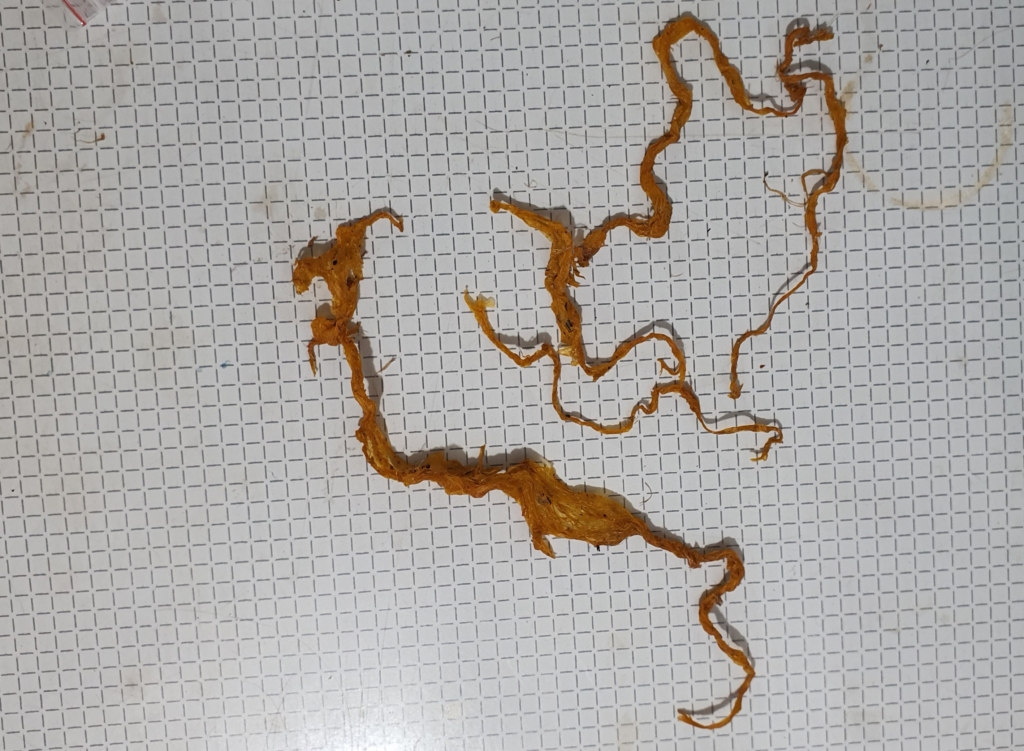

Beneath these trees are yellow tangled plastic mass spewed by the crows.

Since plastic is non-degradable, it's expected to stay in the digestive system which might lead to the death of these crows as asserted by an article published in wildnest.in. However, it seems the crows have managed to find a way to spew it.

Usually, the individual strands of the freshly vomited plastic mass is yellow ochre or lemon yellow and rope-like in structure. With time, they unwind and lose their pigment.

How much plastic can pied crows eat?

The plastic mass are of varied sizes. I therefore set out to collect seventeen (17) of these plastic mass from under 2 trees inhabited by pied crows within the KNUST campus.

First, I wanted to find out the type of plastic consumed by the pied crows, second, the number of plastics that constitute a mass, third the weight of each plastic strand and last, whether there are changes to the plastic.

The samples were then taken to the Chemistry Department of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology to ascertain the above.

Led by Dr Eugene Ansah, Ohaus Digital weighing scale was used to measure the weight of the plastic bag strands.

Of the 17 samples, we found out that a plastic mass contained a minimum of two (2), maximum of twenty three (23) plastic strands and an average of ten (10) strands.

For the weight, we found a minimum of 0.003 grams which is 10 times lighter than an average rain drop and the highest plastic weighing 2.911 grams or the combined weight of 11 rubber bands.

In order to find out about the type of plastic and whether the gut of the crow impacted some changes on the plastic, the following were undertaken:

Together with Dr. Ansah, we unwound and washed in distilled water to remove all debris from them. The samples were then treated with ethanol and air dried at room temperature prior to analysis.

We found that the plastic was indeed polyethylene. Again, the results showed that there were no changes to the plastic.

“The obtained spectrum was compared with the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) library on IR spectrum and the substance with closer resemblance was polyethylene,” Dr Ansah said.

Click here for the advanced report on the plastic samples.

Ghana’s waste disposal conundrum

According to a UNDP report, about 12,710 tonnes of solid waste is generated every day in Ghana. Sadly, only 10 percent is collected and properly disposed of. Plastic waste forms a large proportion of urban waste.

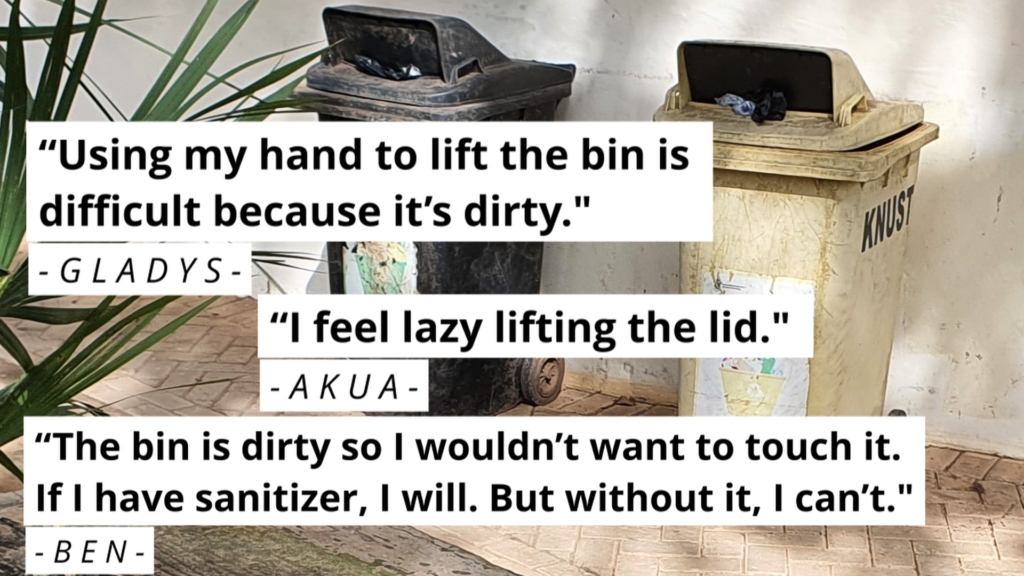

Interestingly, though many areas have bins with lids, they are sometimes slightly opened. And even when they’re closed, most of the waste are seen sticking out of the slit of the lid though the bin isn't full. Pied crows find it an easy grab.

But, what is the reason behind this peculiar behaviour of putting waste on the lid of bins? I therefore engaged ten (10) culprits to find out their motivation.

Out of this number, only one person cited laziness as reason for leaving the waste at the lid of the bin. The rest weren't enthused about the state of the bin.

"Using my hand to lift the bin is difficult because it's dirty," Gladys, a trader said.

Microplastics scare

Due to the large sizes of plastics, they can't be absorbed by the intestines and are therefore flushed out.

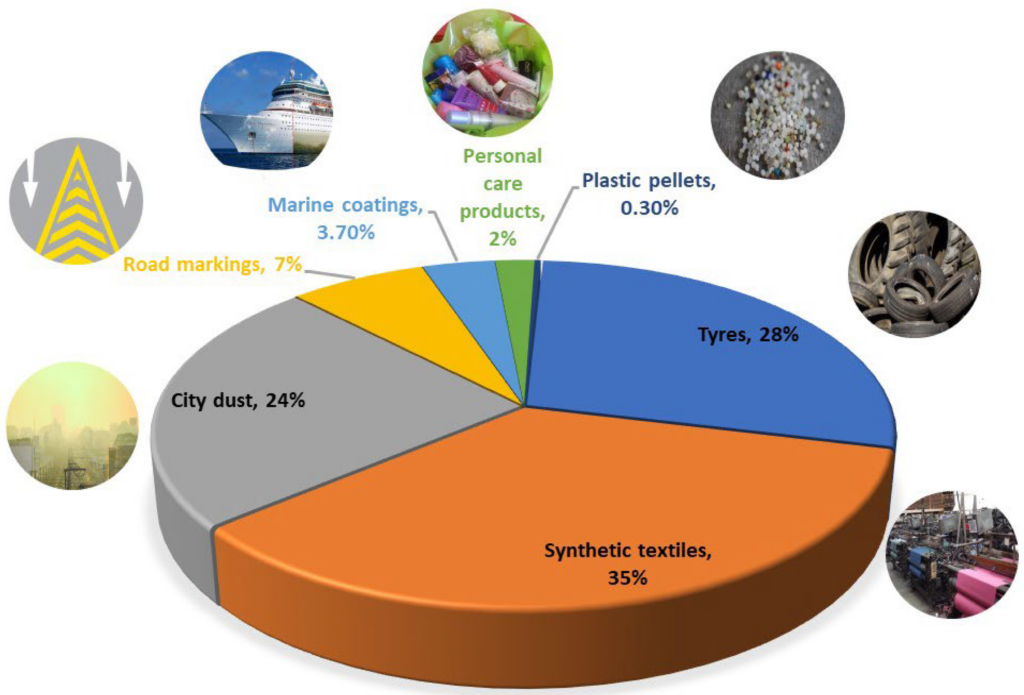

But, upon entering the environment, animals or humans, plastics break down into small particles, creating huge amounts of smaller plastic particles known as microplastics. Microplastics can be so small such that they can elude even modern microscopes! Did you think of your naked eyes?

Microplastics pollution has become one of the topical environmental issues globally.

Both humans and animals haven't been spared in the microplastic assault. In humans, microplastics have been fingered in DNA damage and inflammation. In animals like birds, it has been found to be damaging to vital organs like the kidney and liver. A study published in the Journal Environmental Pollution found a total of 1,197 pieces of plastics in the gastrointestinal tracts of birds examined.

Though processed cellulose lifted the trophy with 37%, polyethylene had a say with 16%.

The authors attributed to indirect and direct consumption of these plastics.

"It potentially could be due to a combination of direct intake of plastics and indirect consumption via trophic transfer," the report captured. The latter meaning, if a bird eats a fish or any animal containing microplastics, the bird acquires that animal's microplastics.

Also, a 2018 South African study which analysed faeces and feathers of seven African duck species found the presence of microplastics.

"African fresh water ecosystems and the biodiversity they support are under threat from micro-plastic contamination," the authors concluded.

Though my investigation found the polyethylene mass examined showed no changes in the chemical structure, it is possible some microplastics may have been left behind, which may negatively impact their health.

Indeed, the pied crows have revealed how poorly Ghanaian citizens have fared in terms of waste disposal practices particularly plastic waste.

Speaking with culprits of this poor waste disposal practice has called for innovative sanitation campaigns aimed at also tackling this peculiar waste disposal behaviour or better still as Ben, one of the culprits advocated, "the city authorities should adopt pedal waste bins" as a short-term measure.

Again, it has become important for African scientists to also investigate the extent of microplastics contamination in birds like the African pied crow and plastic-wrapped foods, to inform policy decisions geared towards keeping humans and animals safe from microplastics pollution.

Latest Stories

-

UPSA postpones Vice-Chancellor’s investiture amid alleged legal challenges

37 minutes -

China to build world’s largest hydropower dam in Tibet

53 minutes -

NPP Yendi chairman suspends 184 members for breach of constitution

1 hour -

Ghanaian media making strides despite challenges – Mercy Adjabeng commends progress

2 hours -

Ablakwa blows whistle on ADB’s $750K ‘Midnight Contract’ amid transition tensions

2 hours -

Elon Musk’s ‘social experiment on humanity’: How X evolved in 2024

2 hours -

At least 69 migrants dead after boat sank off Morocco on Dec. 19, Mali says

2 hours -

Telecel Ghana Foundation’s Healthfest impacts over 400 residents in Techiman

2 hours -

EPA issues alert over Harmattan induced air pollution

3 hours -

South Korea votes to impeach acting president Han Duck-soo

3 hours -

Supreme Court to hear NDC’s challenge against High Court-ordered election re-collation today

4 hours -

The Nigerian watch-lover lost in time

4 hours -

At least 10 killed after Nigerian military jet targeting bandits bomb civilians

4 hours -

Regional challenges cost Egypt around $7bn of Suez Canal revenues in 2024, Sisi says

4 hours -

Morocco proposes family law reforms to improve women’s rights

4 hours