Michel Platini has always left others to sweat the small stuff. From his prodigiously talented playing days to his smooth rise through the administrative ranks – via the France 98 organising committee, as Sepp Blatter’s right-hand man and then as the head of European football – his ascent has been insouciant and seemingly effortless.

Indulged and outrageously talented as a child growing up in the small town of Joeuf in north-eastern France, on the pitch he was able to use his sublime skills to escape any difficult corner. But it now seems that a lack of attention to detail and an intrinsic belief that he plays by different rules have emerged as his fatal flaws.

“When you have played football at the highest international level, everything in life seems easier afterwards,” Platini told Le Sport magazine in 1987, shortly after he retired following a glittering career in the stripes of Juventus and the blue of France. “I am very rarely mistaken. I work on instinct.”

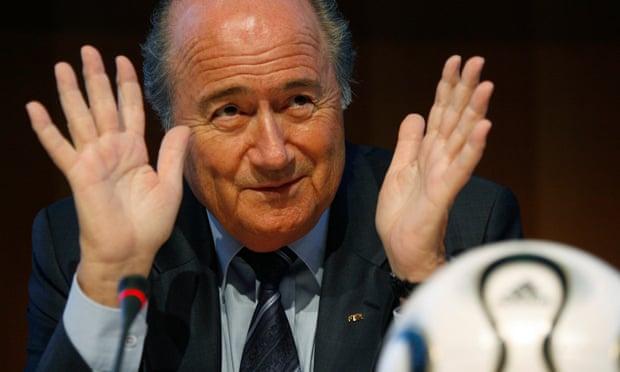

Little has changed since. But if Blatter’s downfall has been endlessly signposted as rumour has mounted upon rumour and dogged investigative journalism has produced a solid body of evidence until finally the FBI stepped in, then Platini’s has been more sudden – at least in the eyes of much of the footballing public.

As recently as late September he was a virtual shoo-in to replace Blatter, his one-time mentor turned bitter rival, as Fifa president.

That all changed when Michael Lauber, the Swiss attorney general, questioned Platini as someone “between a witness and an accused person” over an alleged “disloyal payment” – to use the term in Swiss law – that could bring him down.

France Football magazine has taken the lead in bravely questioning one of the country’s national icons as the seductive edifice of a playing great turned football administrator fighting the good fight for all that is pure has crumbled.

Everything we know about Platini suggests that he probably thought he was doing nothing wrong when he asked for that £1.35m payment – CHF2m – from his old mentor Blatter shortly before the 2011 Uefa congress in Paris.

Just as he saw nothing wrong with his son Laurent taking a job with a sportswear firm owned by the same Qatar sovereign wealth fund that owns Paris Saint-Germain 12 months after he voted for the tiny Gulf state to host the World Cup.

Just as he had no issue with Uefa commissioning his former son-in-law to write the theme music for the Europa League. Platini is so certain in his belief that his own motives are pure and incorruptible that he takes any suggestion that they may appear otherwise to the rest of the world as an affront to his character.

When asked last year whether he had pocketed one of the expensive watches handed to all Fifa executive committee members in São Paulo even as a storm over Fifa corruption raged outside the five-star hotel in which they were billeted, he joked that his mother had taught him it was rude to return a gift.

So it is no surprise that he also saw no problem with his now infamous meeting with the Qatari crown prince (now Emir) Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani and the then French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, nine days before the World Cup vote in December 2010.

In the air were various major trade deals, including a contract to sell Airbus planes to Qatar Air, and a prospective deal for QSI to buy PSG.

Although Platini has admitted that he initially leaned towards voting for the USA, he has repeatedly insisted that his vote to take the World Cup to Qatar was his personal choice alone.

“I knew Sarkozy wanted the people from Qatar to buy PSG,” Platini later told the Guardian. “I understood that Sarkozy supported the candidature of Qatar. But he never asked me, or to vote for Russia [for the 2018 World Cup]. He knows my personality. I always vote for what is good for football. Not for myself, not for France.”

Platini later described the World Cup vote as though it was an irritation to be swatted aside. “Everybody know my vote and nobody disturb me and I have no problem of corruption … finished. You can imagine, when you have 15 bids … we come to see you, Mr Putin wants to see you, Mr Cameron want to see you, the Queen wants to see you; OK. I say don’t break me the balls. Stop,” he later told the Daily Mail.

“Is why always I want to announce my vote, then I am free and nobody comes to disturb me. All your friends come. Stop. Let me in peace.”

As Blatter as been endlessly keen to point out since, it was the European vote that did most to help Qatar to victory. Spain’s Ángel María Villar Llona (widely believed to have concluded a vote-swapping pact with Qatar, though both sides deny collusion) and Cyprus’s Marios Lefkaritis (alleged to have benefited from a land deal with the Qataris, which the Cypriot denies influenced his vote) were also among those backing its bid.

In January 2011, during a lunch break in the midst of a mind-numbing presentation to the press on how financial fair play would work, Platini would make the case to a gaggle of reporters that the tournament should be played in the winter and spread across the Gulf. So just a month after voting for Qatar, he was advocating a wholly different tournament to the one he had backed. As ever, he made it sound as though it was the most natural thing in the world. Later that year, Sarkozy would stand on a conference platform in Doha and argue forcefully for the World Cup to shift to winter.

“Who will remember the words in 12 years?” said Platini, relaxed over lunch in the heart of his Uefa stronghold. “In 12 years, everybody will be happy to have a very well-organised World Cup and not remember what’s happened before. When I organised the World Cup in France, we did [things] differently from what we proposed in the bid.”

It has been claimed that it was the 1998 World Cup in France, forever bathed in soft focus thanks to the victory of the hosts, that cemented Platini’s bonds with Blatter.

In his book How They Stole the Game, David Yallop details the extent to which access to a ready supply of tickets for the France 98 World Cup helped Blatter cement key relationships and woo voters from around the world.

Down the decades, the wheels of Fifa’s grotesque gravy train have been oiled by World Cup tickets, TV rights deals and positions on endless committees that come with perks and per diems attached.

After Platini helped Blatter defeat Lennart Johansson, the Uefa president, in Fifa’s 1998 presidential election, the Frenchman took up a position as a paid adviser to the Swiss. (Blatter would later help Platini depose Johansson at Uefa in 2007.) It is that contract, or rather the lack of one for the “oral agreement” that guaranteed another £1.35m, that led to his current travails.

In 2002 Platini ascended to the Fifa executive committee and since then has been party to its freewheeling soap opera of personal battles, side deals and petty politicking.

Fast forward to the 2011 Uefa congress in Paris and Mohamed Bin Hammam, energised by his part in Qatar’s World Cup bid victory, was seeking support for his nascent bid to topple Blatter as Fifa president. It was then that Platini requested his missing £1.35m. Shortly afterwards, he stood on the dias and – after thanking his members for backing his re-election as Uefa president – welcomed the fact there were two candidates running for the Fifa role.

It is understood that privately he had already agreed to back Blatter. In addition, Fifa gave its approval for Uefa to sell the TV rights to World Cup qualifiers as part of a four-year package, a scheme that led to Platini being lauded by the smaller members of the European confederation for looking out for their interests. Also in the mix was a tacit agreement that Blatter would stand down in 2015 and make his fourth term his last.

It was Blatter’s decision to renege on that agreement that prompted Platini’s fury four years later and led Uefa to back Prince Ali, the Jordanian royal who is standing for the presidency again but has also since fallen out with the Frenchman.

None of which is to say that Uefa under Platini has not done some good things. A capable cadre of executives, led by the general secretary, Gianni Infantino, has kept the show on the road while Platini has at least talked a good game over worthy issues such as match fixing and the scourge of third party ownership on fair competition.

Argument will continue to rage over whether Platini’s pet financial fair play project succeeded in stemming the flow of red ink across Europe (as its proponents claim) or whether its subsequent watering down was tacit acceptance that it was the wrong answer to the right question (as his critics claim).

More than ever, Platini has had to walk the line between keeping the biggest European clubs, forever on the brink of threatening a breakaway, from leaving the fold by promising them ever greater shares of cash from the Champions League while maintaining his image as a footballing romantic who also wants to help the little guys.

Given the extent to which the Champions League has locked in the natural order through its revenue model, many argue the balance has tipped too far towards the former.

Reaffirmed as president in 2011 at Uefa’s congress in Paris and then again four years later in Vienna just days before the dramatic dawn raids that signalled the beginning of the endgame for Blatter and Fifa, Platini has in some ways come to mirror the man who was once his mentor and became a bitter rival.

It is not for nothing that his South Korean rival Chung Mong-joon, himself now banned for six years, reached for the taunt “son of Blatter” when he wanted to wound Platini.

As Platini consolidated his power base in Nyon so he became both more erratic and increasingly autocratic in his ways. Uefa insiders describe a Tudor-style court in which various factions would compete for the ear of the president. Often, they say, a decree would come down from the presidential office that had to be enacted in haste by those below.

Some of Platini’s hunches have paid off, as he has sought to consolidate and expand Uefa’s power and sphere of influence. The Champions League remains a supremely successful sporting competition. In the face of scepticism, expanding the European Championship to 24 teams looks like a qualified success.

Even the vaguely bonkers plan to spread the 2020 tournament around Europe has won over many critics. Yet others – his refusal to countenance goalline technology, his failure to deal with deep-seated issues in Greece and Turkey, his reluctance to check the power of the biggest clubs – reflect badly on his laissez-faire style.

A small vignette played out at Stamford Bridge in October was as good an illustration as any of Platini’s Uefa. At the self-aggrandising Leaders in Sport Business conference, some of the Uefa administrators and number crunchers who had wrestled with the introduction of financial fair play were reeling off statistics and explaining complex models to justify its introduction.

Meanwhile, Platini’s office was reeling off statements as he fought for his political life and his public reputation in the wake of the Fifa ethics committee’s 90-day ban.

Uefa, based in Nyon on the shores of Lake Geneva four hours from the madhouse of Fifa HQ in Zurich, gives every impression of being a far more sane and stable beast than its cartoonishly chaotic sibling. Yet there are those within the Fifa administration who quietly point to the fact that Uefa does not always practise what it preaches when it comes to good governance.

It does not have term limits, for example, and Platini was recently re-elected for his third four-year stint. Nor does it have an independent ethics committee or transparency on remuneration.

Blatter, Platini and the Fifa secretary general, Jérôme Valcke – all suspended on the same day by the suddenly invigorated Fifa ethics committee – go back years in the byzantine power struggles of global football. It is clear that the blame game between these three men has played a key role in the downfall of the trio, locked as they appear to be in a reputational death spiral. The suspicion that Blatter has resolved to take Platini down with him is hard to dispel.

In an interview shortly after his suspension, Platini likened himself to Icarus. In 2016 he had imagined himself attending the European Championship in his native France, 32 years after he won the tournament as a player, as Fifa president and master of all he surveyed. Instead he has crashed to earth in the most dramatic way possible.

-

Follow Joy Sports on Twitter: @Joy997FM. Our hashtag is #JoySports

Latest Stories

-

GSTEP 2025 Challenge: Organisers seek to support gov’t efforts to tackle youth unemployment

1 minute -

Apaak assures of efforts to avert SHS food shortages as gov’t engages CHASS, ministry on Monday

25 minutes -

Invasion of state institutions: A result of mistrust in Akufo-Addo’s gov’t ?

41 minutes -

Navigating Narratives: The divergent paths of Western and Ghanaian media

53 minutes -

Akufo-Addo consulted Council of State; it was decided the people won’t be pardoned – Former Dep. AG

54 minutes -

People want to see a president deliver to their satisfaction – Joyce Bawah

2 hours -

Presidents should have no business in pardoning people – Prof Abotsi

2 hours -

Samuel Addo Otoo pops up for Ashanti Regional Minister

2 hours -

Not every ministry needs a minister – Joyce Bawa

2 hours -

Police shouldn’t wait for President’s directive to investigate election-related deaths – Kwaku Asare

3 hours -

Mahama was intentional in repairing ties with neighbouring countries – Barker-Vormawor

3 hours -

Mahama decouples Youth and Sports Ministry, to create Sports and Recreation Ministry

3 hours -

Mahama’s open endorsement of Bagbin needless – Rabi Salifu

3 hours -

Police station torched as Ejura youth clash with officers

4 hours -

If Ibrahim Traoré goes civilian, it may be because of Mahama’s inauguration – Prof Abotsi

4 hours