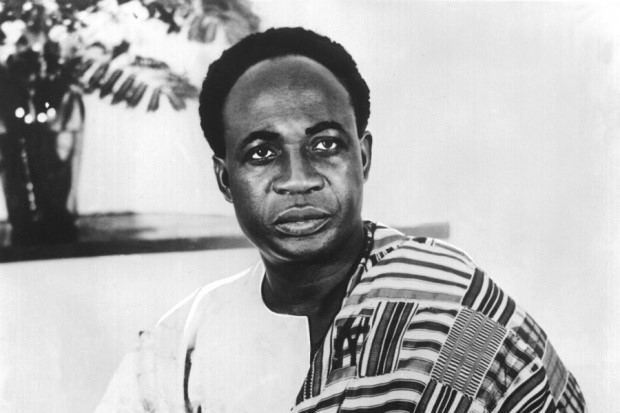

In 1945, Kwame Nkrumah envisioned a secret society that would provide the raison d’être for the emancipation of Africa.

He carefully observed, from afar, personalities who demonstrated the valour, discipline and intellect needed for a revolutionary struggle. One of the most remarkable qualities of Kwame Nkrumah was his superior ability to identify talent and form strategic alliances.

Nkrumah coordinated anti-imperialist activities from the headquarters of the West African National Secretariat, where he served as Secretary, located at 94 Gray’s Inn Road, London, United Kingdom.

He frequently voyaged to Paris where he met African members of the French Assembly, such as Léopold Sédar Senghor and Félix Houphouët-Boigny, and held pivotal consultations about the establishment of a Union of African Socialist Republics.

Nkrumah wasn’t encouraged by the reactions he received. It was clear that African members of the French Assembly, although arguably Pan-Africanist, weren’t committed to a radical political scheme aimed at the absolute decolonization of Africa. But Nkrumah still made some progress.

The conversations yielded some admirable results. A West African National Congress was scheduled for October, 1948 to assemble all Pan-African oriented political organizations and movements across the African continent in Lagos. Unfortunately, the conference never happened.

Nkrumah turned his attention to print press. He managed a monthly newspaper called ‘The New African’, with the motto: ‘For Unity and Absolute Independence'. The first issue, subtitled, 'The Voice of the Awakened African' was published in March, 1946.

The New African was an effective propaganda channel recognized for its unique perspective on the global political order after the Second World War. It quickly gained a wide readership. Nkrumah wasn’t driven by profit and didn’t structure The New African as a sustainable business venture. He was primarily concerned with its circulation and influence on public opinion. The newspaper lacked sufficient financial investment and soon collapsed.

Nkrumah subsequently pondered over the idea of a secret society and felt it had become necessary to institute one. This mysterious fraternity of non-conformists became known as ‘The Circle’.

The society prided itself on three principles: service, sacrifice and suffering. Its membership was largely drawn from scholars that met regularly at the West African National Secretariat. Members identified each other by a unique grip.

They held several discourses that were recorded in a document known as ‘The Circle’. This doctrine prepared members for revolutionary work, as a profession, across the African continent. It was difficult to gain admission into The Circle. The society was exclusively reserved for exceptionally conscious people.

Members swore an oath of unconditional loyalty to one another; to the endless pursuit of its stated aims and aspirations; and to never divulge its secrets. This oath included the mandatory acceptance of Kwame Nkrumah as leader.

The Circle congregated religiously and strategized. Its members were required to fast, from sunrise to sunset, on the 21st day of each month, assemble and meditate on the values that shaped the society.

It centred its operation on two core values: the ability to organize, as a mass-based socialist political organization, workers and peasants; and the need for Africa to unite.

The society encouraged its rank and file to infiltrate influential organizations, secure important positions and subtly infuse such organizations with the spirit of African unity.

The Circle planned to lead a series of non-violent well-coordinated strikes, boycotts and other forms of civil disobedience. It accepted that violence would be a last resort. The Circle never thought of decolonization as a feat that could be attained through negotiation; it was regarded as an arduous task that required a militant struggle. Members committed themselves to missions, regardless of the risks involved, in furtherance of African Unity.

The society kept its dialogue discreet; it relied on face-to-face contact, couriers and messengers for communications. The conventional methods of communication, such as letters, telegrams, telephones and cables were only used to book appointments. It forbade discussions about its inner-workings in public spaces.

The Circle disintegrated towards the end of 1947 after Nkrumah returned to the Gold Coast to serve as General Secretary of the United Gold Coast Convention.

The grand ideal behind the establishment of The Circle was to expand its territorial presence and gradually transform into a fully-fledged political organization, representative of West Africa, which would administer a Union of African Socialist Republics.

***

The author, V. L. K. Djokoto is an Adviser at D. K. T. Djokoto & Co and a Columnist passionate about history and politics.

Twitter/Instagram – @VLKDjokoto

Latest Stories

-

‘This is not Mahama’s tone’ – Senyo Hosi criticises ‘showmanship’ in attempted Ntim Fordjour’s arrest

8 minutes -

‘No opulence, no business-class tickets’ – Prof Gyampo criticises wasteful entitlement in public office

26 minutes -

Africa urged to stop blaming the West, focus on writing its own narrative

40 minutes -

‘Government vehicles must only be used for government business’ – Prof Gyampo rejects CEO privilege amid austerity drive

43 minutes -

Africa needs collective voice to fight Trump’s tariffs – Former Egypt’s Assistant Foreign Affairs Minister

56 minutes -

Bayindir’s failed Man Utd audition offers Onana dilemma

1 hour -

7 suspected illegal miners arraigned over Black Volta pollution in Wa West

1 hour -

Prof. Gyampo ushers in new era of austerity at Ghana Shippers Authority

1 hour -

Police gun down 4 suspected robbers in shootout on Bekwai-Fomena Highway

1 hour -

‘You don’t grandstand with Ghana’s image, that’s not being well-meaning citizen’ – Susan Adu-Amankwah

2 hours -

‘We are profiled as Ghanaians, not NDC or NPP’ – Susan Adu-Amankwah on suspicious flights

3 hours -

South Africa poised to re-open inquest into Nobel laureate’s death

3 hours -

Tanzania’s main opposition party banned from election

4 hours -

Nigerian bandit kingpin and 100 followers killed

4 hours -

Tariffs on imported semiconductor chips coming soon, Trump says

4 hours