Andy Ruiz Jr's mum blows a kiss to her son. He has just become a world champion and declared their struggles over.

Ruiz's trainer Manny Robles is sobbing, pointing to the heavens and praising the guidance of a dad he lost 12 years ago.

This is the dream.

A short walk away, in his Madison Square Garden dressing room, Anthony Joshua is told by his father that he must "go back to the drawing board".

Joshua's best friend, David Ghansa, wipes away tears.

This is the nightmare.

The week of the first Joshua v Ruiz fight had started with the laid-back Mexican outsider spitting off the rooftop terrace of a Manhattan building while waiting for an interview to begin.

That carefree attitude would prove his greatest asset in the days that followed, as the masses wrote him off.

Two weeks later, he was on his best behaviour, sitting alongside the president of Mexico, lauded as a national hero.

The night that gave him such status - as he humbled the undefeated Joshua - was one of shock and panic.

Here, in the week before the pair meet in a much-anticipated rematch, BBC Sport takes you behind the scenes of 1 June, with the help of some of those involved.

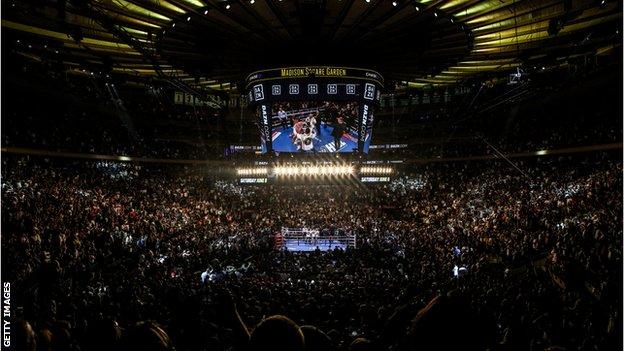

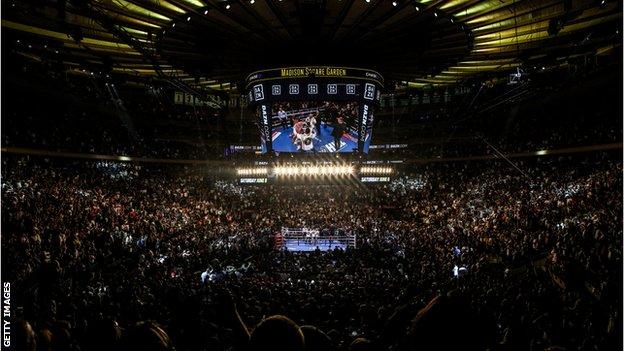

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- It's about 6:30pm in New York. Liverpool have just won football's Champions League in an all-English final. But their triumph will be knocked off top spot on the biggest sports websites within hours because of drama few can yet see coming.

Ruiz's name isn't even on some of the tickets held by fans queuing outside Madison Square Garden because he is a late stand-in to replace Joshua's original opponent, Jarrell Miller.

Joshua's statuesque frame is splashed across the billboards dominating the side of the arena. The Briton models a designer T-shirt.

Twenty-four hours earlier, by way of contrast, some people with money to make from the fight hoped the rotund Ruiz would keep his shirt on for the weigh-in. This is, after all, pay-per-view and some extra fat does little to convince punters of a competitive bout.

As the fight nears, the underdog prays in his dressing room. After entering the ring, he waits. Then Joshua makes his ring-walk. Before the fans in the arena can see him, he reminds himself of key instructions, saying: "Base, head movement and throwing calmly."

It's about 6:30pm in New York. Liverpool have just won football's Champions League in an all-English final. But their triumph will be knocked off top spot on the biggest sports websites within hours because of drama few can yet see coming.

Ruiz's name isn't even on some of the tickets held by fans queuing outside Madison Square Garden because he is a late stand-in to replace Joshua's original opponent, Jarrell Miller.

Joshua's statuesque frame is splashed across the billboards dominating the side of the arena. The Briton models a designer T-shirt.

Twenty-four hours earlier, by way of contrast, some people with money to make from the fight hoped the rotund Ruiz would keep his shirt on for the weigh-in. This is, after all, pay-per-view and some extra fat does little to convince punters of a competitive bout.

As the fight nears, the underdog prays in his dressing room. After entering the ring, he waits. Then Joshua makes his ring-walk. Before the fans in the arena can see him, he reminds himself of key instructions, saying: "Base, head movement and throwing calmly."

Joshua, now 30, was making his US debut at a venue often dubbed the 'Mecca of boxing'

Backstage, Callum Smith is being drug-tested after retaining his world title in three rounds. "All the testers were watching the Joshua fight on the TV and joking, saying: 'I think this one will be over quicker than your fight,'" he tells BBC Sport.

The testers may be on to something because Ruiz is swiftly floored, only to rise and drop Joshua twice by the end of round three.

"If you hit him you will slow him right down," Joshua is told by his trainer Rob McCracken.

In the opposite corner, seconds before round seven, Robles tells Ruiz: "You know you got him hurt now, so start going for the head."

British entertainer James Corden is open-mouthed at ringside. He intermittently shouts "come on AJ" in spurts, but for the most part, he is frozen, like most around him.

David Haye cannot sit down, much to the frustration of the reporter sitting behind him. As the drama unfolds, the former world heavyweight champion is the only man rising and falling more frequently than his humbled compatriot in the ring.

A third and fourth knockdown come in the seventh. Every time Joshua hits the canvas photographers lift cameras next to the ring, some within jabbing distance of his head. He is exposed and isolated as millions watch an iconic shock play out.

"I felt numb really," promoter Eddie Hearn tells BBC Sport. "I've seen so much in boxing - injuries, tragedy, ups and downs. You can become numb to the drama, but there was a little bit of disbelief."

Joshua, beaten, is on one knee in the corner of the ring. He has a towel draped over his head. His long-term manager Freddie Cunningham is standing over him with concern etched on his face.

"You can't have a mentality where you prepare for that, so everyone is kind of dealing with it at that current time," says Cunningham.

"Forget about sport. Seeing someone you know well not looking at 100%, there is huge concern. It is a friendship and that kicks in straight away."

In Cunningham's words, "things seem to move faster in an arena than a stadium" - and the fight and its aftermath are frenetic.

Rumours hit ringside, ranging from Joshua being unwell to him collapsing backstage earlier in the night. His team will later deny them. His dad is in the ring berating Hearn.

Joshua exits. His acceptance of defeat will be criticised. He can do nothing right on this night.

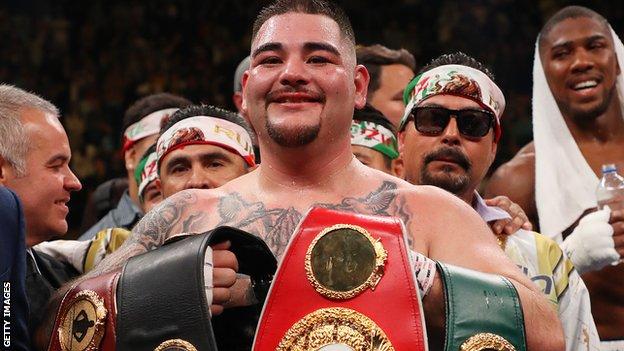

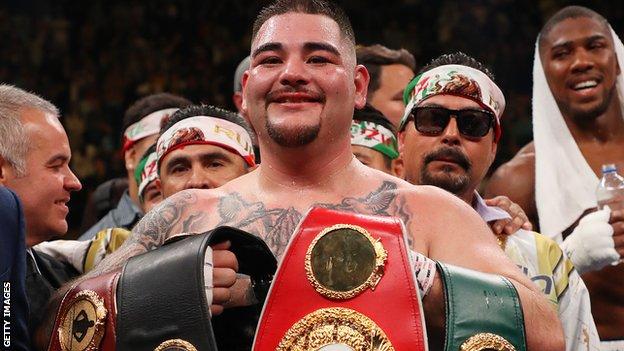

Ruiz leaves the ring. Draped in belts, he walks out of the arena and through corridors where he is yelled at: "You shocked the world champ. The whole world loves you baby." He can do nothing wrong on this night.

The hopeless, overweight, smiling underdog - nicknamed "destroyer" because he broke things as a child - was a wrecking ball.

There is media panic. On a boxing night for the ages, every word of reaction has become precious.

Joshua, now 30, was making his US debut at a venue often dubbed the 'Mecca of boxing'

Backstage, Callum Smith is being drug-tested after retaining his world title in three rounds. "All the testers were watching the Joshua fight on the TV and joking, saying: 'I think this one will be over quicker than your fight,'" he tells BBC Sport.

The testers may be on to something because Ruiz is swiftly floored, only to rise and drop Joshua twice by the end of round three.

"If you hit him you will slow him right down," Joshua is told by his trainer Rob McCracken.

In the opposite corner, seconds before round seven, Robles tells Ruiz: "You know you got him hurt now, so start going for the head."

British entertainer James Corden is open-mouthed at ringside. He intermittently shouts "come on AJ" in spurts, but for the most part, he is frozen, like most around him.

David Haye cannot sit down, much to the frustration of the reporter sitting behind him. As the drama unfolds, the former world heavyweight champion is the only man rising and falling more frequently than his humbled compatriot in the ring.

A third and fourth knockdown come in the seventh. Every time Joshua hits the canvas photographers lift cameras next to the ring, some within jabbing distance of his head. He is exposed and isolated as millions watch an iconic shock play out.

"I felt numb really," promoter Eddie Hearn tells BBC Sport. "I've seen so much in boxing - injuries, tragedy, ups and downs. You can become numb to the drama, but there was a little bit of disbelief."

Joshua, beaten, is on one knee in the corner of the ring. He has a towel draped over his head. His long-term manager Freddie Cunningham is standing over him with concern etched on his face.

"You can't have a mentality where you prepare for that, so everyone is kind of dealing with it at that current time," says Cunningham.

"Forget about sport. Seeing someone you know well not looking at 100%, there is huge concern. It is a friendship and that kicks in straight away."

In Cunningham's words, "things seem to move faster in an arena than a stadium" - and the fight and its aftermath are frenetic.

Rumours hit ringside, ranging from Joshua being unwell to him collapsing backstage earlier in the night. His team will later deny them. His dad is in the ring berating Hearn.

Joshua exits. His acceptance of defeat will be criticised. He can do nothing right on this night.

Ruiz leaves the ring. Draped in belts, he walks out of the arena and through corridors where he is yelled at: "You shocked the world champ. The whole world loves you baby." He can do nothing wrong on this night.

The hopeless, overweight, smiling underdog - nicknamed "destroyer" because he broke things as a child - was a wrecking ball.

There is media panic. On a boxing night for the ages, every word of reaction has become precious.

Ruiz, who turned 30 in September, was born in Imperial, California

Britain's Smith is holding his news conference as the world's media flood into the room, fresh from the Joshua drama a few metres away. Cameras are being erected at speed, people are on phones, others are asking where Joshua is and word breaks he is having a concussion test.

"I felt awkward. I remember thinking that there is no-one in here who cares about what I am about to say," recalls Smith. "It felt like someone had died in there at times."

Ruiz enters to applause and cheering from some. One man is shouting: "The champ is here." Hearn, one of the sport's smoothest talkers, speaks on stage but still looks a touch dazed. His friends back in the UK are texting him asking if he is OK.

"You have to stay focused. I had a job to do," he remembers.

Ruiz tells his mother he loves her, prompting her blown kiss.

His trainer, a man who says he arrived in the US as an illegal immigrant as a child, is breaking down. He lost his father, job and home in 2007. Questions about his boxing-enthusiast dad reduce him to tears. Triumph reminds him of the wife that stuck with him through it all.

Joshua is in the dressing room used by the New York Knicks. BBC commentator Mike Costello is outside one door, his Radio 5 Live sidekick Steve Bunce is at the other exit. Joshua is pinned in because his post-fight interview is the one everyone desperately wants to hear.

"It had gone midnight and I was there for well over an hour, maybe close to two," says Costello.

"I could see directly down the corridor leading to the arena, where staff were de-rigging the ringside furniture in readiness for a Billy Joel concert the next evening. 'Life goes on,' I thought, even though it felt to many of us as though the world had stopped turning."

Joshua, flanked by his team, emerges. Bunce is primed.

"I was by the service elevator, the one that can hold golf carts ferrying VIPs and also fallen world champions and their entourages of 30 or so people," says Bunce.

"The place had fallen quiet. At one point the lift arrived, doors opened and Ruiz and his people emerged, laughing and smiling. It soon went silent again for a very long time.

"AJ was first out of the back door of the changing room, paused for a moment and then smiled when he saw me. I asked him the first questions as we all filled the lift."

Back at the news conference, Ruiz departs and media are told Joshua will not be attending. Journalists wait and are told again and again. Eventually, large numbers begin to leave.

"AJ was concussed and the doctor said to him: 'Don't do a news conference,'" says Hearn. "When he got showered and I saw him, he said we should do it. I was telling him to leave it."

Through texts and social media, a handful of the departed reporters hear Joshua will turn up. They race back but security insists no-one re-enters the famous arena. After lengthy explanation, they get in to find a defiant former champion.

Joshua describes the night as "a blip", while some of his team sit close by, their heads in their hands. Some lie flat on their backs and stare at the ceiling.

"It was a difficult night. As difficult as it can get," said his trainer Robert McCracken.

Reporters set up cameras outside Madison Square Garden and shoot live into breakfast shows back in the UK. Bunce stays up all night to talk boxing to countless outlets.

Hearn goes back to his hotel and cannot sleep all night, while Joshua and his team return to the Manhattan house they have rented.

He stays in there for the next three days.

"You're either in the house or it's mental outside," recalls manager Cunningham. "You're kind of stuck. You had the house to kind of process it all.

"But the people who have always been there were there. It was deflating but there was a feeling like nothing changes, so how do we help?"

Highlights play out on US breakfast shows. The chubby man beat the Adonis. This was a tale to inspire those who have never even watched boxing. Joshua, on his US debut, had been laid bare - and it was brutal.

"I remember seeing him maybe two weeks after and you could tell he wasn't in a good place," adds Hearn.

"It took him a long while to get in a good frame of mind but we made our decision on a rematch quickly."

As Ruiz, Mexico's first heavyweight world champion, met the country's president and appeared on late-night US talk shows, those on the opposite side were beginning to feel the pain.

"I didn't realise how hard it hit me mentally, emotionally and even physically," says Hearn.

"The week after I had a Gennady Golovkin fight week, then I had my 40th birthday in Ibiza with friends and was still gutted. A week after that I felt utterly drained, run down and mentally low."

Ruiz, as he did throughout the biggest fight week of his life, was still smiling as he paraded on the back of a convertible Rolls Royce through his city of residence in California.

Weeks earlier he had stood on that New York roof-top in baggy jeans, trainers and an ill-fitting blazer, with his hands in his pockets and the air of a man who was simply grateful to be asked questions.

He was not treated like a champion. He did not look like a champion. And yet, six days on - despite a widespread lack of belief - he was one.

He had the night of his life. It was one the sporting world will never forget.

Ruiz, who turned 30 in September, was born in Imperial, California

Britain's Smith is holding his news conference as the world's media flood into the room, fresh from the Joshua drama a few metres away. Cameras are being erected at speed, people are on phones, others are asking where Joshua is and word breaks he is having a concussion test.

"I felt awkward. I remember thinking that there is no-one in here who cares about what I am about to say," recalls Smith. "It felt like someone had died in there at times."

Ruiz enters to applause and cheering from some. One man is shouting: "The champ is here." Hearn, one of the sport's smoothest talkers, speaks on stage but still looks a touch dazed. His friends back in the UK are texting him asking if he is OK.

"You have to stay focused. I had a job to do," he remembers.

Ruiz tells his mother he loves her, prompting her blown kiss.

His trainer, a man who says he arrived in the US as an illegal immigrant as a child, is breaking down. He lost his father, job and home in 2007. Questions about his boxing-enthusiast dad reduce him to tears. Triumph reminds him of the wife that stuck with him through it all.

Joshua is in the dressing room used by the New York Knicks. BBC commentator Mike Costello is outside one door, his Radio 5 Live sidekick Steve Bunce is at the other exit. Joshua is pinned in because his post-fight interview is the one everyone desperately wants to hear.

"It had gone midnight and I was there for well over an hour, maybe close to two," says Costello.

"I could see directly down the corridor leading to the arena, where staff were de-rigging the ringside furniture in readiness for a Billy Joel concert the next evening. 'Life goes on,' I thought, even though it felt to many of us as though the world had stopped turning."

Joshua, flanked by his team, emerges. Bunce is primed.

"I was by the service elevator, the one that can hold golf carts ferrying VIPs and also fallen world champions and their entourages of 30 or so people," says Bunce.

"The place had fallen quiet. At one point the lift arrived, doors opened and Ruiz and his people emerged, laughing and smiling. It soon went silent again for a very long time.

"AJ was first out of the back door of the changing room, paused for a moment and then smiled when he saw me. I asked him the first questions as we all filled the lift."

Back at the news conference, Ruiz departs and media are told Joshua will not be attending. Journalists wait and are told again and again. Eventually, large numbers begin to leave.

"AJ was concussed and the doctor said to him: 'Don't do a news conference,'" says Hearn. "When he got showered and I saw him, he said we should do it. I was telling him to leave it."

Through texts and social media, a handful of the departed reporters hear Joshua will turn up. They race back but security insists no-one re-enters the famous arena. After lengthy explanation, they get in to find a defiant former champion.

Joshua describes the night as "a blip", while some of his team sit close by, their heads in their hands. Some lie flat on their backs and stare at the ceiling.

"It was a difficult night. As difficult as it can get," said his trainer Robert McCracken.

Reporters set up cameras outside Madison Square Garden and shoot live into breakfast shows back in the UK. Bunce stays up all night to talk boxing to countless outlets.

Hearn goes back to his hotel and cannot sleep all night, while Joshua and his team return to the Manhattan house they have rented.

He stays in there for the next three days.

"You're either in the house or it's mental outside," recalls manager Cunningham. "You're kind of stuck. You had the house to kind of process it all.

"But the people who have always been there were there. It was deflating but there was a feeling like nothing changes, so how do we help?"

Highlights play out on US breakfast shows. The chubby man beat the Adonis. This was a tale to inspire those who have never even watched boxing. Joshua, on his US debut, had been laid bare - and it was brutal.

"I remember seeing him maybe two weeks after and you could tell he wasn't in a good place," adds Hearn.

"It took him a long while to get in a good frame of mind but we made our decision on a rematch quickly."

As Ruiz, Mexico's first heavyweight world champion, met the country's president and appeared on late-night US talk shows, those on the opposite side were beginning to feel the pain.

"I didn't realise how hard it hit me mentally, emotionally and even physically," says Hearn.

"The week after I had a Gennady Golovkin fight week, then I had my 40th birthday in Ibiza with friends and was still gutted. A week after that I felt utterly drained, run down and mentally low."

Ruiz, as he did throughout the biggest fight week of his life, was still smiling as he paraded on the back of a convertible Rolls Royce through his city of residence in California.

Weeks earlier he had stood on that New York roof-top in baggy jeans, trainers and an ill-fitting blazer, with his hands in his pockets and the air of a man who was simply grateful to be asked questions.

He was not treated like a champion. He did not look like a champion. And yet, six days on - despite a widespread lack of belief - he was one.

He had the night of his life. It was one the sporting world will never forget.

Joshua, now 30, was making his US debut at a venue often dubbed the 'Mecca of boxing'

Backstage, Callum Smith is being drug-tested after retaining his world title in three rounds. "All the testers were watching the Joshua fight on the TV and joking, saying: 'I think this one will be over quicker than your fight,'" he tells BBC Sport.

The testers may be on to something because Ruiz is swiftly floored, only to rise and drop Joshua twice by the end of round three.

"If you hit him you will slow him right down," Joshua is told by his trainer Rob McCracken.

In the opposite corner, seconds before round seven, Robles tells Ruiz: "You know you got him hurt now, so start going for the head."

British entertainer James Corden is open-mouthed at ringside. He intermittently shouts "come on AJ" in spurts, but for the most part, he is frozen, like most around him.

David Haye cannot sit down, much to the frustration of the reporter sitting behind him. As the drama unfolds, the former world heavyweight champion is the only man rising and falling more frequently than his humbled compatriot in the ring.

A third and fourth knockdown come in the seventh. Every time Joshua hits the canvas photographers lift cameras next to the ring, some within jabbing distance of his head. He is exposed and isolated as millions watch an iconic shock play out.

"I felt numb really," promoter Eddie Hearn tells BBC Sport. "I've seen so much in boxing - injuries, tragedy, ups and downs. You can become numb to the drama, but there was a little bit of disbelief."

Joshua, beaten, is on one knee in the corner of the ring. He has a towel draped over his head. His long-term manager Freddie Cunningham is standing over him with concern etched on his face.

"You can't have a mentality where you prepare for that, so everyone is kind of dealing with it at that current time," says Cunningham.

"Forget about sport. Seeing someone you know well not looking at 100%, there is huge concern. It is a friendship and that kicks in straight away."

In Cunningham's words, "things seem to move faster in an arena than a stadium" - and the fight and its aftermath are frenetic.

Rumours hit ringside, ranging from Joshua being unwell to him collapsing backstage earlier in the night. His team will later deny them. His dad is in the ring berating Hearn.

Joshua exits. His acceptance of defeat will be criticised. He can do nothing right on this night.

Ruiz leaves the ring. Draped in belts, he walks out of the arena and through corridors where he is yelled at: "You shocked the world champ. The whole world loves you baby." He can do nothing wrong on this night.

The hopeless, overweight, smiling underdog - nicknamed "destroyer" because he broke things as a child - was a wrecking ball.

There is media panic. On a boxing night for the ages, every word of reaction has become precious.

Joshua, now 30, was making his US debut at a venue often dubbed the 'Mecca of boxing'

Backstage, Callum Smith is being drug-tested after retaining his world title in three rounds. "All the testers were watching the Joshua fight on the TV and joking, saying: 'I think this one will be over quicker than your fight,'" he tells BBC Sport.

The testers may be on to something because Ruiz is swiftly floored, only to rise and drop Joshua twice by the end of round three.

"If you hit him you will slow him right down," Joshua is told by his trainer Rob McCracken.

In the opposite corner, seconds before round seven, Robles tells Ruiz: "You know you got him hurt now, so start going for the head."

British entertainer James Corden is open-mouthed at ringside. He intermittently shouts "come on AJ" in spurts, but for the most part, he is frozen, like most around him.

David Haye cannot sit down, much to the frustration of the reporter sitting behind him. As the drama unfolds, the former world heavyweight champion is the only man rising and falling more frequently than his humbled compatriot in the ring.

A third and fourth knockdown come in the seventh. Every time Joshua hits the canvas photographers lift cameras next to the ring, some within jabbing distance of his head. He is exposed and isolated as millions watch an iconic shock play out.

"I felt numb really," promoter Eddie Hearn tells BBC Sport. "I've seen so much in boxing - injuries, tragedy, ups and downs. You can become numb to the drama, but there was a little bit of disbelief."

Joshua, beaten, is on one knee in the corner of the ring. He has a towel draped over his head. His long-term manager Freddie Cunningham is standing over him with concern etched on his face.

"You can't have a mentality where you prepare for that, so everyone is kind of dealing with it at that current time," says Cunningham.

"Forget about sport. Seeing someone you know well not looking at 100%, there is huge concern. It is a friendship and that kicks in straight away."

In Cunningham's words, "things seem to move faster in an arena than a stadium" - and the fight and its aftermath are frenetic.

Rumours hit ringside, ranging from Joshua being unwell to him collapsing backstage earlier in the night. His team will later deny them. His dad is in the ring berating Hearn.

Joshua exits. His acceptance of defeat will be criticised. He can do nothing right on this night.

Ruiz leaves the ring. Draped in belts, he walks out of the arena and through corridors where he is yelled at: "You shocked the world champ. The whole world loves you baby." He can do nothing wrong on this night.

The hopeless, overweight, smiling underdog - nicknamed "destroyer" because he broke things as a child - was a wrecking ball.

There is media panic. On a boxing night for the ages, every word of reaction has become precious.

Ruiz, who turned 30 in September, was born in Imperial, California

Britain's Smith is holding his news conference as the world's media flood into the room, fresh from the Joshua drama a few metres away. Cameras are being erected at speed, people are on phones, others are asking where Joshua is and word breaks he is having a concussion test.

"I felt awkward. I remember thinking that there is no-one in here who cares about what I am about to say," recalls Smith. "It felt like someone had died in there at times."

Ruiz enters to applause and cheering from some. One man is shouting: "The champ is here." Hearn, one of the sport's smoothest talkers, speaks on stage but still looks a touch dazed. His friends back in the UK are texting him asking if he is OK.

"You have to stay focused. I had a job to do," he remembers.

Ruiz tells his mother he loves her, prompting her blown kiss.

His trainer, a man who says he arrived in the US as an illegal immigrant as a child, is breaking down. He lost his father, job and home in 2007. Questions about his boxing-enthusiast dad reduce him to tears. Triumph reminds him of the wife that stuck with him through it all.

Joshua is in the dressing room used by the New York Knicks. BBC commentator Mike Costello is outside one door, his Radio 5 Live sidekick Steve Bunce is at the other exit. Joshua is pinned in because his post-fight interview is the one everyone desperately wants to hear.

"It had gone midnight and I was there for well over an hour, maybe close to two," says Costello.

"I could see directly down the corridor leading to the arena, where staff were de-rigging the ringside furniture in readiness for a Billy Joel concert the next evening. 'Life goes on,' I thought, even though it felt to many of us as though the world had stopped turning."

Joshua, flanked by his team, emerges. Bunce is primed.

"I was by the service elevator, the one that can hold golf carts ferrying VIPs and also fallen world champions and their entourages of 30 or so people," says Bunce.

"The place had fallen quiet. At one point the lift arrived, doors opened and Ruiz and his people emerged, laughing and smiling. It soon went silent again for a very long time.

"AJ was first out of the back door of the changing room, paused for a moment and then smiled when he saw me. I asked him the first questions as we all filled the lift."

Back at the news conference, Ruiz departs and media are told Joshua will not be attending. Journalists wait and are told again and again. Eventually, large numbers begin to leave.

"AJ was concussed and the doctor said to him: 'Don't do a news conference,'" says Hearn. "When he got showered and I saw him, he said we should do it. I was telling him to leave it."

Through texts and social media, a handful of the departed reporters hear Joshua will turn up. They race back but security insists no-one re-enters the famous arena. After lengthy explanation, they get in to find a defiant former champion.

Joshua describes the night as "a blip", while some of his team sit close by, their heads in their hands. Some lie flat on their backs and stare at the ceiling.

"It was a difficult night. As difficult as it can get," said his trainer Robert McCracken.

Reporters set up cameras outside Madison Square Garden and shoot live into breakfast shows back in the UK. Bunce stays up all night to talk boxing to countless outlets.

Hearn goes back to his hotel and cannot sleep all night, while Joshua and his team return to the Manhattan house they have rented.

He stays in there for the next three days.

"You're either in the house or it's mental outside," recalls manager Cunningham. "You're kind of stuck. You had the house to kind of process it all.

"But the people who have always been there were there. It was deflating but there was a feeling like nothing changes, so how do we help?"

Highlights play out on US breakfast shows. The chubby man beat the Adonis. This was a tale to inspire those who have never even watched boxing. Joshua, on his US debut, had been laid bare - and it was brutal.

"I remember seeing him maybe two weeks after and you could tell he wasn't in a good place," adds Hearn.

"It took him a long while to get in a good frame of mind but we made our decision on a rematch quickly."

As Ruiz, Mexico's first heavyweight world champion, met the country's president and appeared on late-night US talk shows, those on the opposite side were beginning to feel the pain.

"I didn't realise how hard it hit me mentally, emotionally and even physically," says Hearn.

"The week after I had a Gennady Golovkin fight week, then I had my 40th birthday in Ibiza with friends and was still gutted. A week after that I felt utterly drained, run down and mentally low."

Ruiz, as he did throughout the biggest fight week of his life, was still smiling as he paraded on the back of a convertible Rolls Royce through his city of residence in California.

Weeks earlier he had stood on that New York roof-top in baggy jeans, trainers and an ill-fitting blazer, with his hands in his pockets and the air of a man who was simply grateful to be asked questions.

He was not treated like a champion. He did not look like a champion. And yet, six days on - despite a widespread lack of belief - he was one.

He had the night of his life. It was one the sporting world will never forget.

Ruiz, who turned 30 in September, was born in Imperial, California

Britain's Smith is holding his news conference as the world's media flood into the room, fresh from the Joshua drama a few metres away. Cameras are being erected at speed, people are on phones, others are asking where Joshua is and word breaks he is having a concussion test.

"I felt awkward. I remember thinking that there is no-one in here who cares about what I am about to say," recalls Smith. "It felt like someone had died in there at times."

Ruiz enters to applause and cheering from some. One man is shouting: "The champ is here." Hearn, one of the sport's smoothest talkers, speaks on stage but still looks a touch dazed. His friends back in the UK are texting him asking if he is OK.

"You have to stay focused. I had a job to do," he remembers.

Ruiz tells his mother he loves her, prompting her blown kiss.

His trainer, a man who says he arrived in the US as an illegal immigrant as a child, is breaking down. He lost his father, job and home in 2007. Questions about his boxing-enthusiast dad reduce him to tears. Triumph reminds him of the wife that stuck with him through it all.

Joshua is in the dressing room used by the New York Knicks. BBC commentator Mike Costello is outside one door, his Radio 5 Live sidekick Steve Bunce is at the other exit. Joshua is pinned in because his post-fight interview is the one everyone desperately wants to hear.

"It had gone midnight and I was there for well over an hour, maybe close to two," says Costello.

"I could see directly down the corridor leading to the arena, where staff were de-rigging the ringside furniture in readiness for a Billy Joel concert the next evening. 'Life goes on,' I thought, even though it felt to many of us as though the world had stopped turning."

Joshua, flanked by his team, emerges. Bunce is primed.

"I was by the service elevator, the one that can hold golf carts ferrying VIPs and also fallen world champions and their entourages of 30 or so people," says Bunce.

"The place had fallen quiet. At one point the lift arrived, doors opened and Ruiz and his people emerged, laughing and smiling. It soon went silent again for a very long time.

"AJ was first out of the back door of the changing room, paused for a moment and then smiled when he saw me. I asked him the first questions as we all filled the lift."

Back at the news conference, Ruiz departs and media are told Joshua will not be attending. Journalists wait and are told again and again. Eventually, large numbers begin to leave.

"AJ was concussed and the doctor said to him: 'Don't do a news conference,'" says Hearn. "When he got showered and I saw him, he said we should do it. I was telling him to leave it."

Through texts and social media, a handful of the departed reporters hear Joshua will turn up. They race back but security insists no-one re-enters the famous arena. After lengthy explanation, they get in to find a defiant former champion.

Joshua describes the night as "a blip", while some of his team sit close by, their heads in their hands. Some lie flat on their backs and stare at the ceiling.

"It was a difficult night. As difficult as it can get," said his trainer Robert McCracken.

Reporters set up cameras outside Madison Square Garden and shoot live into breakfast shows back in the UK. Bunce stays up all night to talk boxing to countless outlets.

Hearn goes back to his hotel and cannot sleep all night, while Joshua and his team return to the Manhattan house they have rented.

He stays in there for the next three days.

"You're either in the house or it's mental outside," recalls manager Cunningham. "You're kind of stuck. You had the house to kind of process it all.

"But the people who have always been there were there. It was deflating but there was a feeling like nothing changes, so how do we help?"

Highlights play out on US breakfast shows. The chubby man beat the Adonis. This was a tale to inspire those who have never even watched boxing. Joshua, on his US debut, had been laid bare - and it was brutal.

"I remember seeing him maybe two weeks after and you could tell he wasn't in a good place," adds Hearn.

"It took him a long while to get in a good frame of mind but we made our decision on a rematch quickly."

As Ruiz, Mexico's first heavyweight world champion, met the country's president and appeared on late-night US talk shows, those on the opposite side were beginning to feel the pain.

"I didn't realise how hard it hit me mentally, emotionally and even physically," says Hearn.

"The week after I had a Gennady Golovkin fight week, then I had my 40th birthday in Ibiza with friends and was still gutted. A week after that I felt utterly drained, run down and mentally low."

Ruiz, as he did throughout the biggest fight week of his life, was still smiling as he paraded on the back of a convertible Rolls Royce through his city of residence in California.

Weeks earlier he had stood on that New York roof-top in baggy jeans, trainers and an ill-fitting blazer, with his hands in his pockets and the air of a man who was simply grateful to be asked questions.

He was not treated like a champion. He did not look like a champion. And yet, six days on - despite a widespread lack of belief - he was one.

He had the night of his life. It was one the sporting world will never forget.DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

Latest Stories

-

Government initiates comprehensive review of VAT regime – Dr Ato Forson

7 minutes -

Dr Cassiel Ato Forson elected Chairman of ECOWAS Bank for Investment and Development

15 minutes -

Gov’t must remain neutral in managing Bawku conflict – Former MP

17 minutes -

Let’s take over our sanitation management – MMDAs appeal to government

35 minutes -

Samant D’Legend bounces back with ‘Last Straw’ EP

47 minutes -

Gospel musician Joseph Matthew marries in colourful wedding ceremony

1 hour -

Equity Health Insurance initiates NHIS Top-Up at Madina Market

1 hour -

Killing of nurse in Yamfo: IGP dispatches PIPS team as part of investigations

1 hour -

Ubuntu Records star Brittany Bola unveils visuals for ‘Reasons’

1 hour -

BRUHM engages communities and expands retail presence in Ghana

2 hours -

Never stop believing in yourself – Jah Manny urges up and coming artistes

2 hours -

Military needs to take control of some parts of Binduri – MP

2 hours -

QNET addresses misconceptions and misrepresentations about its business model in Ghana

2 hours -

IGP receives CDS at National Police Headquarters with a guard of honour

2 hours -

KNUST career services centre and SEO Africa host information session for students

2 hours