Audio By Carbonatix

When I ask the creator of the hit Korean drama Squid Game about reports that he was so stressed while shooting the first series he lost six teeth, he quickly corrects me. “It was eight or nine,” he laughs.

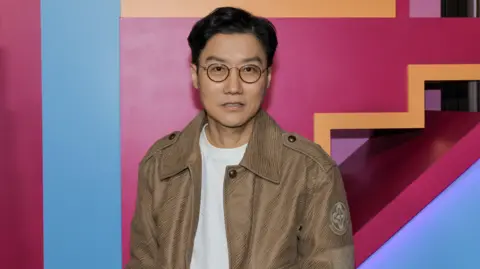

Hwang Dong-hyuk is speaking to me on set as he films the second series of his dystopian Netflix thriller, which sees hundreds of debt-laden contestants fight it out for a whopping cash prize, by playing a string of life-or-death children’s games.

But another series was not always on the cards. At one point, he swore against making one.

Given the stress it has caused him, I ask what changed his mind.

“Money,” he answers, without hesitation.

“Even though the first series was such a huge global success, honestly I didn’t make much,” he tells me. “So doing the second series will help compensate me for the success of the first one too.”

“And I didn’t fully finish the story,” he adds.

The first series was Netflix’s most successful show to date, thrusting South Korea and its home-grown television dramas into the spotlight. Its dark commentary on wealth inequality touched a nerve with audiences around the globe.

But having killed off almost every character, Hwang has had to start from scratch, with a new cast and set of games, and this time audience expectations are sky high.

“The stress I feel now is much greater,” he says.

Three years after the first series aired, Hwang is even more pessimistic about the state of the world.

He points to current wars, climate change and a widening global wealth gap. Conflicts are no longer confined between the rich and poor, they are playing out intensely between different generations, genders and political camps, he says.

“New lines are being drawn. We’re in an era of us vs them. Who’s right and who’s wrong?”

As I toured the show’s playful set, with its distinctive brightly-coloured staircase, I picked up a few clues as to how the director’s despair will be reflected this time around.

In this series, the previous winner, Gi-hun, re-enters the game on a quest to bring it down and save the latest round of contestants.

According to Lee Jung-jae, who plays the leading character, he is "more desperate and determined” than before.

The floor of the dormitory, where the contestants sleep at night, has been divided in two.

One half is branded with a giant red neon X symbol, the other with a blue circle.

Now, after every game, the players must pick a side, depending on whether they want to end the contest early and survive, or keep playing, in the knowledge all but one of them will die. The majority decision rules.

This, I am told, will lead to more factionalism and fights.

It is part of director Hwang’s plan to expose the dangers of living in an increasingly tribal world. Forcing people to pick sides, he believes, is fuelling conflict.

For all those who were captivated by the shocking storytelling of Squid Game, others found it gratuitously violent and difficult to watch.

But it is clear from talking to Hwang, that the violence is fully thought out. He is a man who thinks and cares deeply about the world and is motivated by a mounting unease.

“When making this series, I constantly asked myself ‘do we humans have what it takes to steer the world off this downhill path?’. Honestly, I don’t know,” he says.

While viewers of the second series might not get the answers to these big life questions, they can at least be comforted that some plot holes will be filled in – like why the game exists, and what is motivating the masked Front Man running it.

“People will see more of the Front Man’s past, his story and his emotions,” reveals the actor Lee Byung-hun, who plays the mysterious role.

“I don't think this will make viewers warm to him, but it may help them better understand his choices.”

As one of South Korea’s most famous actors, Lee admits that having his face and eyes covered and his voice distorted throughout the first series, was “a little bit dissatisfying”.

This series he has relished having scenes without a mask, in which he can fully express himself – a chance he nearly did not get.

Hwang tried for 10 years to get Squid Game made, taking out large loans to support his family, before Netflix swooped in.

They paid him a modest upfront amount, leaving him unable to cash in on the whopping £650m it is estimated to have made the platform.

This explains the love-hate relationship South Korea’s film and television creators currently have with international streaming platforms.

Over the past few years, Netflix has stormed the Korean market with billions of dollars of investment, bringing the industry global recognition and love, but leaving creators feeling short-changed.

They accuse the platform of forcing them to relinquish their copyright when they sign contracts – and with it, their claim to profit.

This is a worldwide problem.

In the past, creators could rely on getting a cut of box office sales or TV re-runs, but this model has not been adopted by streaming giants.

The issue is compounded in South Korea, creators say, due to its outdated copyright law, which does not protect them.

This summer, actors, writers, directors and producers teamed up to form a collective, to fight the system together.

“In Korea, being a movie director is just a job title, it’s not a way to earn a living,” the vice-president of the Korean Film Directors Guild, Oh Ki-hwan, tells the audience at an event in Seoul.

Some of his director friends, he says, work part-time in warehouses and as taxi drivers.

Park Hae-young is a writer at the event. When Netflix bought her show, 'My Liberation Notes', it became a global hit.

“I’ve been writing my whole life. So, to get global recognition when competing with creators from across the world, has been a joyful experience,” she tells me.

But Park says the current streaming model has left her reluctant to “pour her all” into her next series.

“Usually, I’ll spend four or five years making a drama in the belief that, if it's successful, it could somewhat secure my future, that I'll get my fair share of compensation. Without that, what's the point of working so hard?”

She and other creators are pushing the South Korean government to change its copyright law to force production companies to share their profits.

In a statement, the South Korean government told the BBC that while it recognised the compensation system needed to change, it was up to the industry to resolve the issue. A spokesperson for Netflix told us it offers “competitive” compensation, and guarantees creators “solid compensation, regardless of the success or failure of their shows”.

Squid Game’s Hwang hopes his candor over his own pay struggles will initiate that change.

He has certainly sparked the fair pay conversation, and this second series will surely give the industry another bump.

But when we catch up after filming has wrapped, he tells me his teeth are aching again.

“I haven’t seen my dentist yet, but I’ll probably have to pull out a few more very soon.”

The second series of Squid Game will be released on Netflix on 26 December 2024.

Latest Stories

-

GHS warns of rise in road traffic accidents during Christmas festivities

9 minutes -

PMI Ghana advocates for project management act after touring critical Accra-Tema Motorway & Extension Project

9 minutes -

Gender Ministry demands justice for abused 6-year-old in Asamankese

21 minutes -

Let’s build a bridge between ECOWAS and Sahel States – Mahama

27 minutes -

Hindsight: Is the GPL competitive, or are teams just inconsistent?

27 minutes -

Ghana’s diplomatic counterstrike: Vindication of sovereign dignity

27 minutes -

We’re committed to two-term presidential limit — NDC

28 minutes -

Zenith Bank Ghana kicks off the Christmas season with 2025 carols night celebration

28 minutes -

African films must be told with purpose and excellence to compete globally – Veep

37 minutes -

Access Bank Ghana wins 2 honours at 2025 Sustainability & Social Investment Awards

42 minutes -

Kuami Eugene takes rebranded highlife concert to Kumasi

43 minutes -

Africa Education Watch urges Parliament to act as truancy rises in Northern Ghana

47 minutes -

Rotary Club of Accra-Odadee AOGA suupports Awaawaa2 Centre with essential items

50 minutes -

Ghana hasn’t mustered courage to enforce compulsory basic education – Kofi Asare

54 minutes -

Hubtel named Overall Best Fintech Partner at 2025 Fintech Stakeholder Dinner & Awards

58 minutes