Private transport is one of the world’s biggest sources of greenhouse gases, with emissions rising every year.

In our car dominated cities, can we cut down the carbon footprint of our daily commute?

For many people, the journey to and from work are the bookends of the daily grind. But how we choose to travel to the office, or even to pop to the shops, is also one of the biggest day-to-day climate decisions we face.

In countries like the UK and the US, the transport sector is now responsible for emitting more greenhouse gases than any other, including electricity production and agriculture. Globally, transport accounts for around a quarter of CO2 emissions.

And much of the world’s transport networks still remain focused around the car. Road vehicles – cars, trucks, buses and motorbikes – account for nearly three quarters of the greenhouse gas emissions that come from transport.

So, the way you get around each day can make a big difference to your own carbon footprint.

If you use a car frequently, the first step to cutting down your emissions may well be to simply fully consider the alternatives available to you.

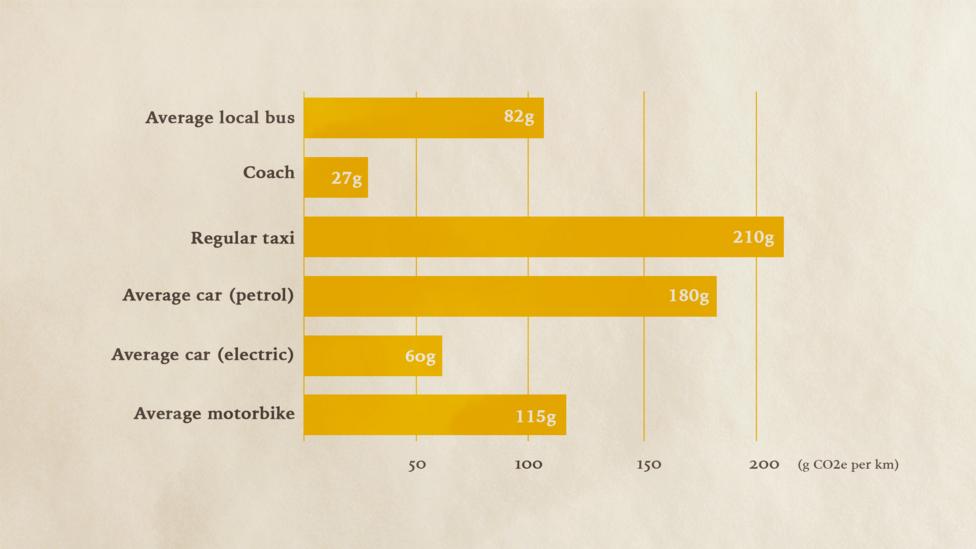

The average petrol car on the road in the UK produces the equivalent of 180g of CO2 every kilometre, while a diesel car produces 173g of CO2/km. In the US the average passenger vehicle on the road releases 650g of CO2/km. Generally, the larger the car, the higher the emissions.

Driving a newer vehicle can reduce these emissions – in Europe the average emissions for a new petrol car in 2018 was 123g of CO2/km.

But in many cases it may be possible to avoid using the car altogether. In many countries, even short journeys which could often be made on foot or by bike are usually made by car. In England, for instance, around 60% of 1-2 mile trips are made by car.

“From our perspective, the really low hanging fruit is the journeys that people could walk,” says Stephen Edwards, head of policy and communications at Living Streets, a British charity that promotes walking. “There's an immediate contribution that we could all make to reducing our personal carbon emissions by walking more of those short journeys, whether it be to school, to the shops, to work or to the station.”

People often face psychological barriers to walking, says Edwards, and Living Streets aims to support people as they try to change their behaviour. During National Walking Month in May, it encourages people to substitute just one short car journey a day for a walk, and to experiment with incorporating walking into their daily routine.

Electric bikes and networks of segregated cycle lanes are beginning to change what is possible in terms of commuting distance

“I think once people start making that change, then it becomes sustained over time and the majority keep it up after May,” says Edwards.

Reducing car use on the school run is another focus for Living Streets. A generation ago, 70% of British children walked to school, but now less than half do, despite studies showing children who walk or bike to school tend to be more focused and are less likely to be overweight. Fewer cars around the school gate also means less local air pollution.

Dom Jacques, a parent of two from Leeds, in the UK, decided to do something when he became frustrated at the amount of congestion at the gates of his children’s school. Concerned about the potential impacts of air pollution and chaotic traffic on small children, he set up a local group to advocate for fellow parents to avoid driving their cars up to the school, and convinced the school to become involved with the Living Streets walk to school programme.

“The children were being educated about the benefits of walking on a daily basis,” he says. “They log their journeys on a daily basis as part of the project, they get really involved in the process… Then you can track whether or not you’ve been successful. It gives you a real insight into what’s happening.”

Living Streets says walk to school rates have increased by 23% after five weeks in schools where its programme have been implemented, while car journeys have fallen by around 30%.

Cycling, which shares many of the climate benefits of walking, is increasingly a viable alternative to car journeys, too. Some countries have sped ahead in bike transport: in the Netherlands 26% of journeys are made by bike, followed by Denmark on 18% and 10% in Germany. All three countries had major policy changes in the 1970s and 1980s that led to a large increase in cycling, and all still continue to invest in cycling infrastructure.

Often people may discard cycling as a viable option for longer distance travel. But electric bikes and networks of segregated cycle lanes are beginning to change what is possible in terms of commuting distance, says Leo Murray, director of innovation at climate change charity Possible (formerly 10:10 Climate Action).

In Copenhagen’s Farum cycle superhighway, the average bike commute is now 15km (9 miles), largely thanks to electric bikes. A recent report from advocacy organisation Transport for Quality of Life argued evidence from Europe shows electric bikes can transform our cities and should be financially incentivised in places like the UK.

“Journeys that you just wouldn't have made by bike before, now are actually trivial to make by e-bike,” says Murray. “And they are faster because you never sit in a traffic jam. The same is true to an extent for electric scooters.”

Many people, though, view public transport as the most obvious way to reduce their transport emissions, and it is especially important in the most congested urban areas. “All the economics are points in favour of it,” says Claire Haigh, chief executive of British sustainable travel organisation Greener Journeys.

Travelling on light rail or the London Underground emits around a sixth of the equivalent car journey, according to UK government figures. A coach ride produces lower emissions still.

Taking the local bus currently emits more, perhaps because the vehicles travel at lower speeds and pull over more often. But taking a local bus emits a little over half the greenhouse gases of a single occupancy car journey and also help to remove congestion from the roads. Bus emissions will go down further as more and more cities implement plans for electric and hydrogen buses.

Walking to and from the bus stop also gives people on average half their weekly recommended exercise, according to Greener Journeys research. “The great thing about public transport is it is also active,” says Haigh.

It is important to recognise, however, that tackling emissions from transport also relies on structural changes which people may not be able to influence by their daily habits. “The motor car dominance means that it actively militates against you making more responsible choices,” says Murray. “What you have to do is change the conditions in which the choices are being made so they are more favourable to more responsible choices.”

Local authorities and policy makers around the world need to implement measures to help these journeys become both more feasible and attractive. People will be more likely to want to walk and cycle if measures to make streets feel safer and more pleasant – such as low speed zones for cars, widening pavements or building bike lanes – are put in place. Likewise, buses will be much more attractive if the routes are convenient and well communicated, bus lanes are available, and buses are accessible and welcoming. In some cases, it can even make sense to make them free.

But this does not mean people should simply wait for a public authority to cut the carbon footprint of their daily travel for them – quite the opposite, says Murray. “You can campaign in your local community, work through residents’ associations, work with your neighbours, to help to change the choice architecture that is determining everybody's decisions.”

As Haigh puts it, “If you don't ask, you don't get”.

For example, Murray, who lives on a garden square in West London, teamed up with other residents in the neighbourhood to push his local council to install on-street electric vehicle chargers, for which there was a government grant available. After realising there was demand from several families, the council installed the chargers.

“We now have electric charge points installed in the lamp post on my square,” he says. “As a consequence, three households on the square have now switched to electric vehicles.”

Murray and a group of local parents similarly advocated for a proposed cycle lane near his house. “We formed effectively a council lobby that has helped to embolden the council to proceed with these plans,” he says.

There are many innovative ideas being implemented in cities around the world to help people reduce the carbon footprint of their daily commute, says Edwards. The Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo, for example, has embraced the idea of a 15-minute city, where all the services people need – including their workplaces – are situated in close proximity to where they live. It would require a drastic redesign of Paris city centre, but the benefits would be huge.

“That is about planning urban development so that wherever people live, everything that they need is within 15 minutes of walking or cycling or public transport,” says Murray. “Arranging urban spatial geography around that basic organising principle is actually the most important thing that you can do to start to erode car dominance.”

Of course, there are some journeys that will always be tricky to do by public transport, bike or foot. For many living in rural areas, for instance, the car is often the only realistic transport option. Similarly, for elderly people or those with a disability, cars may be the only feasible means of transpor

For those continuing to use a car, choosing the most fuel-efficient model available can make a big difference. Transport emissions are still growing globally because of the growing appetite for SUVs over smaller vehicles, a trend which risks cancelling out the benefits switching to electric cars. A decade ago SUVs made up 17% of global yearly car sales, but now account for 39%. According to the International Energy Agency, this demand for larger cars was the second largest contributor to the increase in global CO2 emissions between 2010 and 2018.

“Not only are people driving more, but also the vehicles, unfortunately, aren't actually getting more carbon efficient,” says Heigh. “So that's a big problem.”

A large car emits on average 85% more greenhouse gases per km than a small vehicle, according to figures from the UK government. Electric cars are the lowest carbon – they emit around a third of the CO2 of a petrol car in the UK, although this figure will vary from country to country depending on how much fossil fuels are still used to produce electricity. The car stock on the roads will also alter this – cars on the roads in the US are generally larger and less efficient than those in Europe, for example.

Car sharing initiatives, which allow you to rent a car without owning one, are increasingly becoming an option for those living in cities and towns. Studies have shown these have the ability to significantly reduce the number of cars on the roads.

“In a context where you've actually got public authority bringing in policies to make private car ownership and use less attractive, these are probably a very important part of the solution,” says Murray.

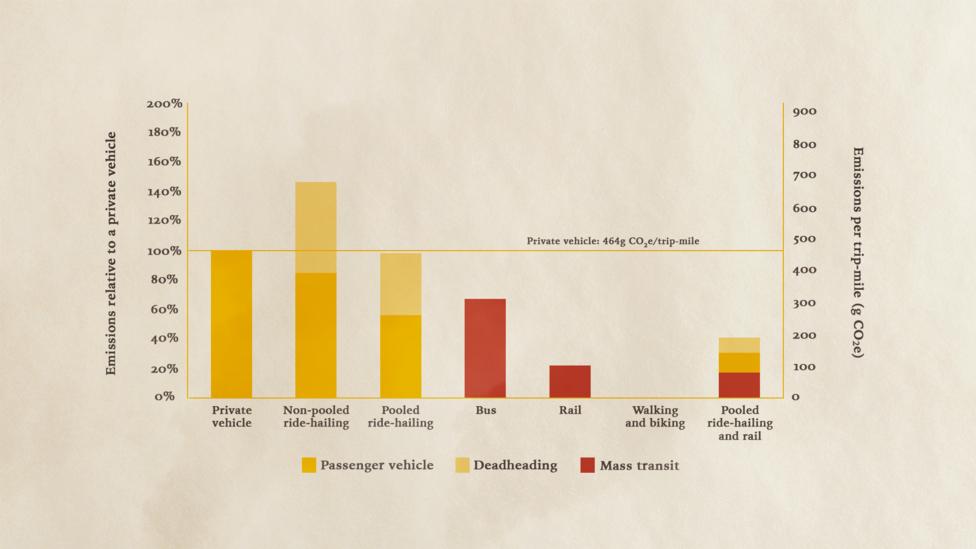

For some, a sensible-seeming solution would be to turn to taxis and ride hailing through apps such as Uber and Lyft. But these may be higher carbon emitters than you realise. One recent report by the Union of Concerned Scientists in the US found ride-hailing services emits 69% more climate pollution on average than the journeys they displace, and 47% more than an equivalent private car ride due to the extra passenger-free driving they do while waiting for a fare – known as "deadheading". But pooling rides, choosing rides in electric vehicles, or using ride hailing to connect with public transport all produce less emissions than a private car, the report found. And ride hailing will also reduce the need for on-street parking – freeing up more space in dense cities.

Some countries are now seeing innovative new alternatives appearing, such as on-demand buses and other “microtransit” options. Arrivaclick’s flexible minibus service, for example, has begun schemes in Liverpool, Leicester and Watford, while startup Via has launched a pilot on-demand shuttle in Cupertino, California. Until schemes like this become more mainstream, however, car-pooling remains one of the main options for reducing your individual emissions of using a car.

“One thing that would be really good would be if people could just think, don't ever go in a car on your own,” says Haigh. “If you're going to do a journey by car, make sure you fill that car up with at least one other person.”

One last way you may be inadvertently leading to transport emissions and congestion in your area is your online shopping habits. The huge growth in internet shopping has caused the number of vans to skyrocket in many cities due to home deliveries.

But the change in greenhouse gas emission impacts from home deliveries is still uncertain, says Susan Shaheen, co-director of the Transportation Sustainability Research Center at the University of California. “While e-commerce can create demand for additional deliveries, it can also reduce the number of retail trips a household makes,” she says.

In either case, one way to reduce home delivery emissions is for packages to arrive using postal services, which typically serve a location once a day, says Shaheen. You could also get parcels delivered to your local post office, avoid one-day deliveries and use companies that deliver using low carbon transport.

For many of us, taking action to reduce the emissions from your daily transport can be tricky on an individual level, but even just cutting out one or two journeys could make a different while pushing those in charge to make it easier for us to switch to greener vehicles.

By doing our bit we may one day be living in the healthy, green cities so many of us dream of.

Latest Stories

-

Mpatasia galamsey pit responsible for 4 deaths in 4 months, undergoes reclamation efforts

49 minutes -

‘Managers of SOEs must skillfully resist political interference’ – Jabesh Amissah-Arthur

1 hour -

Benjamin Asare signs contract extension with Hearts of Oak until 2027

1 hour -

Chaos in Asante Mampong as angry NDC supporters vandalise property, set items ablaze

2 hours -

The ECG Dilemma: We don’t have a fully efficient power value chain – Sulemana Ibrahim

2 hours -

ECG was never at the table in terms of revenue – Dubik Mahama

3 hours -

Kumasi Mayor to commence decongestion of the city on April 16

3 hours -

Per our tradition, we cannot mingle until there’s peace – Spokesperson for Bawku Naba

3 hours -

There was zero investment in ECG during Akufo-Addo’s first tenure – Dubik Mahama

4 hours -

Queen Titiaka partners Forestry Commission and others to bring climate-inspired hope to inmates of Nsawam Female Prisons

4 hours -

2030 World Cup: CONMEBOL proposes expanded 64-team tournament

4 hours -

EU to invest €300m to boost water provision in Greater Tamale

4 hours -

Playback: JoyNews held National Dialogue on ECG’s future

5 hours -

Teacher trainee allowance arrears fully paid – Students Loan Trust Fund

5 hours -

Cargill, ICI celebrate graduation of 60 youth from cocoa-growing communities

5 hours