Audio By Carbonatix

Reporting cases of gender-based violence may aid survivors in receiving medical, psychological, and legal assistance. It can also help with resource allocation for these services, but survivors are hesitant to report GBV incidents. Zubaida Mabuno Ismail finds out why?

If you ask Ghanaians about gender-based violence, three in four might tell you that it is not very common, while nearly nine in 10 will tell you that physical violence is never justified. This is according to findings from an Afrobarometer survey of 2,400 Ghanaians published in October 2022.

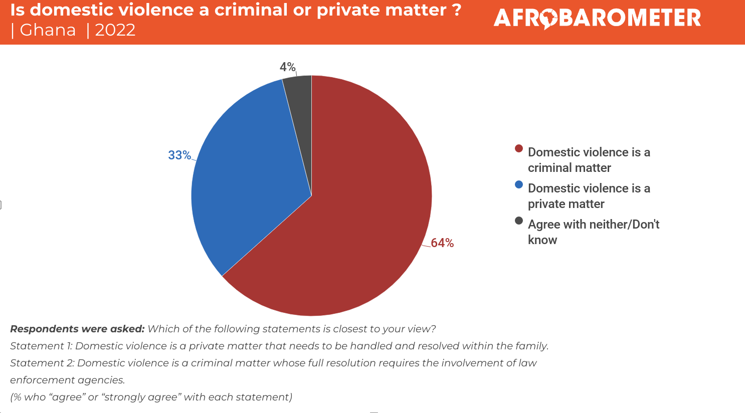

Further, nearly two in three said that domestic violence is a criminal matter that should never be resolved privately in the family, and nine in 10 had faith that the police would take cases of domestic violence seriously.

Despite these perceptions, women hesitate to report cases of gender-based violence to the police for various reasons.

For Adwoa (not her real name), the fear of losing her marriage keeps her from telling anyone about the violence from her husband. She points to a scar on her cheek, the evidence of the most recent violence meted out by her husband because she didn’t tell him about a change in dinner plans. Her husband wanted soup and fufu (a local staple made from cassava), but Adwoa was too tired to pound fufu, so she made rice to go with the soup.

She neither reported the abuse to her younger brothers, who would have issued a stern warning to her partner nor to the police because she feared it would end her marriage.

“I am afraid I will lose my man if I go to the police, so I choose to deal with it privately," she explains.

The fear of divorce is one of the reasons cited in a qualitative study on motivations and barriers to help-seeking behaviour by women who had suffered intimate partner violence in Ghana. The study also found that stigma, cultural norms on gender roles and expectations, family privacy, and a lack of trust in formal support channels kept women from telling anyone about the violence they faced at home.

According to the mental health information and news website Psych Central, another reason why women don’t report is denial and minimisation, whereby women don’t believe that what they have suffered is abuse or downplay the harm of the abuse.

This was the case for Marian Ayisi, a public servant and business owner who resides in Accra’s Spintex neighbourhood. She endured anxiety-inducing silent treatment from her husband for a week, but what is well-defined as emotional abuse in Ghana’s Domestic Violence Act did not register as such, and therefore, she did not report it to the authorities.

She had asked her husband why he was late in picking their child up from school, and he responded by not speaking to her for a week.

The United Nations defines domestic violence as a pattern of behaviour in any relationship used to gain or maintain power and control over an intimate partner.

Abuse can take many forms, including violence and threats of violence, and includes any action that causes fear, intimidation, terror, manipulation, pain, humiliation, blame, injury, or wound.

However, even though abuse in all forms – physical, sexual, emotional and economic – is well-defined, previous studies have shown that women don’t report gender-based violence due to the belief that violence is normal or that it is not serious enough to report.

Ghanaian respondents to the Afrobarometer survey thought that gender-based violence is uncommon. Still, in 2018, the UN classified domestic violence as a global public health problem, with one in three women experiencing some form of domestic violence.

“Violence by a husband or an intimate male partner (physical, sexual, or psychological) is the most widespread form of violence against women globally,” noted the global agency.

Further, UN Women noted that a woman dies every 11 minutes at the hands of an intimate partner or family member and that one in four women has suffered intimate partner violence.

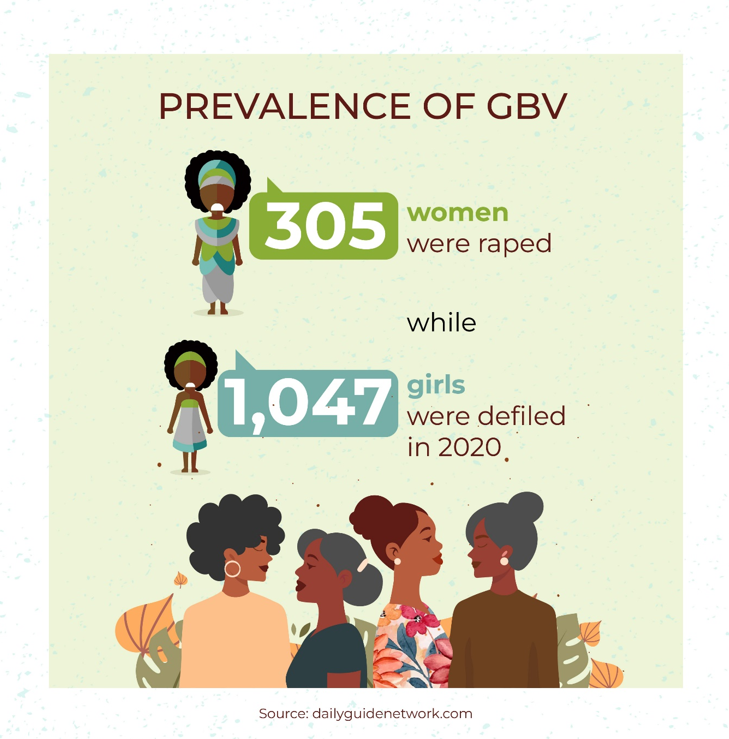

In Ghana, statistics from the Domestic Violence and Victim Support Unit (DOVVSU) of the Ghana Police Service indicated that 131 sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) cases were recorded in Ghana between October 2020 and March 2021.

In 2022, the immediate past Director-General of the Criminal Investigations Department, Commission of Police, Isaac Ken Yeboah revealed that 305 women were raped and 1,047 girls were defiled in 2020 and added that 15,000 cases of violence against women were reported to law enforcement agencies annually.

However, the Domestic Violence Report commissioned by the Ministry of Gender and published in 2016 acknowledged that domestic violence often goes unrecognised and is underreported, mostly due to social norms and cultural beliefs.

Research has shown additional reasons why women don’t report: shame, financial barriers, perceived impunity of perpetrators, lack of awareness of available support services or access to such services, the threat of losing children, fear of getting the offender in trouble, fear of retaliation, attitudes towards victims by law enforcement officials, and distrust of healthcare workers.

UN Women observed that less than four in 10 survivors seek help of any kind, and for those who do, fewer than 10 per cent report to the police.

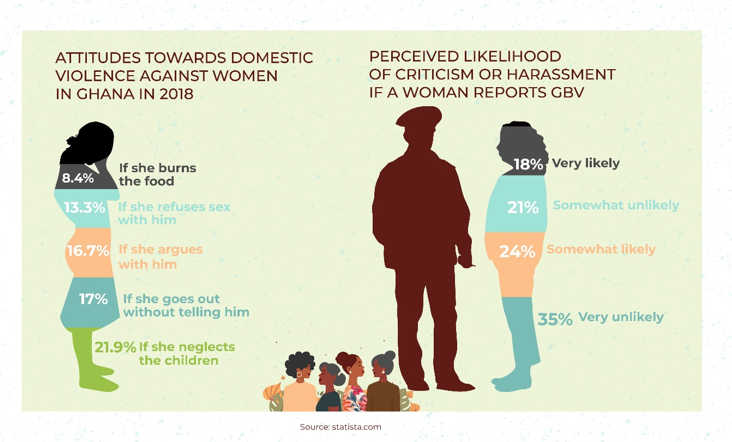

The belief that violence is normal was captured in a 2018 Statista survey on attitudes towards domestic violence, in which most respondents said that a husband is justified in beating his wife for various reasons, including going out without telling him, neglecting the children, arguing with him, refusing sex with him, or burning food.

The research, which drew responses from 19,679 respondents aged between 15 and 49, found that most male and female respondents believed that a husband was justified in beating his wife for any of the reasons that were listed.

These were similar to views captured in the 2016 national survey on domestic violence.

In contrast, the more recent Afrobarometer survey suggested a change in attitudes, with most respondents saying that domestic violence is a criminal matter that should be handled by the police.

However, while many respondents said that police are likely to take cases of GBV seriously, they also said that women are likely to be criticised or harassed for reporting gender-based violence.

Evidence encourages survivors to report cases of gender-based violence so that they can get the support they need after suffering the effects such as injuries and illness.

According to UN Women, rates of depression, anxiety disorders, unplanned pregnancies and sexually-transmitted infections are higher in women who have experienced violence. Moreover, the national domestic violence survey stated that the lives of survivors, especially those who suffered physical violence, were disrupted, keeping them from work and school and interfering with their ability to do domestic work and concentrate on other day-to-day activities. Survivors also had low levels of confidence and lived in fear, and UN Women stated that the effects of violence can last long after the violence has stopped.

Reporting cases of GBV allows survivors to get the support that would mitigate the impact of GBV on their health and lives. A study conducted in Uganda observed that reporting cases of GBV allows survivors to access the medical, psychosocial and legal services they need to minimise the impact of GBV and ensures that perpetrators are held accountable.

“Moreover, formal reporting of SGBV to medical personnel, legal officers, or community leaders allows accurate estimation of the prevalence of the violence, which enables proper resource allocation towards interventions to reduce SGBV and to provide appropriate care to survivors,” observed the researchers.

However, in Ghana and around the world, many survivors do not report to informal (family and friends) or formal (the police or health facilities) channels, with experiences of survivors in Ghana pointing to an unsupportive environment.

Research from the University of Ghana on the perceptions of survivors of domestic violence found that while the 21 survivors interviewed knew at least one government agency responsible for protecting them (mainly DOVVSU), they were dissatisfied with the services. They said the government had failed them through “delays in arresting and prosecuting perpetrators, lack of shelter for victims, and the cost of medical reports in building evidence for their cases.”

According to Akosua Darkwah, Associate Professor of Sociology and Gender Studies at the University of Ghana, the lack of resources and support for survivors fuels the culture of silence, as without them, survivors feel pressure to conform to societal expectations that place value on marriage over their wellbeing.

“Instead of backing survivors’ efforts to speak out, some of their own family members tell them their marriages are superior.

“The onus is on us to create an environment where victims of gender-based violence feel safe enough to speak up without fear of retaliation,” she said.

She added that economic dependence also contributes to a culture of silence.

"When women can't afford to pay the bills for their kids, it makes it hard for them to report their husbands when they abuse them,” she said, adding that even those advising women to stand up against abusive husbands would not offer financial support such as school fees.

“So you have to make sure that you are fully able to take care of the children, and that’s not something that most women can do.”

Dr Darkwah added that the culture of silence is also perpetuated by religious and cultural beliefs and messages from the media which encourage communities to take abuse as a norm rather than an anomaly.

“It is very difficult to stand against these things given what you hear in our churches and mosques, and see in films and books, and on television and radio, unless you have been trained to see the world differently.”

“To be able to say, ‘No, I am not putting up with this’ you need to be more than just emotionally strong-willed; you also need to have been raised in a certain way."

"People will be silent until we have an environment where people are not blamed for reporting these issues, and an environment where we respect survivors," said the sociologist.

This article was produced with the support of the Africa Women’s Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with the International Centre for Journalists (ICFJ) and with support from the Ford Foundation.

The writer is specialised in climate change, biodiversity and gender reporting.

Contact her on zubaidais16@gmail.com

Latest Stories

-

Chamber of Mines proposes sliding royalty of 4%-8%, removal of GSL amid high gold prices

2 hours -

Tesla cuts car models in shift to robots and AI

3 hours -

Prison officer jailed for having sex with inmate in UK

3 hours -

Anthony Joshua fights back tears as he opens up on tragic Nigeria crash

3 hours -

France moves to abolish concept of marital duty to have sex

3 hours -

‘Nkoko Nkitinkiti Project’ processes 50,000 birds at Aglow Farms as Ghana targets 80 million goal

3 hours -

I quashed my beef with AKA before his death – Burna Boy

3 hours -

Nicki Minaj calls herself Trump’s ‘number one fan’ and shows off gold card visa

4 hours -

China to relax travel rules for British visitors, UK says

4 hours -

Money, ‘godfathers’ and cultural stereotypes locking out women and youth from Ghana’s elections – GENCED

4 hours -

Melania Trump documentary not showing in South African cinemas

4 hours -

NPA Chief Executive meets staff to chart renewed path for 2026

4 hours -

Majeed Ashimeru joins RAAL La Louvière on season-long loan from Anderlecht

4 hours -

13 clubs punished for match-fixing in China

4 hours -

GNCCI applauds BoG’s Monetary Policy rate cut, urges banks to lower lending costs

4 hours