Ghana has been ranked 5th in Africa but 24th in the World on humane and health driven drug policies, according to the inaugural edition of the Global Drug Policy Index released by the Harm Reduction Consortium.

The country scored 36 out of an overall 100 marks.

Senegal led the Africa ranking by scoring 53 marks, followed by Morocco (51 of 100), South Africa (47 of 100), Mozambique (40 of 100) then Ghana, in that order.

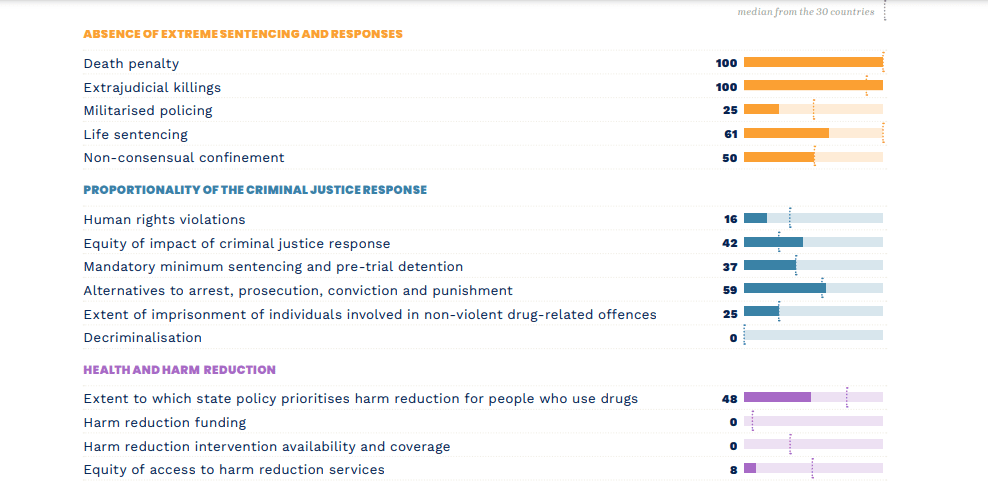

Ghana was ranked 29th with a score of 12 out of 100 for Health and Harm Reduction. It was ranked 18th with a score of 71 out of 100 for Absence of Extreme sentencing and responses for drug use.

Again, the country ranked 22nd with a score of 28 of 100 for Proportionality of the criminal justice response. It came 21st with a score 32 of 100 for Access to, and availability of, internationally controlled medicines for the relief of pain and suffering.

Ghana's performance implies that more needs to be done in the area of health and socio-economic infrastructure in order to strengthen its drug policy to protect especially, its vulnerable people. It shows how much its drug policies and implementation align with the UN principles of human rights, health and development.

It also means that the standards and expectations from civil society experts on drug policy implementation must be strong and improved.

The index is the first-ever accountability tool designed that assesses and ranks countries’ drug policies against key UN-system recommendations.

The Index evaluates the performance of 30 countries covering all regions of the world and is illustrated by real life stories, including people who use drugs, from around the world.

But the researchers say most countries failed drug policy test according to the Index results.

This report provides an overview of key trends, commonalities and differences in drug policies and their implementation in 30 countries, reviewing data from 2020.

How Ghana was scored

The thirty countries were scored under five broad indicators;

- absence of extreme responses

- proportionality of criminal justice response,

- health and harm education,

- development

- the availability of and access to internationally controlled substances for the relief of pain and suffering.

Ghana scored 71 out of 100 in the absence of extreme responses. This includes whether the country retains death penalty for drug offences, the extent of death penalty application for drug offences in the country. It covers extra judicial killing (100 out of 100) and Life sentencing (61 out of 100)– whether there are provisions in legislation or sentencing frameworks for the imposition of life imprisonment for drug offences and how often are they imposed. It also covers militarised policing – to what extent are the military or special security forces involved in drug operations (25 out of 100).

The second indicator was proportionality of criminal justice response. Here Ghana score 28 out of 100.

This indicator covered human right violations (16 out of 100) – that very frequently suspects in drug cases are subjected to violence or torture by the police, that to a large extent there are arbitrary arrest and detention for drug offences. It scored 42 of 100 on equity of impact of criminal justice response – that to what extent does enforcement of drug policy disproportionately impact certain ethnic groups, low-income groups and women.

It scored 37 out of 100 in mandatory minimum sentencing and pre-trial detention – because Ghana’s law does not include mandatory pre-trial detention for drug offences, that it laws include mandatory minimum sentences for any drug offences, and those mandatory minimum sentences apply to the first offences. It scored zero for decriminalization policy – that there are no laws decriminalization of drug use.

Another indicator was harm reduction for which Ghana scored 12 out of 100.

It covers the extent to which state policy prioritizes harm reduction for people who use drugs (48 out of 100) – because people who use drugs are included in the HIV national strategic plan and specified as key and vulnerable targeted population, that people who use drugs are not included in Tuberculosis national strategic plan.

With a median score of 40/100 and 20 countries under the 50 point divide, the Index highlights a dramatic dearth of life-saving harm reduction services across the world. The level of investment in harm reduction is considered as adequate in only 5 out of the 30 countries. While harm reduction interventions are nominally present in most of the surveyed states, the Index shows an alarming lack of availability and coverage across the board.

The country scored zero for having harm reduction funding, zero for harm reduction intervention availability and coverage and scored 8 out of 100 for equity of access to harm reduction services.

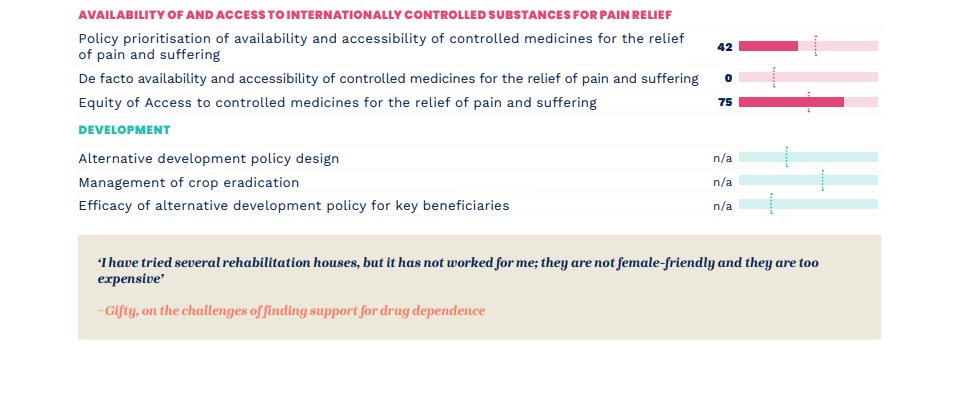

Ghana was scored 32 out of 100 in the area of access to medicines.

This covered policy prioritization of availability and accessibility of controlled medicines for the relief of pain and suffering which scored 42 out of 100. This is because there is explicit provision that establishes government’s obligation to make adequate provision to ensure the availability of controlled medicines for the relief of pain and sufferings.

But there is no approved national medicine policy plan that recognizes the importance of the availability and accessibility of controlled medicines for the relief of pain and sufferings. It recorded 75 out of 100 in equity of access to controlled medicines for the relief of pain and sufferings.

The last indicator which is development was not applicable in the Ghanaian context so it had no score there. This area however covered whether there are alternative or sustainable development programmes to provide alternatives to the cultivation of crops used for illegal drug production. That is to what extent local communities, participants and indigenous and minority groups were meaningfully included in the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of alternative development policies and programmes.

Other details

Norway, New Zealand, Portugal, the UK and Australia are the five leading countries on the global ranking.

However, Norway, despite topping the Index, still only managed a score of 74/100. And the median score across all 30 countries and dimensions is just 48/100.

“48 out of 100 is a drug policy fail in anyone’s book,” said Ann Fordham, Executive Director of the International Drug Policy Consortium which led on the development of the Index with the partners in the Harm Reduction Consortium.

She continued that, “None of the countries assessed should feel good about their score on drug policy, because no country has reached a perfect score. Or anywhere near it. This Index highlights the huge room for improvement across the board.”

For decades, tracking how well - or badly - governments are doing in drug policy has been an elusive endeavour. In no small part, this is because data collection efforts by both governments and the UN have been driven by the outdated and harmful goal of achieving a ‘drug-free society.’

Most governments continue to employ a repressive approach to drug control based on this skewed data, which in turns means they cannot be held accountable for the damage their policies inflict on the lives of so many people.

The success of drug policies has not been measured against health, development, and human rights outcomes, but instead has tended to prioritise indicators such as the numbers of people arrested or imprisoned for drug offences, the amount of drugs seized, or the number of hectares of drug crops eradicated.

What is the Global Drug Policy Index?

The Global Drug Policy Index is the first-ever data-driven global analysis of drug policies and their implementation.

It is composed of 75 indicators running across five broad dimensions of drug policy: criminal justice, extreme responses, health and harm reduction, access to internationally controlled medicines, and development.

Chair of the Global Commission on Drug Policy (former Prime Minister of New Zealand), Helen Clark, said the Global Drug Policy Index is nothing short of a radical innovation.

“Good, accurate data is power, and it can help us end the `war on drugs´ sooner rather than later.”

Former Director of the Prison System of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Julita Lemgruber said, “What’s clear from the results is that no government can be complacent. Even in the highest-ranking countries, progress is sorely needed. Governments worldwide must abandon the idea of drug policies as instruments of “war” and understand them as means to promote human rights and citizenship.”

The Index’s Results

The Index’s results reflect that:

The militarised and law enforcement approach to drug control continues to prevail. This means some level of lethal use of force by military or police forces was reported in half of the countries surveyed, with widespread cases in Mexico and Brazil.

It revealed that the disproportionate impact of drug control on marginalised people on the basis of gender, ethnicity and socio-economic status was reported to some extent across all dimensions, and across all countries.

Drug law enforcement targets primarily nonviolent offences, and especially people who use drugs: Only 8 out of the 30 countries surveyed have decriminalised drug use and possession, and out of those, only 3 managed to truly divert people away from the criminal justice system.

The funding gap for harm reduction remains highly concerning: Only 5 out of 30 countries have allocated ‘adequate’ funding to harm reduction, and of those countries, funding is considered secure in only one (Norway).

There is a huge gap between government policies and their implementation on ensuring access to controlled medicines, especially in countries like India, Indonesia, Mexico, and Senegal which score high on policy, but score 0/100 for actual availability for those in need.

Alternative development programmes in areas of illegal cultivation remains entrenched in interdiction and eradication, with Colombia scoring particularly low (23/100) due to its militarised strategy focusing on forced eradication and the harmful use of aerial spraying.

Policy recommendations

What would a perfect score look like?

The absence of extreme sentencing and responses

- The country has abolished the death penalty, including for drug offences. All existing death sentences for drug offences have been reviewed and commuted.

- The country has taken appropriate measures to ensure that no extrajudicial killings are committed in connection to drug control, either by law enforcement agents, the military or non-state actors.

- Military and special security forces are excluded from all tasks pertaining to the enforcement of drug laws.

- National drug laws do not allow for life imprisonment as a possible sanction for any drug offence. All existing life sentences for drug-related offences are reviewed and commuted.

- No person is held against their will in state-run or private drug ‘treatment’ centres. Access to inpatient drug treatment is always voluntary.

The proportionality of the criminal justice response

- There are no reported cases of violence or torture by the police, or arbitrary arrests and detention. All elements of a fair trial14 are respected.

- Criminal justice responses related to drug control do not disproportionately impact people on the basis of their ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation or socio-economic status.

- The country’s drug laws or legal frameworks do not include mandatory minimum sentencing or pretrial detention for drug offences.

- There are provisions in national legislation or in official national policy documents for the decriminalisation of all drug use and possession for personal use. Where administrative sanctions are applied, these are proportionate and non-intrusive.

- Decriminalisation has led to a dramatic reduction in the number of people who use drugs in contact with the criminal justice system.

- There are also provisions in national laws and policies for alternatives to arrest, prosecution, conviction and/or punishment for drug offences. Alternatives exist at the point of initial contact with law enforcement, before conviction and at sentencing. They include a range of treatment and care options adapted to the needs and preferences of people dependent on drugs caught in the criminal justice system. Failure to attend or complete treatment, or restarting/continuing the use of drugs, does not result in punishment.

- People are never, or very rarely, imprisoned for non-violent drug offences, and make up less than 5% of the prison population.

Health and harm reduction

- There are explicit supportive references to harm reduction in national policy documents.

- Funding for harm reduction is considered to be adequate and sustainable.

- People who use drugs have adequate access to key harm reduction interventions such as NSPs, OAT, take-home naloxone, drug consumption rooms and drug checking services, both in the community and in prison.

- There are no disparities in access to harm reduction services on grounds of ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation or socio-economic status.

Availability of, and access to, internationally controlled substances for the relief of pain and suffering

- There are explicit provisions in national legislation, policy documents and regulatory instruments that establish the country’s obligation to ensure adequate availability of controlled medicines.

- There is an approved national medicines strategy that recognises the importance of availability and accessibility for controlled medicines.

- The policy-making process relating to controlled medicines meaningfully involves key stakeholders, such as medical boards, health professionals, patients, and patients’ representatives.

- Opioid medicines are available to all those in need for the relief of pain and suffering.

- There are no disparities in access to controlled medicines based on geographical location, gender, ethnicity and socio-economic status, or for people who use drugs.

Development

- Alternative development policies are embedded within a broader development strategy that does not operate within a militarised or security framework, placing emphasis instead on environment protection, and the empowerment of women, youth and low-income groups.

- Alternative development programmes do not include provisions for forced eradication and/or the use of aerial spraying. They should allow for adequate sequencing to ensure that targeted households have sustainable livelihoods in place prior to any crop eradication effort.

- Local communities, minority and indigenous groups are meaningfully involved in the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of alternative development programmes.

Methodology

The Global Drug Policy Index was developed through a complex process including consultations, identification of indicators, thematic policy clusters and dimensions, data collection and analysis. The data was compiled through desk-based research and a comprehensive civil society survey.

Each indicator, policy cluster and dimension were then weighted against one another to achieve a final country score ranging from 1 to 100.

The Global Drug Policy Index is a project of the Harm Reduction Consortium, which includes the following partners: the European Network of People Who Use Drugs (EuroNPUD), the Eurasian Harm Reduction Association (EHRA), the Eurasian Network of People who Use Drugs (ENPUD), the Global Drug Policy Observatory (GDPO) / Swansea University, Harm Reduction International (HRI), and the International Drug Policy Consortium (IDPC).

The rest include the Middle East and North Africa Harm Reduction Association (MENAHRA), the West African Drug Policy Network (WADPN), the Women and Harm Reduction International Network (WHRIN), and Youth RISE.

Latest Stories

-

Meghan Netflix show delayed over LA wildfires

22 minutes -

Kwesi Nyantakyi: How the new Sports & Recreation Ministry can transform the Youth

3 hours -

Barca fights back to beat Real Madrid 5-2 for Spanish Super Cup success

4 hours -

Photos: Mahama joins National Prayer and Thanksgiving Service

4 hours -

Mahama reaffirms commitment to education reform, tackles immediate feeding challenges in SHSs

5 hours -

Vetting of ministerial nominees begins on Monday, January 13

5 hours -

Ghanaian, Prof Wisdom Tettey is Carleton University’s 17th President and Vice-Chancellor in Canada

5 hours -

National Cathedral can be built at a reasonable cost without state funds – Mahama

6 hours -

13-year-old girl survives alleged ritual murder attempt in Eastern Region

6 hours -

Anti-corruption campaigner lauds ORAL, commends Mahama

6 hours -

Türkish Ambassador to Ghana congratulates Vice President Opoku-Agyemang

6 hours -

GUTA dissociates itself from its president’s comment urging gov’t to retain E-levy

6 hours -

My victory is the manifestation of the will of God, says Mahama

6 hours -

We’ll strengthen the fight against corruption – Mahama

6 hours -

National Cathedral project expenditure to be probed soon – Mahama

7 hours