A Research Paper by Dr. Richmond Atuahene (Banking Consultant), Isaac Kofi Agyei (Data & Research Analyst) and K.B Asante (Chartered Certified Accountant)

First, here are the research findings:

Research findings and discussion on the effect of the public debt crisis on Ghana's economy

1. Ghana’s public debt crisis has affected the economy through multiple channels. First, the public debt crisis, especially the sovereign debt default in December 2022, led to the exclusion of the country from international capital markets with its adverse effects on international trade finance and payment system as well as foreign direct investment.

The public debt crisis negatively impacted the banking sector and the economy at large. Banks and other financial institutions were major holders of government bonds which did impact negatively on their balance sheets and financial stability was put at risk as the government decided to restructure their assets of medium maturity with a long-term maturity period. Other channels may also be at work and feedback-loop effects may take place.

Sovereign debt crises were also accompanied by a currency crisis and caused a deterioration in businesses’ and households’ confidence. Furthermore, measures of fiscal consolidation that were typically taken to restore confidence in the long-run sustainability of public debt led to short-run negative effects on the economy, and thus unintentionally exacerbated the crisis.

Furthermore, banking crises are usually resolved through the injection of fresh capital by the national governments through the Financial Stability Fund and thus the problems in the banking sector may end up as a further liability for the government. While a sovereign debt crisis led through multiple channels simultaneously – thus making the chronological reconstruction of the events – the outcome is a contraction in output, a loss in the number of employees, a weaker financial system, and, more generally, a decline in living standards.

2. Despite the domestic debt reduction in the form of debt exchange, the Ghanaian economy has slowed down and restrained economic growth and development through two channels including—"debt overhang,” and “crowding out” which has also increased crisis risk thus making the economy vulnerable to abrupt changes in market sentiment, jeopardizing both stability and future economic growth. The results of this study also found that domestic debt reduction through domestic exchange has continued to hamper economic growth.

Heavy public debt service obligations resulted in a large risk premium on interest rates, periodic bouts of financial market instability, and a crowding out of bank credit to the private sector, all of which had contributed to a very low potential growth rate. For Ghana’s domestic debt reduction to be successful, must be mainly driven by decisive and lasting (rather than timid and short-lived) fiscal consolidation efforts focused on the reduction of government expenditure, in particular, cuts in social benefits, government flagship programs and conscious reduction of public sector wages and compensation, without any fiscal consolidation.

3. Ghana must ensure that there is robust real GDP growth in terms of lower inflation in the next five years to increase the likelihood of a major debt reduction so that it could help the country “grow their way out” of indebtedness”. Third, high debt servicing costs play a disciplinary role strengthened by market forces and require the government to set up credible plans to stop and reverse the increasing debt ratios. Debt reduction has increased uncertainty and reduced investor confidence in the Ghanaian economy and its policies which could also reduce economic growth. Debt restructuring will be a prerequisite but not enough to restore its sustainability.

To reduce public debt to 55% of GDP by 2028, it will also be necessary to continue the ambitious fiscal consolidation strategy and structural reforms set by the IMF, namely an adjustment of 5.1% of GDP over the 2023-2026 period. While we conclude that there was a reduction in the net present value of debt servicing costs does not mean that more money is available now for Ghana to spend. The reduction meant that future debt servicing costs were reduced compared to the current baseline during the next decades and, therefore, Ghana would have to spend less on financing its debt in the future.

The World Bank recently noted that Ghana remained stuck in a debt trap with no hope of escaping anytime soon. However, the country is still in a debt trap with Eurobond holders’ values of US$ 13.6 billion which could be best described as a debt overhang.

First, domestic debt exchange in the medium to long term tends to reduce uncertainty and affects the market confidence in the country and its policies, thus plummeting future economic growth, however, debt reduction has reduced capital inflows which has weakened confidence in the government structural reforms and the new policies introduced recently. On the positive, the country’s successful completion could be an endorsement by the international community including the IMF, World Bank, and other international donors that the country is pursuing sound macroeconomic policies and structural reforms. The country’s default on the international capital market has prolonged the time that Ghana could facilitate early access to the international financial markets.

4. The country’s sovereign restructuring episode has harmed the financial sector of the country for several reasons. First, the asset side of banks’ balance sheets has taken a direct hit from the loss of value of the restructured assets, such as sovereign bonds. Second, on the liability side, banks have experienced the interruption of interbank credit lines. These issues have negatively affected their ability to mobilize resources at times of stress.

Finally, restructuring episodes have also triggered interest rate hikes, thereby increasing the cost of banks’ funding and affecting their income positions. Together, these factors impaired the financial position of domestic institutions to such a degree that financial stability has been threatened and pressures for bank recapitalization and official sector bailouts have increased.

A final observation is that debt restructuring in Ghana has had cross-border implications. Nigerian and South African banks and financial institutions were exposed to sovereign risks in Ghana that underwent restructuring transmitted the shock across borders, either directly by loss of value of government securities or indirectly through their exposure to the banking sector of that country.

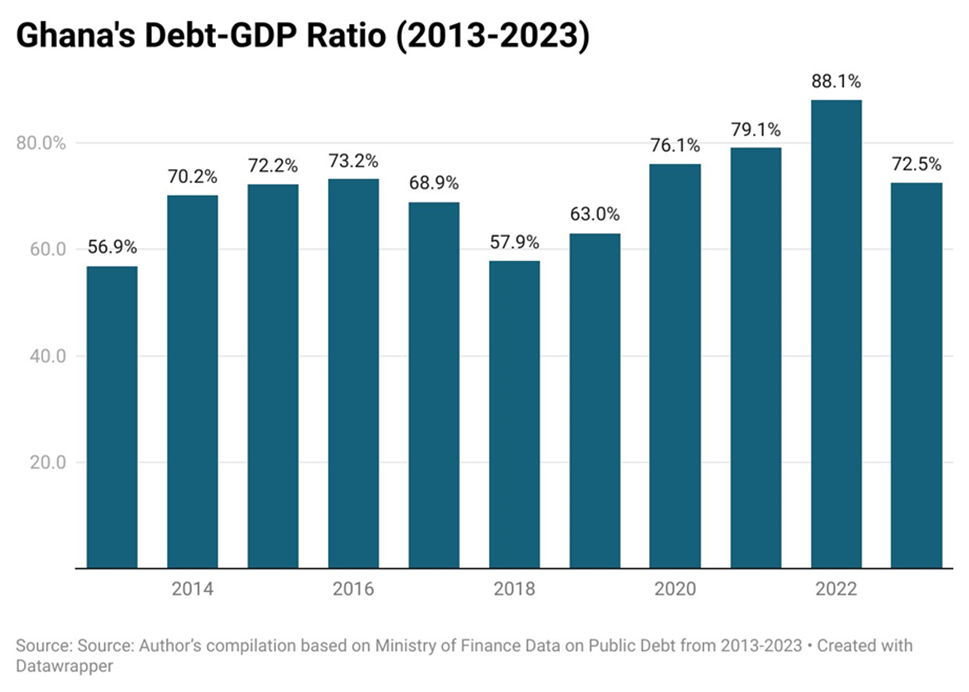

5. The successful debt reduction operation has not appreciably reduced the level of the country’s cost of debt servicing, thereby increasing the “fiscal space” available to Ghana. Crucially, the completed DDEP has also produced a very large cash debt relief for the government of almost GHS 61.7 billion in 2023, relieving pressure on the domestic financing market, but despite the domestic debt exchange, domestic debt has increased by GHC 54.3 billion to GHC 259.7 billion in December 2023.

Debt reduction has created fiscal space which means the availability of additional resources that can be used in desirable government spending (or tax reduction). The fiscal space is used to enhance medium-term growth and finance this growth from future fiscal revenue. In fact, there are different channels through which a county can create or enlarge its fiscal space.

6. Also, despite the successful implementation of the domestic debt exchange, one negative effect of domestic debt reduction has caused investors to lose confidence in the country's secondary bond market and the ability to repay its debt on time. This has led to a decrease in domestic investment and an increase in the cost of borrowing for the government and local businesses. The decreased domestic investment has a ripple effect on the local economy.

As businesses including SMEs have struggled to access the funds they need to grow and hire workers, the unemployment rate in Ghana has dramatically increased. This lack of investment has also led to an increase in the cost of borrowing for the government and local businesses, making it more difficult for them to finance their operations and invest in growth. In terms of the effects on the domestic bond market and local financial institutions (banks, insurance, asset management companies & pension scheme agencies), domestic debt exchange had both direct and indirect effects. The direct effect was that the restructuring resulted in a loss of value for domestic bondholders. This has led to a decrease in demand for Ghana government bonds and a decrease in the overall value of the bond market.

The indirect effect was that the restructured domestic debt has affected the stability of local financial institutions, especially in the area of liquidity and solvency. If the government was unable to manage its domestic debt exchange process properly, the economy would suffer as a result, local banks would face increased risks and potentially experience financial difficulties.

This has led to a decrease in the availability of credit for local businesses as well as higher costs of credit and households, thus hindering economic recovery and growth. Ghana’s balance of payments is expected to continue to deteriorate further in 2024, on the back of continued capital outflows, and the continued Cedi depreciation because of a decline in inward remittances, low returns on extractive industries like gold, and poor cocoa syndication loans of US $ 800 million lowest recorded over the past two decades.

7. Debt reduction has caused considerable reputational damage, market exclusions, higher borrowing costs, sanctions, and trade embargo, (sovereign assets outside the country) are examples of costs that a debtor country might suffer in case of default. The country has not had access to international capital markets for at least four years thus affecting foreign direct investment. Most correspondent banks of the Ghanaian banks overseas withdrew their credit lines when the country was downgraded by the credit rating agencies as well and the country defaulted in the payment of external debt in December 2022.

Reputational costs include market exclusion and increased borrowing costs for the country. creditors might refuse to purchase the debtor country’s bonds following debt restructuring. Future Creditors impose this punishment on the debtor country like Ghana. Creditors might purchase the debtor country’s bonds following debt restructuring but request a premium (i.e. a higher interest rate to compensate for the risk of future default or other restructuring).

The recent inability of the cocoa board and the government to pay some holders of cocoa bills who did not participate in the Cocoa Bills Exchange program showed how the government is bankrupt, and investors have lost confidence in the investment climate. The DDEP has had a significant impact on investor confidence in the fixed-income market in Ghana. The sudden loss of value for existing bondholders has led to concerns about the safety of government-issued securities and has shaken investor confidence.

Investors who previously considered government-issued securities as risk-free investments may now be more cautious and may require a more thorough assessment of risks before investing in fixed-income securities. The decline in investor confidence may also have broader implications for the fixed-income market in Ghana. Reduced demand for government-issued securities may lead to higher borrowing costs for the government, as they may need to offer higher coupon rates to attract investors. This could increase the cost of debt servicing for the government and impact the country's overall fiscal management. Additionally, lower investor confidence may also result in reduced liquidity in the fixed-income market, as investors may be hesitant to buy or sell securities, further affecting market dynamics.

8. The domestic debt exchange (debt reduction) impacted negatively domestic banks and non-banking financial institutions on solvency, regulatory capital requirements, and their loanable funds and adversely affected the economic and financial livelihood of Ghanaians, especially the pensioners, poor and vulnerable in the society whose incomes have been whittled away by the higher inflation.

Domestic debt exchange through debt reduction which included principal haircut and coupon rate reduction has triggered a decline in domestic investors’ confidence in governments’ creditworthiness and raised doubts about the sustainability of government finances. As the country has reduced the value of its bonds, the domestic banks have had a marginal reduction in the number of assets on their balance sheet and possibly insolvency.

Due to the growing interconnectedness of the country’s financial system, a bank failure couldn’t happen in a vacuum. Instead, there is the possibility that a series of bank failures could spiral into a more destructive ‘contagion’ or domino effect’. Ghana’s debt reduction has already affected capital spending and recurrent spending other than wages and transfers have been cut to levels that hamper potential growth and the provision of basic public services. On the revenue side, an increase in already high tax rates levied on narrow bases has contributed to a dramatic further deterioration in already low current tax collection rates.

9. The domestic debt reduction has also created a situation known as an inverted yield curve. An inverted yield curve occurred as short-term interest rates on Treasury bills were being quoted between 22% and 33.7% per annum exceeding long-term rates on Government bonds’ coupon rate of 9.1% or 8.51% per annum. The term yield curve refers to the relationship between the short- and long-term interest rates of fixed-income securities issued by the Ghana Government Treasury.

The yield curve has inverted—meaning short-term interest rates moved higher than long-term rates—and could stay inverted through 2023 and 2024. This has signaled an imminent recession or slowdown in the Ghanaian economy. An inverted yield curve is when shorter-term notes pay higher effective yields than longer-term bonds. The yield curve is considered “normal” when longer-term bonds yield more than shorter-term ones. In the post-DDEP era, the government has been borrowing at the money market at the rate between 22% and 33.7% while the government bond coupon rate is quoted at 9.1% per annum. The inverted yield curve has been viewed as an indicator of a pending economic recession in the country.

When short-term interest rates exceed long-term rates, market sentiment suggests that the long-term outlook is poor and that the yields offered by long-term fixed income will continue to fall. The existing bond market was considered a major prerequisite to sustainable debt dynamics as well as improved growth prospects by the financial sector and the wider public. However, the DDEP has not managed to lower signal rates during the post-DDEP era, as the market interest rates on short-term government bills have risen to historically high levels and thus created an inverted yield curve and remained unstable.

10. Domestic debt reduction could have lasting effects on the country’s economic growth, and confidence in the domestic market and the financial sector. Following the domestic debt exchange, universal banks with large exposures to government bonds have experienced a deterioration in their balance sheets, thus reducing the supply of loans to firms via a traditional bank lending channel (Gennaioli et al. (2014) and Acharya et al. (2014b). Furthermore, the weakened financial sector has impaired financial intermediation thus leading to a hesitance of financial institutions to provide funds to individuals and businesses as well as poor low savings culture.

This would then threaten future economic growth and development. Indeed, the present economic challenges may compromise the ability of individuals and businesses to pay their loans which would heighten the impairment levels. According to the Bank of Ghana, MPC March report 2024 on the banking sector NPLs stood at 24 percent of total loans thereby creating systemic banking crises that could be highly disruptive events that could lead to sustained declines in economic activity, financial intermediation, and ultimately in welfare ( Laeven and Valencia, 2018).

Both the Ghana budget and its debt might seem well manageable in the coming years. However, the debt trap caused a long shadow, thus causing lingering challenges and risks. Future higher interest rates, budgetary pressure, and weak growth can lead to a higher debt-servicing burden and refinancing needs. Keeping up fiscal strength and, first and foremost, promoting growth, are the best ways for Greece to address these challenges.

11. The debt reduction has caused serious collateral damage as well as a loss of market confidence in the Ghanaian economy. Debt exchange has caused reputational damage as Cocoa Board Market Ltd was unable to raise financing for the 2023/2024 cocoa season purchase in September/October 2023. Ghana’s cocoa output target of 830,000 metric tonnes was delayed as the International Financiers' Cocoa Board rated it as a higher-risk institution and Ghana as a higher-risk country for which international financiers demanded a higher premium. Ghana signed the costliest syndication loan ever for cocoa because of the country’s debt crisis.

According to Bloomberg Cocoa Board received the funding at an interest rate of almost 8% per annum. Ghana secured its annual loan to pay for cocoa purchases at the highest interest rate on record, following this year’s debt restructuring of the West African nation’s obligations that ruined investor appeal. International banks have pledged to lend industry regulator Ghana Cocoa Board $800 million for cocoa purchase from farmers at almost 8% per annum with the terms of the deal. It is the costliest syndicated facility the board has received since the annual loans started in 1992-93, the people said, asking not to be identified because the transaction isn’t yet public. The board, also known as the Cocoa Board, has previously obtained loans from investors at better rates than the government at an average rate of 2%.

In 2023, the negotiations have been complicated by the country’s debt restructuring that was needed to unlock a $3 billion government bailout from the International Monetary Fund. The country’s default for both domestic and external debt in 2022 has caused collateral damage on other institutions – contagion –changes the interpretation of default costs but does not change the answer; except for one key complication: it implies that there may be a second instrument – transfers across institutions – as an alternative to default. The recent inability of the government and the Cocoa Board to settle some of the holders who did not participate in the Ghana Cocoa Bill Exchange program has caused massive collateral damage to the credibility of both the government and the Cocoa Board.

12. The study has identified both direct and indirect channels through which a large country’s external debt has affected productive investment negatively. The debt overhang has reduced the incentive to invest in Ghana as a result of higher domestic real interest rates due to impaired access to the international capital market after the country defaulted on domestic and external debt in December 2022; and also, as a result of low profitability due to economic downturn in 2022 and the decreased in public investment that was complementary to private investment.

13. Ghana is still experiencing debt overhang as the country’s debt burden in the power sector is so large that in post domestic debt restructuring era, the power sector providers cannot take on additional debt to finance future projects or pay off the existing debt to the power generation companies in the energy sector. The domestic debt reduction has not addressed the debt overhang for the power sector arrears or the legacy debt. According to IMF Country Report No. (19/367) posited that power sector arrears were about US$2.7 billion in late 2018, of which US$800 million was owed to private fuel suppliers and independent power plants (IPPs).

For 2019, the authorities project the financing shortfall for the sector to be at least US$1 billion (1.5 percent of GDP), which they plan to partially finance off-budget. Partial payment arrangements may be insufficient to stave off more formal approaches by IPPs to collect amounts due. Absent measures to address the sector’s financial problems, the accumulated cost to the government, including current arrears, could reach US$12.5 billion by 2023. The burden is so large that all earnings pay off existing debt rather than fund new investment projects, making the potential for defaulting higher. The findings confirmed that debt overhang has led to under-investment in the Ghanaian energy sector.

For example, most of the firms in the energy sector are in financial distress and it is difficult to pay off their suppliers or raise funds for new investments because the proceeds from these new investments mostly serve to increase the value of the existing debt instead of new investments. Debt overhang has caused under-investment problems in the energy sector that could impact negatively on future production and supply of electricity to the entire country.

Debt overhang could be alleviated if the various creditors like WAPCo, Sunon Asogli Power Co. Ltd, Bui Power Authority, and the Government of Ghana manage to renegotiate their contracts and restructure the balance sheets. The debt overhang is also currently being experienced by Bui Power Authority because of the inability of the Electricity Company of Ghana to pay for power supplied and this could cause underinvestment by the various power generators in the country. ECG (and the central government) are counterparties to several take-or-pay contracts with independent power producers. The contracts require payment for contracted volumes of electricity even if the electricity is not consumed (take-or-pay charges).

When ECG expenses the charge, its equity is reduced, and its liabilities (accounts payable) increase. The reduction in equity lowers the value of the government’s investment in ECG. The actual payment of the claim by ECG or the government does not alter the public sector’s net worth. The unresolved external commercial debt including that of a euro-bond worth US$13.6 billion is still creating a debt overhang in the country. From the unresolved debt overhang of IPPs. the country could experience power outages popularly known in Ghana as ‘Dumsor’ could negatively impact the country’s economic recovery.

14. Another negative effect of debt overhang is that it has caused investors to lose confidence in the government's inability to repay its local bonds on time. This has led to a decrease in local investment and an increase in the cost of borrowing for the government and local businesses with yearly treasury bill rates increasing from 22% to 33.7% post-DDEP era.

The higher interest rates on treasury bills also affect the country’s banking institutions thus creating an adverse selection problem. As interest rates rise more conservative, risk-averse borrowers shy away from the credit market. A larger proportion of the people applying for loans are thus those who are willing to take risky bets. The likelihood of default increases and so therefore does the banks’ proportion of non-performing loans.

The domestic debt exchange has resulted in the government regularly mopping liquidity from the banking sector by purchasing considerable volumes of Treasury bills at increasingly high-interest rates. The domestic debt exchange has also weakened the financial sector through impaired financial intermediation that led to a hesitance of financial institutions to provide funds to individuals and businesses.

Credit to the private sector has contracted in the third quarter of 2023 as Banks continued to deploy their resources towards treasury bills as opposed to the extension of credit facilities in response to the increased risks associated with lending due to the deteriorating macroeconomic conditions and the impact of the domestic debt exchange program thus confirming the crowding out hypothesis. This has threatened future economic growth and development. Indeed, the present economic challenges have compromised the ability of individuals and businesses to pay their loans which impacted negatively on the non-performing assets of the banking sector.

The recent Bank of Ghana report on the increases in the non-performing asset ratio from 15% in 2022 to 20% in 2023 confirmed the debt overhang hypothesis. Weaker economic activity has translated into higher non‐performing loans by both firms and households which could increase bank distress through balance sheet and liquidity effects. The 2022 currency depreciation has exacerbated non‐performing loan volumes through currency mismatches. From a citizen’s viewpoint, the numerous taxes introduced in the 2023 budget by the Government meant that high debt means higher future taxes and/or reduced social benefits – and when combined with reduced corporate activity – less employment.

15 . The country’s debt overhang has also led to stagnant growth and a degradation of living standards from reduced funds to spending in critical areas such as healthcare, education, and social care like Leap. The debt overhang had resulted in the non-payment of some road contractors as well as food suppliers to the National Food Buffer Stock Company that have resulted in higher non-performing assets of the banking sector.

The country’s banking system exhibited significant losses resulting in a share of nonperforming loans above 24 percent of total loans thus indicating that the sector was in crisis. Because of the way they affected balance sheets and bottom lines, debt overhangs have distressed entities including banking institutions in different ways. The decreased domestic investment has a rippling effect on the local economy. As businesses including SMEs have struggled to access cheaper funding to grow and expand their businesses and impeded the hiring of workers, the unemployment rate in Ghana has dramatically increased.

This lack of investment has also led to an increase in the cost of borrowing for the government and local businesses, making it more difficult for them to finance their operations and invest in growth. In post-DDEP, according to the Bank of Ghana MPC report (2024), banking sector loans and advances grew by a paltry 1.77% year-on-year to GH74.8 billion (+GH1.3 billion). Private sector credit also increased by 5% to GH68.8 billion (+GHS3.3 billion) but contracted by 14.7% to GH331.1 million in real terms.

16. As part of the country’s debt crisis, the government has introduced a myriad of taxes in 2023 and 2024 to address revenue shortfalls. Currently, Ghana with a small open economy has 27 tax handles. The country has been overburdened with nuisance taxes. The debt overhang has led to an increase in taxes towards generating adequate revenue to settle both foreign and domestic creditors, thus discouraging investments due to a sudden increase in taxes.

According to recent reports, Ghana enacted legislation for the 2024 Budget on 29 December 2023, including the Value Added Tax (Amendment) Act, 2023 (Act 1107), the Excise Duty (Amendment) (No.2) Act, 2023 (Act 1108), the Stamp Duty (Amendment) Act, 2023 (Act 1109), the Exemptions (Amendment) Act, 2023 (Act 1110), and the Income Tax (Amendment) (No.2) Act, 2023 (Act 1111).

A VAT flat rate of 5% is introduced on the following, without a deduction for input tax: the supply of a (commercial) immovable property for rental purposes, other than for accommodation in a dwelling or a commercial rental establishment; and the supply of an immovable property including land by a real estate developer; A new penalty equal to 30% of the VAT amount due is introduced for appointed VAT withholding agents that fail to withhold and remit VAT by the 15th of the following month (7% withholding on standard-rated invoices); VAT exemptions are revised, including the VAT exemption is removed for imported textbooks, exercise books, newspapers, publications, and charts (locally produced remain exempt), as well as architectural plans and similar plans, drawings, scientific and technical works, periodicals, magazines, trade catalogs, price lists, greeting cards, almanacs, calendars, diaries and stationery, and other printed matters.

A new penalty equal to 30% of the VAT amount due is introduced for appointed VAT withholding agents that fail to withhold and remit VAT by the 15th of the following month (7% withholding on standard-rated invoices); VAT exemptions are revised, including the VAT exemption is removed for imported textbooks, exercise books, newspapers, publications, and charts (locally produced remain exempt), as well as architectural plans and similar plans, drawings, scientific and technical works, periodicals, magazines, trade catalogs, price lists, greeting cards, almanacs, calendars, diaries and stationery, and other printed matters.

VAT zero-ratings are revised, including the VAT zero-rating for locally manufactured textiles by approved manufacturers the VAT zero-rating for locally manufactured textiles by approved manufacturers is extended to 31 December 2025; the VAT zero-rating for supplies of locally assembled vehicles under the Ghana Automotive Development Programme is extended to 31 December 2025; and The stamp duty rates are revised, including new fixed rates from GST 18 to GHS 896.30 and ad valorem rates of 0.25% to 0.5%; and the individual income tax brackets/rates are amended as follows: up to GHS 5,880 - 0%; over GHS 5,880 up to GHS 7,200 - 5%; over GHS 7,200 up to GHS 8,760 - 10%; over GHS 8,760 up to GHS 46,760 - 17.5%; over GHS 46,760 up to GHS 238,760 - 25%; over GHS 238,760 up to GHS 605,000 - 30%; over GHS 605,000 – 35; The measures of the amendment acts generally apply from 1 January 2024, government introduced taxation on lottery operations and winnings from lottery. The gross gaming revenue from lottery operations, including betting, gaming, and any game of chance is taxed at an income tax rate of 20%.

Payments in respect of winnings from the lottery are subject to a final withholding tax rate of 10%. vi) Increase in the upper limits of quantifiable motor vehicle benefits. The upper limit of motor vehicle benefits to be included in the employment tax computation has been increased as follows: Driver and vehicle with fuel - GHS1,500; Vehicle with fuel - GHS1,250; Vehicle only - GHS625; and Fuel only - GHS625. vii) Revision of the personal income tax bands and rates: The personal income tax bands and rates for individuals have been revised to align with the 2023 minimum daily wage. There is an introduction of an additional tax rate of 35% on income exceeding GHS600,000 per year.

Growth and Sustainability Levy, 2023 (Act 1095) Act 1095 repeals the National Fiscal Stabilization Levy, 2013 (Act 862) and introduces the Growth and Sustainability Levy (GSL or levy). The GSL is payable by entities categorized into three groups as follows: Category A- Existing National Fiscal Stabilization Levy entities plus six additional sectors: 5% of profit before tax; Category B- Mining companies and upstream oil and gas companies: 1% of gross production); and Category C- All other entities not falling within Category A or Category B: 2.5% of profit before tax.

The levy is applicable for the 2023, 2024, and 2025 years of assessment. It is payable quarterly and due on 31 March, 30 June, 30 September, and 31 December of the year. The above new taxes introduced by the government have affirmed the debt overhang hypothesis. Excessively high rates of tax exact a high cost in terms of lower private investment and growth. They reduce the incentive to invest because the after-tax returns to investors are lower. In addition, the cost of compliance with the administration of taxes can be high.

The literature shows that lower rates of tax can increase investment and growth. Higher rates of tax have decreased business entry and the growth of established firms, with the medium-sized firms hit hardest, as the small ones can trade informally, and the large ones avoid taxes, which have also resulted in the existence of some multinationals in nearby countries. As well as reducing tax rates, policies that broaden the tax base, simplify the tax structure, improve administration, and give greater autonomy to tax agencies help to reduce this constraint.

The new myriad of taxes introduced in the 2023 and 2024 budget statements has been impacting negatively on the private sector, especially the SMEs. The recent 21% value-added tax for residential customers of electricity is one of the nuisance taxes introduced in the 2024 government budget statement which imposed hardship for individuals and households in an already bad economic condition. Instead of the government improving electricity transmission losses by 30%, the government has decided to impose a 15% consumption tax this will likely affect the country’s growth targets as the move is expected to increase the the cost of operations of SMEs and slow down production and thus worsen the already bad unemployment situation in the country.

17. The country’s debt crisis has affected and discouraged private investments depending on how the government has raised the fiscal revenue necessary to finance local debt-service obligations (an inflation tax and excessive government expenditure that has contributed to increased domestic inflation that also discouraged private investment). These combined effects discouraged private investment and thus hurt national output growth. As part of domestic debt restructuring the country has experienced debt overhang which has led to the recent increase in taxes towards generating adequate revenue to settle domestic creditors, thus discouraging investments due to a sudden increase in recent taxes. Thus, an indebted country like Ghana retained only a fraction or nothing from domestic output and export revenue. This implied that the accumulation of debt has hampered economic prosperity through tax disincentives. Tax disincentive denoted debt overhang has impaired investments as potential investors foresee a possible tax increase on future income in a bid to repay the borrowed funds. Excessive taxes on production are hampering the growth and competitiveness of domestic businesses. Taxing production excessively has already affected local industries and worsened the already high unemployment situation in the country.

As such, the debt overhang theory posited that borrowed funds be well invested in productive sectors capable of generating adequate revenue for repaying the debt and financing domestic investments but that is not the case in Ghana because of higher unplanned government expenditures. In those developing economies such as Ghana with heavy indebtedness “debt overhang” was considered to have led to cause of distortion and slowing down of economic growth as the World Bank has revised Ghana’s gross domestic product growth in 2023 to 1.5% from earlier the 1.6%. Ghana’s economic growth has slowed down because it lost its pull on private investors. Additionally, servicing of debts has exhausted so much of Ghana’s revenue to the extent that the potential of returning to growth paths is abridged. The theory asserts that if there is a probability that Ghana’s future debt will be more than its repayment ability, then the anticipated cost of debt-servicing can depress the investment. However, the extent to which investment is discouraged by debt overhang depends on how the government generates resources to finance debt service obligations.

18. Debt overhang has bound the economy as is in a downturn since investment returns are low. As a result, high levels of debt have created multiple equilibria in which the profitability of investment varies with economic conditions. showed that debt overhang has distorted the level and composition of investment, with a severe problem of underinvestment for long-lived assets. A significant debt overhang effect is found, regardless of Ghana’s ability to issue additional secured debt. With the presence of debt overhang, the excess debt has acted as a distortionary tax, given that agents assume that a share of future output could be used to repay creditors and therefore decreased or postponed investment, thus hindering economic growth, debt on investment as the country faced with high default risk in future. The Ghana Investment Promotion Center (GIPC) has disclosed a financial deficit in its operations over the past two years. Foreign Direct Investment inflows to Ghana fell by 39% in 2022 to $ 1.472 billion, as greenfield projects remained flat while international project finance and Mergers and Acquisitions deals declined. Ghana also experienced a further decline in foreign direct investment as the Ghana Investment Promotion Centre (GIPC) recorded a 16 percent drop in investment projects in the first half of 2023.

19. The crowding-out effect in the public debt crisis experience seemed to be occurring as the government has been borrowing from the money market rate surged from 22% per annum in 2022 to a high of 33.7% per annum in 2023 but the one-year Treasury bill declined to 30% per annum which have affected the private sector seeking funds to expand as well as grow their businesses to expand the economy. As the government continued to borrow from the domestic market at higher prevailing rates between the pre-DDEP era of 22% per annum and 33.7% per annum post-DDEP period has caused a serious crowding out of the private sector which is said to be the engine of growth. This postulated that Ghana’s economic stability could be undermined by debt burden if debt service cost weighs down excessive public expenditures. This implied that public investments are crowding out as rising national debt obligations consume a large proportion of government revenue. The current situation where the government is currently borrowing from the short-term end of the money market through treasury bill rate has pushed from 22% last year to 33.7% in October 2023 thus crowding out the private sector to slow down the expansion and growth of Ghana’s economy.

As the government continued to waste resources through loose public expenditures such as the government flagship program as ‘one district, one factory’, the entire economy faced a resource shortage, thus preventing sufficient private-sector investment. As the crowding-out mechanism has triggered, private-sector capital accumulation has consequently become insufficient, which led to economic stagnation. The findings reveal that government borrowing from domestic banks results in more than a one-to-one crowding out of private credit in Ghana, implying then that government borrowing from banks is not the sole reason for crowding out private sector credit but that banks’ preference to invest excess liquidity in a low risk/high return investment by holding securities and treasury bills also add to this crowding out.

20. This study concludes, that the government budget deficit has crowded out private investment through its effect on interest rates. Recent trends in domestic credit showed the lazy banking hypothesis where the bulk of commercial bank lending has been to the Government treasury papers, instead of private sector credit has largely been lethargic. The deceleration in private sector growth which commenced in 2022, was initially associated with the increase in unemployment and reduced household income due to the recession. At the same time, the Government’s expansionary spending led to a surge in credit to the government to finance the deficit. This paper sets out to determine if the sustained increase in banking sector financing to the Government has impacted commercial banks’ capacity to lend to the private sector.

The theory of crowding out has suggested that as the government increased its spending, it has thus increased the demand for goods and services, which has led to the current higher interest rates and higher inflation in the country. A crowding-out has caused a rise in real interest rates in the post-DDEP era. By the crowding-out effect, a decrease in public investments had transmitted to a reduction in private investments due to the complementary of some private and public investments. In as much as extreme national debt can result in liquidity constrain by crowding out domestic investments in the debtor country; reliance on debt is a necessity for unindustrialized economies at their early stage of development since available financial resources at that phase could be inadequate to enhance the needed growth and development.

The crowding out could also impact negatively economic growth as it slowed down because Ghana has lost its pull on private investors while servicing of debts exhausts up so much of the indebted country’s revenue to the extent that the potential of returning to growth paths is abridged. The most severe negative effects of domestic debt are, however, also channeled through the financial sector. The crowding-out effect of domestic debt on private investment is a serious concern. Bank credit to the private sector has been empirically proven to be a contributor to economic growth. However, when governments borrow domestically, they use up domestic private savings that would otherwise have been available for private-sector lending.

As increasing public financing needs push up government debt yields, this has further caused a net flow of funds out of the private sector into the public sector, and this has pushed up private interest rates. In shallow financial markets, especially where domestic firms have limited access to international finance, domestic debt issuance of treasury bills could lead to both swift and severe crowding out of private lending. In most developing countries like Ghana, only large, well-established firms have access to international finance, suggesting that the burden of crowding out fell heavily on small and medium-sized enterprises and rural borrowers.

The higher interest rates on treasury bills have also affected banking institutions in Ghana thus creating an adverse selection problem. As interest rates rise more conservative, risk-averse borrowers shy away from the credit market. A larger proportion of the people applying for loans are thus those who are willing to take risky bets. The likelihood of default increased and so therefore does the banks’ proportion of non-performing loans. The philosophy behind the crowding out effects concept assumes that government debts expend a greater part of the national savings meant for investment due to an increase in demand for savings while supply remains constant, the cost of money therefore increases to make it difficult for the private sector to source funds for production which is expected to be engine of growth. The long-term evidence showed that economic stability has collectively been undermined by indicators of debt burden.

In the short run, shortages of foreign exchange reserves, revenue inadequacy, and unstable exchange rates had adverse and significant impacts on the real GDP growth rate. Thus, it was concluded that excessive borrowing on the money market by the government has deprived Ghana of the revenue and reserves required to fund domestic investments and enhance economic stability.

In sum, the confirmation of the lazy bank hypothesis together with the growing government deficit financed mainly from the banking sector poses a few momentous challenges in Ghana with short-run and long-run ramifications. Besides the apparent adverse effect of the observed unsustainable government deficit, this paper has uncovered another serious channel coming from the financial sector, or more precisely the banking sector. As the government issues more debt instruments (ie Treasury Bills) to finance its deficit, banks tempted by the risk-free high return motive shift their portfolio away from risky private loans and opt for lazy behavior characterized by a shrinking overall credit tilted more and more toward government debt-instruments.

This behavior not only limits their exposure toward the private sector, hence reducing private investment, but also affects adversely investment and hence overall growth potential in the future. Also, from the banking sector perspective, although lending to the government has a positive impact on banks’ profitability, it distorts banks’ incentives and the process of financial deepening since banks earning relatively risk-free returns from the government have little incentive to develop the banking market. This double-edged sword is fatal to the stance of the economy, especially in a period of rather gradual economic recovery.

21. The social implications of the public debt crisis, meanwhile, have been exceptionally severe. Ghana has suffered from a rapid increase in poverty; there has been a decline in quality primary health care; quality primary and secondary education have faced cuts in resources. The contraction of output has also led to a collapse of small and medium enterprises, while at the same time, taxation on SMEs has increased substantially. A report released by the World Bank has revealed that high inflation rates in 2022 pushed an overwhelming 850,000 Ghanaians into poverty.

The report indicated that the severe economic crisis in 2022 characterized by soaring inflation rates had devastating consequences on food security and poverty in the country. According to the World Bank country’s “international poverty” rate was estimated at 27% in 2022, an increase of 2.2% points since 2021. Ghanaian households have been under pressure from rising prices in utilities, persistent depreciation of the local currency against all major trading currencies, high inflation, and slowing down economic activities. Poverty has been projected to worsen between 2023 and 2025, increasing to nearly 34% (international poverty line) by 2025, consistent with a muted outlook on growth in services and agriculture and rising prices which are outpacing the income growth of those at the bottom of the distribution.

Poverty has many dimensions and is characterized by low income, malnutrition, ill health, illiteracy, and insecurity, among others. The impact of the different factors could combine to keep households, and sometimes whole communities, in abject poverty. (World Bank report (2023 on Ghana’s poverty levels).

22. The domestic debt reduction has impacted negatively on the Bank of Ghana’s balance sheet and its solvency as it took the biggest hit of NPV losses of GHS 37.6 billion. The NPV losses of GHS 37.6 billion in the revised domestic debt exchange on the Bank of Ghana could impact negatively on the functioning of the central bank. The Bank of Ghana may be able to continue its monetary policy and regulatory functions despite the debt restructuring.

However, the Bank of Ghana’s ability to be able to continue its other functions, such as operating payment systems, providing emergency liquidity support for the banking system, or conducting its corresponding banking operations could be compromised. Depending on its ex-ante equity position, any losses on the central bank balance sheet that may result from the DDEP would have to be addressed, including through recapitalization (Liu, Y; Savastano, M & Zettelmeyer, J. 2021).

Another finding revealed the negative effect of the revised DDEP has shifted the massive previous NPV losses (GHS30.7 billion) of the banking sector to Bank of Ghana’s NPV losses of GHS 37.6 billion, in the revised DDEP which has thus reduced the central bank’s ability to (i) manage liquidity in the banking system through open market operations and emergency liquidity support ; (ii) define and implement collateral policy given the decline in the stock of available government securities; and (iii) hold government securities as counterpart to central bank liabilities, such as currency in circulation and commercial bank deposits with the central bank. In the case of the Bank of Ghana, a recapitalization of the central bank by the government (to compensate for the losses from haircuts on its holdings of government securities) may be unavoidable. Bank of Ghana’s liquidity facilities were designed to provide emergency support to banking institutions affected by DDEP and have been key elements of the financial safety net in the recent episode.

A liquidity backstop served as a lifeline for banking institutions that might lose access to market or deposit funding. It could be especially useful for a banking system with a high degree of interconnectedness and for financial institutions that otherwise do not have access to the Bank of Ghana window for liquidity support. Collateral eligibility requirements for Repos might need to be reviewed, especially as banks faced marginal haircuts on government bonds typically used as collateral for central bank operations. In countries such as Ghana where the financial market is not well developed, however, the size and scope of liquidity backstop facilities would be limited.

IMF country report (23/168) noted that the Bank of Ghana’s Balancece sheet has been impaired by the NPV losses of GHS 37.6 billion because of domestic debt restructuring, the Government and Bank of Ghana would have to assess the impact and develop plans for its recapitalization with IMF technical assistance support. It can be inferred from this study that the public debt crisis harmed economic stability in consonance with the debt overhang, crowding out, and debt reduction effects. In an environment of limited fiscal space by the government, the risk of crowding out of the private sector by the government is real.

The recent evidence on the money market (upswing of the Treasury bill rates from 22% in 2022 to 33.7% in late 2023) has validated the crowding out hypothesis. This might lead to lower projected economic growth, further leading to lower tax collection. Thus, policymakers should ensure that public debt is used to finance high-income generating investments capable of attracting adequate revenue required to amortize the debt and create future streams of revenue that would help reduce the national debt and enhance future economic growth.

They suggested that even if it can be inferred from this study that recent domestic debt restructuring hurts economic stability in consonance with the debt overhang and crowding-out effect structural adjustment programs are put in place by governments of these countries, adverse effects can still be felt on development of general economic performance. Therefore, to accelerate economic growth, developing countries like Ghana must adopt policies that are likely to result in a reduction in the debt burden, reduce the country’s debt overhang and crowding out, and also at least ensure that the rising debt burden does not reach an unsustainable level.

READ FULL REPORT BELOW

Abstract

The present paper examines the issue of Ghana’s public debt crisis, its underlying causes, and lessons for the present and the future. After providing a historical discussion, we show that the austerity of the last four years has been unsuccessful in stabilizing the debt while, at the same time, it has taken a heavy toll on the economy and society. The IMF country report (2022) showed that the public debt was unsustainable as the total public debt stock at the end of 2022 amounted to GH₵546.15 billion, which constituted 88.1% of GDP (105% of GDP with inclusion of key SOEs and allied debts) with debt service to revenue reaching 117% and clearly that public debt was unsustainable; therefore, that the government argued that a bold restructuring of the debt was needed for the Ghana economy to reignite its engine of growth. An insistence on the current policies is not justifiable either on pragmatic or moral or any other grounds. The experience of Ghana in the early HIPC/MDRI period provides some useful hints for the way forward. A solution to the public debt problem is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the solution of current Ghana’s public debt crisis.

Ghana’s high debt meant that a significant proportion of convertible currency was consumed by debt thereby limiting the countries to import goods and services in 2022/2023. Debt service also constituted a considerable share of the budget and so imposed significant constraints on domestic investment. In December 2022, the government defaulted on both domestic and external debt payments, and out of the debt crisis, the government and IMF called for debt sustainability through debt restructuring. The domestic debt exchange (DDE) program, where the stock of the Government of Ghana's debt was to be halved from 105 percent of GDP (including contingent liabilities) to 55 percent of GDP by 2028 was launched, starting with the domestic debt exchange. The result shows excessive public debt had negatively affected the confidence of local investors in the government bonds, and any restructuring of external debt has already caused reputational on the economy and has also depressed foreign direct investment and other foreign capital inflows into the country including international cocoa syndicated loans for 2023/2024.

Another area concern of the public debt is that 2024 happens to be an election year and where Ghana has been noted for some expenditure escalations during an election year. The government must ensure that there are no up-tick unbudgeted expenditures in the upcoming 2024 elections, which could derail the fiscal consolidation. Measures by the government should be tailored towards improving economic recovery by designing policies that will reduce the burden of debt accumulation and reduce the cost of public debt servicing through robust fiscal consolidation.

This could be done in the medium term by enshrining a debt limit or debt cap of 50% of GDP in Ghana’s 1992 constitution to put a brake on unproductive borrowing, improving domestic revenue mobilization, for example instituting adequate property taxes through digitalization, enhancing the debt management process and transparency; avoid excessive borrowing from both domestic and external sources; fiscal consolidation through aggressive public expenditure cuts, limiting public sector wages and compensation increases which constituted the biggest line of expenditures (GH₵44 billion and GH₵66 billion) in both 2023 and 2024 government budget statements respectively, and also the country must make a conscious effort to reduce the endemic corruption which impact on public debt and improving efficiency in funds utilization. A wider agenda that deals with the malaises of Ghana’s economy and the structural imbalance of the country is of vital importance.

Introduction/ Background

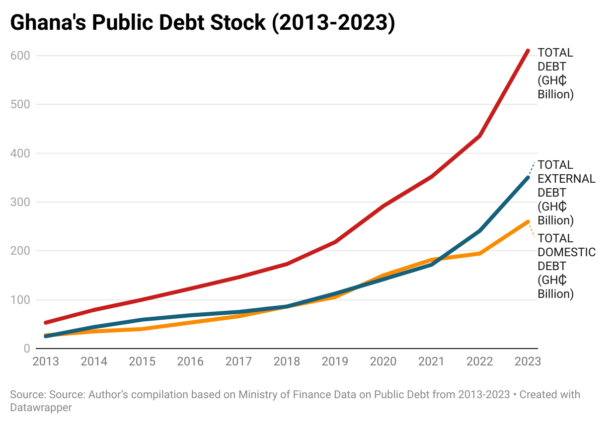

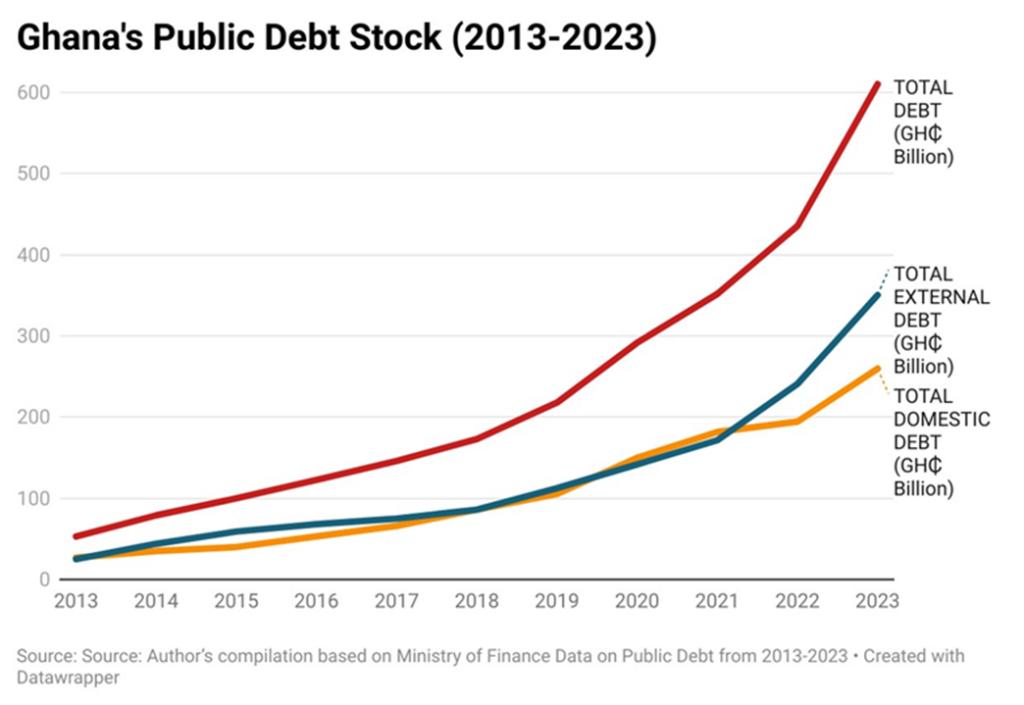

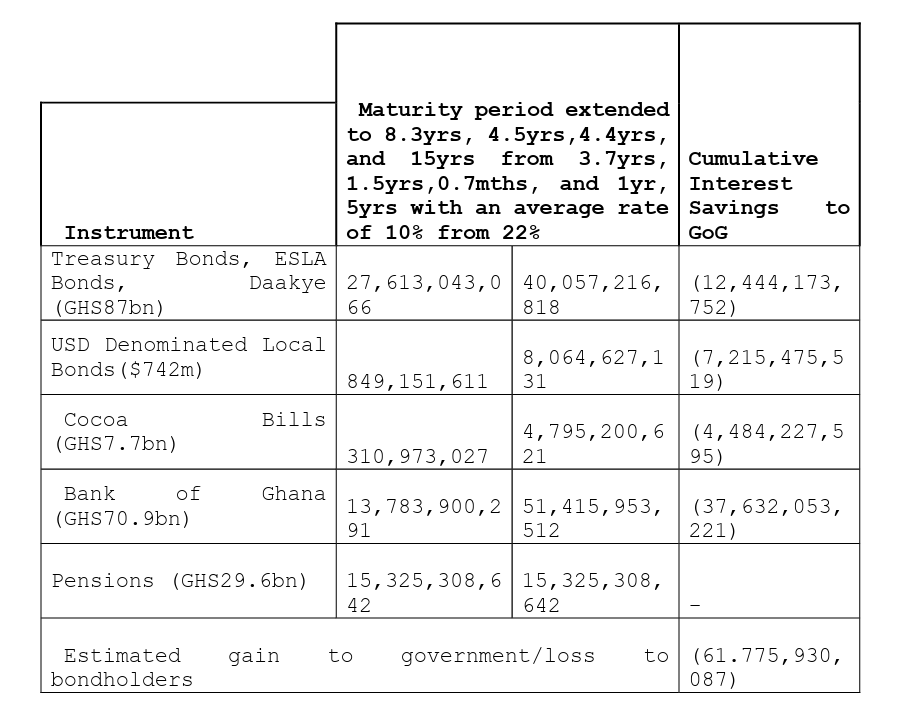

Ghana's economic and financial crisis of the last three years has been the most severe crisis that a developed economy has ever experienced in modern history, both in terms of output and employment loss as well as duration. In 2012, Ghana’s debt increased sharply from GH₵35.1 billion or 48.4% of GDP to GH₵122.6 billion or 73.3% of GDP in 2016, indicating an increase of GHC 87.5 million or 24.9 percentage points of GDP in four years. However, Ghana’s nominal debt has increased from GH₵122.6 billion or 73.3% of GDP to GH₵546 billion or 88.1% of GDP in 2022 and further increased to GH₵610 or 72.5% of GDP despite a comprehensive and painful domestic debt exchange program in September 2023.

The situation in Ghana is a testament to the catastrophic effect that excessive borrowing has exerted on an economy and the disastrous consequences on the social fabric as well as high poverty levels. One of the core issues in this contemporary Ghana tragedy has been public debt. When the crisis started in 2022 with a debt-to-GDP ratio of around 100%, it was interpreted by most economists and policymakers as a public debt crisis. The result of these efforts will be a slowdown of the increase in debt and a boost to growth and therefore a decrease in the debt-to-GDP ratio. Foreign debt accumulated rapidly with corresponding interest payments between 2019- 2022, as the country ran into economic difficulties and suspended payments on foreign debt on December 2022, private and public investment collapsed, with total investment to GDP by as much as 5 percentage points.

Ghana registered the largest fiscal deficits in the past decade, which reached its peak in 2020 with an unprecedented deficit of 15.2% of GDP, thus sharply increasing the country’s debt stock and debt service costs, thereby creating enormous budgetary difficulties, the government of Ghana naturally aimed at achieving fiscal consolidation in the original 2022 budget.

In early 2022, elevated fiscal deficits and public debt levels, together with the combined effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s war in Ukraine, and global monetary policy tightening triggered a drop in international investor confidence in Ghana, resulting in a loss of international market access. This generated increasing pressures on domestic financing, with the government turning to monetary financing by the central bank, which fed into declining international reserves, currency depreciation, and accelerating inflation.

At the beginning of the year 2022, expectations were that the COVID-19 pandemic-induced pent-up demand would be released to boost growth, but the onset of the Russia-Ukraine war introduced new uncertainties, aggravating the existing pandemic-related supply bottlenecks, and challenging the recovery efforts. High inflation, amid tightening global financing conditions, led to a decline in the real incomes of households, a cost-of-living crisis, and weighed on growth.

In response to the heightened inflationary pressures, most central banks raised their monetary policy rates aggressively. The decisive policy actions resulted in the tightening of global financing conditions, with negative spillovers on capital flows to emerging markets and developing economies. (BOG Annual Report 2022). However, by the end of June 2022, Ghana’s economy entered a full-blown macroeconomic and financial crisis on the back of pre-existing imbalances and external shocks.

Large financing needs and tightening financing conditions exacerbated debt sustainability concerns, shutting off Ghana from the international market. Large capital outflows combined with monetary policy tightening in advanced economies put significant pressure on the exchange rate, together with monetary financing of the budget deficit, resulting in high inflation. These developments interrupted the post-COVID-19 recovery of the economy as GDP growth declined from 5.1% in 2021 to 3.1% in 2022 and further declined to 1.7% in 2023. The 2022 fiscal deficit was well above target at 11.8%.

Public debt rose from 79.6% in 2021 to over 88.1% of GDP in 2022, as debt service-to-revenue reached 117.6%. (IMF country report, 2022) According to BOG annual report (2022) opine that on the domestic front, economic growth slowed down to 3.1 percent in 2022 to 1.7% in 2023 from 5.1 percent in 2021, on the back of weakened aggregate demand and supply shocks arising from the lingering effects of the pandemic and geopolitical tensions. Sovereign credit downgrades by rating agencies over fiscal policy implementation and debt sustainability concerns led to a loss of access to the international capital market which, together with low domestic revenue mobilization, negatively impacted the government’s ability to finance the budget. This prompted the Bank of Ghana to intervene to close the widened financing gap to avert domestic debt default and a full-blown economic crisis.

Despite a healthy trade surplus in the previous year, the balance of payments recorded a deficit of US$3.64 billion on account of significant net outflows in the capital and financial accounts. This led to a drawdown of US$3.46 billion in Gross International Reserves from US$9.70 billion at end-December 2021 to US$6.24 billion at end-December 2022, providing 2.7 months of import cover. The significant drawdown in reserves triggered immense currency pressures and the Bank responded in an agile manner with the innovative Gold for Reserves and Gold for Oil programs, as well as a policy to purchase all foreign exchange arising from the voluntary repatriation of export proceeds of mining and oil and gas companies. The country’s stock of domestic debt at the end of December 2022 was GH¢194.39 billion (31.6% of GDP) compared to GH¢181.78 billion (39.5% of GDP) at the end of December 2021.

The increase in the domestic debt stock in 2022 was because of a GH¢11.75 billion increase in short-term securities, and a GH¢629.70 million increase in medium-term securities. Long-term securities, -, increased by GH¢222.50 million. Total public debt stock stood at GH¢545.32 billion inclusive of SOEs and allied debt in end-December 2022 (88.1 % of GDP), higher than the stock of GH¢351.79 billion in end-December 2021. (76.2% of GDP).

The interest payments on the public sector debt increased from GHC 32.53 billion in 2021 to GHC 37.45 billion in 2022 and it remained the single largest item in the 2022 Government annual budget statement. Foreign debt accumulated rapidly with corresponding interest payments between 2019- 2022, as the country ran into economic difficulties and suspended payments on foreign debt on December 2022, private and public investment collapsed, with total investment to GDP by as much as 5 percentage points.

Ghana registered large fiscal deficits in the past decade, which reached its peak in 2020 with an unprecedented deficit of 15.2% of GDP, thus sharply increasing the country’s debt stock and debt service costs, thereby creating enormous budgetary difficulties, the government of Ghana naturally aimed at achieving fiscal consolidation in the original 2022 budget. Heavy public debt service obligations resulted in a large risk premium on interest rates, periodic bouts of financial market instability, and a crowding out of bank credit to the private sector, all of which had contributed to a very low potential growth rate. It is a fact that heavy indebtedness has become the bane of most developing countries in the 21st century, and Ghana is no exception. Consistently, Ghana’s total debt stock has been on a rising trajectory, plunging the country into a debt trap and distress.

The total debt stock at the end of 2022 amounted to GH₵546.15 billion, which constitutes 88.1% of GDP (105% of GDP with the inclusion of key SOEs and allied debts), and it is projected to reach a staggering GH₵863.5 billion at the end of 2023 ( 2023 PwC Ghana Banking Survey Report). The country’s economic fundamentals had deteriorated to the extent that the traditional fiscal consolidation measures embodying expenditure restraint and revenue enhancement measures were inadequate and therefore restructuring had become fundamental to restoring fiscal sustainability.

The Ghanaian economy has witnessed poor revenue growth, and low export earnings from cocoa, gold, and oil because of over-dependence on international capital markets and low tax capacity over the past decade. The country’s debt stock as a result has increased considerably over the past decades – a trend generally connected with expansion in the size of government expenditures. Ghana’s economy entered a full-blown macroeconomic crisis in 2022 on the back of pre-existing imbalances and external shocks.

Large financing needs and tightening financing conditions exacerbated debt sustainability concerns, shutting off Ghana from the international market. Large capital outflows combined with monetary policy tightening in advanced economies put significant pressure on the exchange rate, together with monetary financing of the budget deficit, resulting in high inflation. These developments interrupted the post-COVID-19 recovery of the economy as GDP growth declined from 5.1% in 2021 to 3.1% in 2022 to 1.7% in 2023. World Bank (2022) found that the fiscal deficit widened slightly to 15.2% of GDP in 2020 but further improved to 12.1% of GDP in 2022 due to less spending. Public debt declined from 79.6% in 2021 to over 88.1% of GDP in 2022, as debt service-to-revenue reached 117.6%.

The country’s debt overhang sets in when the face value of debt reaches 60 percent of GDP or 200 percent of exports, or when the present value of debt reaches 40 percent of GDP or 140 percent of exports. The monetization of fiscal deficits and Bank of Ghana lending to government through ways and means advances have risen to GHS 50 billion in 2022, exceeding the threshold set by Bank of Ghana Act 2002 Act 612 as amended Act 2016 Act 918 Section (2) the total loans, advances, purchases of treasury bills shall not at any time exceeds 5% of the total revenue of the previous fiscal year.

These ways and means advances are temporary overdraft facilities provided to the Government of Ghana (GoG) to help with financial difficulties caused by a cash flow mismatch by bridging the gap between expenditure and revenue receipts. This level of borrowing from the Bank of Ghana to finance fiscal deficit was unsustainable, fueled inflation, and endangered growth.

In Ghana, deficit financing has led to borrowings from multinational finance institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the African Development Bank (ADB), and Euro-markets amongst others. Unfortunately, the rising national debt in Ghana began to outweigh the country’s revenue generation capacity and draw down on foreign reserves, hence stifling the much-needed public capital investments and economic productivity. Also, it has been reported that these borrowed funds are often mismanaged and misapplied, hence, were not used for economically productive activities, leading to debt burden, capital flight, and economic instability in the long run. Ghana has accumulated huge debt with the rising cost of debt service which has undermined economic stability as domestic investments are being crowded out by the rising cost of debt servicing.

Komlan and Essosinam (2022) opined that nations that adopt unsustainable fiscal policies have an ever-increasing debt-to-GDP ratio that violates their budgetary restraint. High debt levels resulted in high debt servicing, which has led to a low amount of money available for investment in infrastructure and other economic sectors. Ghana’s debt profile continued to increase in the face of expanding fiscal deficit and low revenue-generating capacity.

This was concerning because the country’s debt profile became more and more dominated by commercial debt. Weak fiscal and economic performance over extended periods led to an unsustainable fiscal situation for Ghana in 2022 which led to the domestic debt restructuring. One of the core issues in this contemporary Ghana trajectory has been rising public debt over four years. When the crisis officially started in 2022 with a debt-to-GDP ratio around 88.1%, it was interpreted by most economists and policymakers as a public debt crisis.

As a result, the austerity measures of the last three years including higher taxes have been imposed to address this problem. Fiscal consolidation, together with structural reforms, is supposed to generate large fiscal surpluses, reinvigorate investment, and enhance the competitiveness of the economy and thus net exports. The result of these efforts will be a slowdown of the increase in debt and a boost to growth and therefore a decrease in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Austerity and structural reforms are thus imposed to a large extent in the name of the sustainability of debt. The goal of the present paper is to provide a comprehensive and well-rounded examination of the issue of Ghana's public debt and its role in the crisis. We start with a historical discussion of the accumulation of Ghana's public debt before 2016 and the reasons that led to the increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio over time.

A historical account of the Ghana public debt serves as a basis for the discussion of the role of the debt during the crisis. We make three main points. First, the imposition of austerity and “structural reforms” in the name of debt sustainability has pushed the economy into a debt-deflation trap: austerity leads to a fall in the GDP and thus an increase – ceteris paribus – of the fiscal deficit. These two effects lead to an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio and make more austerity and more “structural reforms” necessary.

The swirling of the Ghana economy in this vicious cycle has grave social and political consequences. This discussion of the experience of the last three years shows that Ghana’s public debt is unsustainable; therefore, we argue that a bold restructuring of the debt is needed for the Ghana economy to reignite its engine of growth. Ghana’s debt sustainability will depend upon four ingredients- primary balances; real growth devoid of higher inflation; real interest rates as well as reasonable debt levels. Higher primary balances excess of government revenue and expenditure excluding interest payments and growth help to achieve debt sustainability, but unfortunately, higher interest payments and higher debt levels are making debt sustainability more challenging. An insistence on the current policies is not justifiable on pragmatic, moral, or any other grounds.

Theoretical Underpinning: Debt Sustainability and Fiscal Stability.

Osei (2000) argued that there is no gainsaying that sustained economic growth is possible only within a sound macroeconomic framework. In such a framework, fiscal policy plays a key role; sound fiscal policy is crucial to macroeconomic stability. Essentially, there is a link between public debt sustainability and fiscal stability, especially in a situation like Ghana's, where both external and domestic debt are evenly distributed as public sector debt. The theoretical underpinning of the link between both external and domestic debt and fiscal behavior is quite straightforward.

There are four ways of financing a public sector deficit: printing money, running down foreign exchange reserves, borrowing abroad, and borrowing domestically. Each of these forms of finance resulted in major macroeconomic imbalances and economic crisis in 2022: the Bank of Ghana had to fall back on its buffers and policy space to provide the needed additional support through the purchase of GH₵10 billion of the Government’s Covid-19 bonds, which helped to close the exceptional financing gap but led to higher inflation in 2023; the lack of access to the market for new financing immediately triggered a liquidity crisis, spilling over into a balance of payments crisis as the country had to continue to honor debt service obligations and energy payments using of foreign reserves that led to the exchange crises; excessive foreign borrowing led to external debt crises in 2022 and the excessive domestic borrowing from the local bond and money markets led to higher real interest rates which propelled crowding out of the private sector. Of course, there were links between and among these problems.

For example, high transfers because of a debt crisis caused government domestic borrowing to increase. This increase reduced credit that otherwise would be available to the private sector, thereby putting pressure on domestic interest rates.

Even where interest rates are controlled, domestic borrowing led to credit rationing and crowding out of private sector investment. The straw that broke back the economy in 2022 was a result of sovereign spreads on Ghana bonds widening, and credit rating agencies further downgraded Ghana’s sovereign debt rating, which effectively blocked Ghana’s access to the international capital markets (Addison, 2023). The arithmetic of the relationship between public debt and fiscal behavior is as follows. The increase in the sum of domestic and external debt is equal to the government budget deficit, net of money creation. If only the government borrowed abroad, then the decrease in the government's external debt would be equal to the current account balance. Therefore, the current account balance is the sum of the increase in domestic government debt, the budget surplus, and money creation (IMF 2000).

Historical Perspective of Ghana’s Public Debt Crisis

Before discussing the role of Ghana's sovereign debt during the current crisis, it is worth making a short historical discussion of its path over the past ten years. Besides its historical interest, this discussion is necessary to understand the crisis and the future challenges of the Ghana economy. A more detailed exposition was provided in Atuahene (2022). The theoretical discussion of the link between public debt and fiscal behavior was quite straightforward. There were four ways of financing a public sector deficit: printing money, running down foreign exchange reserves, borrowing abroad, and borrowing domestically. Each of these forms of finance resulted in a major macroeconomic imbalance in 2022. In addition, the Bank of Ghana had to fall back on its buffers and policy space to provide the needed additional support through the purchase of GH₵10 billion of the Government’s Covid-19 bonds, which helped to close the exceptional financing gap led to higher inflation in 2022; the drawdown of foreign reserves in settlement of interest and principal on Eurobond holders led to exchange crises; excessive foreign borrowing led to external debt crises in 2022; and over domestic borrowing led higher real interest rates that propelled the crowding out of the private sector.

In addition to, four ways that contributed to the current public debt crisis, sovereign spreads on Ghana bonds widened, and credit rating agencies further downgraded Ghana’s sovereign debt rating, which effectively blocked Ghana’s access to the international capital markets in 2022. According to Ministry of Finance data Ghana’s total public debt in 2012 stood at GHC 35.9 billion (US$19.2 billion) thus represented 47.8% of GDP after rebasing in 2010 but increased significantly to GHC 53.1 billion (US$24.4 billion) or 56.8% of GDP in 2013.

In 2014, Ghana’s public debt rose to GH₵79.5 billion (US$ 24.7 billion) or 70.2% of GDP and further increased significantly to GHC 100.2 billion (US$ 26.4 billion) in 2015 thus representing 72.2% of GDP. By the end of December 2016, the public debt stock stood at GHC 122.2 billion (US$ 29.3 billion) thus representing a debt/ GDP ratio of 72.5%. Ghana’s public debt stock stood at GH₵146.6 billion (US$ 32.3 billion) at the end of 2017, up from the 2016 figure of GH₵122.3 billion (US$ 29.3 billion).

The total public debt as a percentage of GDP declined from 73.2% in 2016 to 69.8 % of GDP in 2017. Ghana’s public debt stock as of the end of December 2018 was GH₵173.1 billion (US$ 35.9 billion) representing 57.9% of the rebased GDP. According to the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning Annual Debt Review (03/2019), a large part of the 2018 public debt stock additions of GHC 11.1 billion resulted from the banking sector bail-out program of the government. The cost incurred by the government to clean up the banking sector impairments resulted in the public debt increasing by 3.2% of the rebased GDP. Excluding the bail-out costs, however, the stock of public debt amounted to GH₵163.4 billion (US$ 33.9 billion) thus representing 57.9% of rebased GDP as of the end of December 2018. At the end of December 2018, the stock of external debt was GH₵86.2 billion (US$17.9 billion) representing 28.9% of GDP while the domestic debt stood at GHC 86.78 billion which represented 28.9% of GDP. By the end of June 2019, the stock of public debt rose to 59.2% of GDP (GHC 204 billion compared with December 2018 representing 57.9% of rebased GDP.

Thereafter, domestic debt increased very sharply, reaching GH₵86.2 billion in 2018 and then to GH₵94.8 billion at the end of May 2019. This indicates that domestic debt increased by GH₵4.1 billion between 2000 and 2008, GH₵13.6 billion between 2008 and the end of 2018 later increased to GHC 94.8 billion at the end of May 2019. Total domestic debt stood at GH₵86.889.3 billion at the end of December 2018, indicating an increase of GH₵6.0 billion by the end of March 2019. Ghana’s debt stock as of the end of December,2018 stood at GH₵173,068.7 billion (US$ 35,858 billion) comprising external and domestic debt of GHC 86,169 billion (US$ 17.868 billion) and GH₵86.9 billion (US$18.020 billion) respectively.

This represented 57.9% of the debt/GDP ratio. External and domestic debt accounted for approximately 49.7% and 50.3% respectively. The Cedi recorded a cumulative depreciation of 8.4% against US$ as of the end of December 2018 and this impacted negatively on external debt. The total public debt stock has increased from GH₵173 billion at the end of December 2018 to GH₵198 billion at the end of March 2019 further increased to GH₵204 billion at the end of June 2019.

The external debt stock increased from GH₵86.2 billion in December 2018 to GH₵115 billion at the end of June 2019. Similarly, the domestic debt component has also increased from GH₵86.9 billion at the end of December 2018 to GH₵99.8 billion at the end of March 2019 but declined to GH₵94.6 billion. Ghana’s total public debt rose to 54.8% of the GDP (GH₵198.0 billion) at the end of March 2019 compared with 57.9% of the GDP at the end of December 2018 but increased further to GH₵204 billion or 59.2% of GDP in June 2019.

Of the total public debt stock of GH₵198 billion, GH₵11.0 billion or (3.2% of GDP) represented bonds issued to support the banking sector cleanup. As a percentage of the GDP, the external debt has declined marginally from 29.6% in 2018 to 26.3 % at the end of March 2019, while domestic debt increased from 29.3% in December 2018 to 31.2% at the end of March 2019. The stock of public debt rose to 59.2% of GDP (GH₵204 billion) at the end of June 2019. Of the total debt stock, domestic debt was GH₵94.6 billion (27.5% of GDP) while external debt was GH₵105. 4 billion (30.6 % of GDP) and the end of June 2019. The accumulation of public debt has been a direct result of the gap between unplanned expenditures and revenues, which has widened due to the inelasticity of debt servicing and infrastructural needs, deteriorating terms of trade, and the failure to improve and enhance revenue collection over the long period. Ghana’s public debt stock stood at GH₵173.1 billion (US$35.9 billion) at the end of December 2018.