1. Brief background

By the end of the 3rd Quarter of 2021, Ghana’s fiscal vulnerability had been evident to the market resulting in a loss of market access largely consistent with the country’s struggle to manage its public debt since independence. In all of Ghana's program engagements with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), debt unsustainability has been recurring reflecting a weak fiscal regime of expenditure rigidities and low domestic revenue mobilization.

The latest IMF Supported Program is unique given the number of prior actions the country had to undertake in order to qualify for help from the IMF including taking a comprehensive approach to restructuring the country’s public debt with the domestic debt restructuring being a condition precedent to getting IMF Board approval. Unlike the case of Zambia, which excluded the domestic debt from its debt restructuring to protect the domestic financial system, Ghana applied the most aggressive debt restructuring which was first announced on December 5th, 2022.

Arguably the first of its kind in the history of the country. Government instruments (excluding only treasury bills) held across households (including pensioners), financial institutions, body corporate, and resident and non-resident investors were considered to be in the universe of eligible bonds. The country’s economic fundamentals had deteriorated to the extent that the traditional fiscal consolidation measures embodying expenditure restraint and revenue enhancement measures were considered to be inadequate and therefore restructuring had become fundamental to restoring fiscal sustainability.

2. Overview of the original DDEP impact on the banking sector

The Ministry of Finance invited on 5th December 2022 holders of 60 old domestic debts to voluntarily exchange GHC 137.3 (US$14.3) billion domestic bonds and notes including E.S.L.A and Daakye Bonds, for a package of twelve new eligible domestic bonds. Under the debt swap or exchange announced on 5th December 2022, local holders including domestic banks, Bank of Ghana, Firms and Institutions, Retail and Individuals, insurance companies, foreign investors, Rural and Community Banks and SSNIT were to exchange GHC 137.3 billion (US$14.3) worth of 60 eligible domestic bonds for twelve new eligible bonds maturing between 2027 to 2038.

Under the initial offer, for bondholders with bonds maturing in 2023, the government promised four new bonds that were expected to mature in 2027, 2029, 2032 and 2037 with zero (0) coupon rate in 2023, 5% coupon rate in 2024 and 10% coupon rate in 2025, which would continue till the maturity of last bonds in 2037.

Initially, the Ministry of Finance stated that debt exchange program would affect local banks, Bank of Ghana, firms and institutions, foreign investors, insurance companies, pension funds, rural and community banks and SSNIT but excluding retail and individual bondholders. The debt exchange program was extended to 30th December, 2022 because could not achieve the 100% voluntary participation.

After fierce resistance from Trade Unions about the inclusion of pension funds in the domestic debt exchange program and for the lack of enough voluntary participation, the government announced the extension of the voluntary participation in the program to 16th January 2023 with following modifications: Offering accrued and unpaid interest on eligible bonds and a cash tender fee payment to holders of eligible bonds maturing in 2023 (ii) increasing the new bonds offered by adding new instruments to the composition of the new bonds for a total of 12 new domestic bonds, one maturing each year starting January 2027 and ending January 2038. (iii) Modifying the exchange consideration ratios for each new bond. The exchange consideration ratio applicable to Eligible bonds maturing in 2023 will be different other from other eligible bonds; (vi) Setting a non-binding target minimum level of overall participation of 80% of the aggregate principal amount outstanding of eligible bonds and (vii) expanding the types of investors that can participate in the exchange to include individual investor.

On January 16th 2023, the government extended deadline of domestic debt exchange program to 31st January,2023 after another resistance by some creditor group particularly individual investors whom the government promised not to include in the program. The government made some modifications including (i) offering accrued and unpaid interest on eligible bonds and a cash tender fee payment as a carrot to holders of eligible bonds maturing in 2023. (ii) increasing the new bonds offered by adding eight new bonds to the composition of the new bonds, for a total of 12 new bonds, one maturing each year starting in January, 2027 and ending January 2038.

The third extension of deadline for domestic debt exchange program from 31st January 2023 to 7th February,2023 for voluntary participation and also as the final deadline for institutions and individuals to sign up to domestic debt exchange program. The government has made offer which includes the exchange of new bonds with a maximum maturity of 3.8 years instead of original 13.8 years and a 10% coupon rate to individual bondholders below the age of 59 years to encourage them to participate in the domestic debt exchange program.

Additionally, all retirees including those retiring in 2023 will be offered bonds with a maximum maturity of (3.8 years) 5yrs instead of 13.8 years (15yrs) and a 19.1% coupon rate per annum to 9.1% per annum Subsequent extensions of dates and payment maturities meant that the remaining stock was reduced from GHC137.3 billion to GHC130 billion. However, the eligible bonds as per memorandum meant an exclusion of pension funds and bonds that were subject to swap mechanisms for monetary and exchange rate policy operations. This then brought the eligible bonds tendering to GHC 97.75 billion.

Out of the total eligible bonds for tendering, GHC 83 billion (US$ 6.7 billion) was successfully tendered-accounting for about 85% of outstanding eligible amounts and meeting the target 80% as expressed in the memorandum of the exchange. Nevertheless, the GHS 87.8 billion (64%) that were successfully tendered represent only 60% of the original outstanding debt stock of GHS137.3 billion. Ghana exchanged C87.8 Billion out of the total domestic debt of GHS 193.1 billion that average coupon rate of 19.1% with bond returning as little as 9.1% with extended period from 3.8 years to 13.8 years.

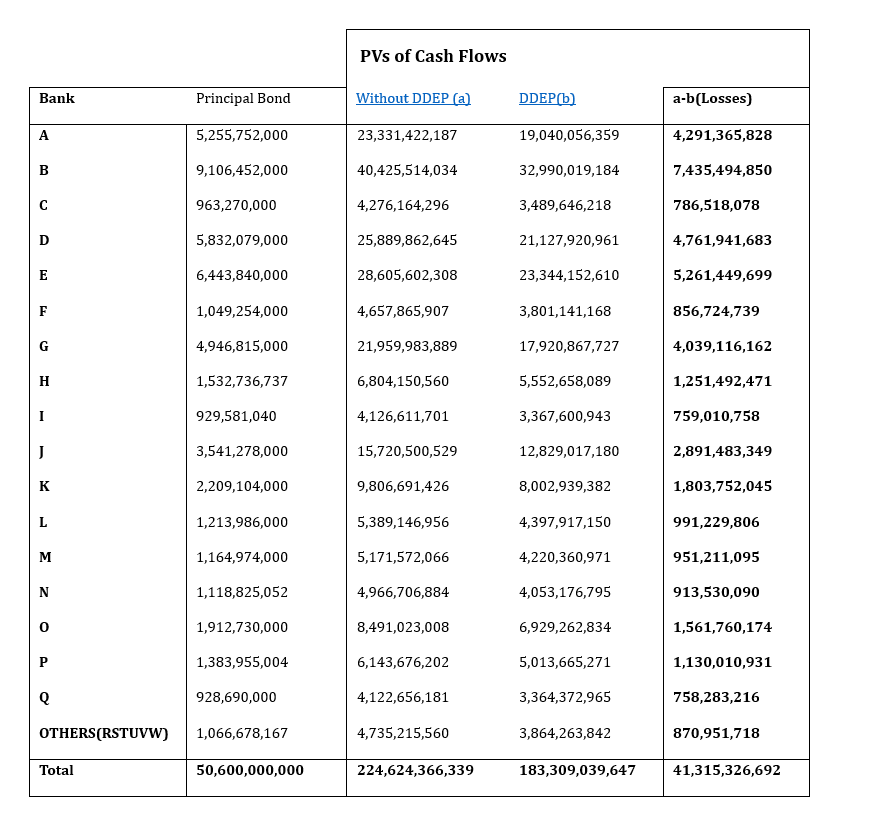

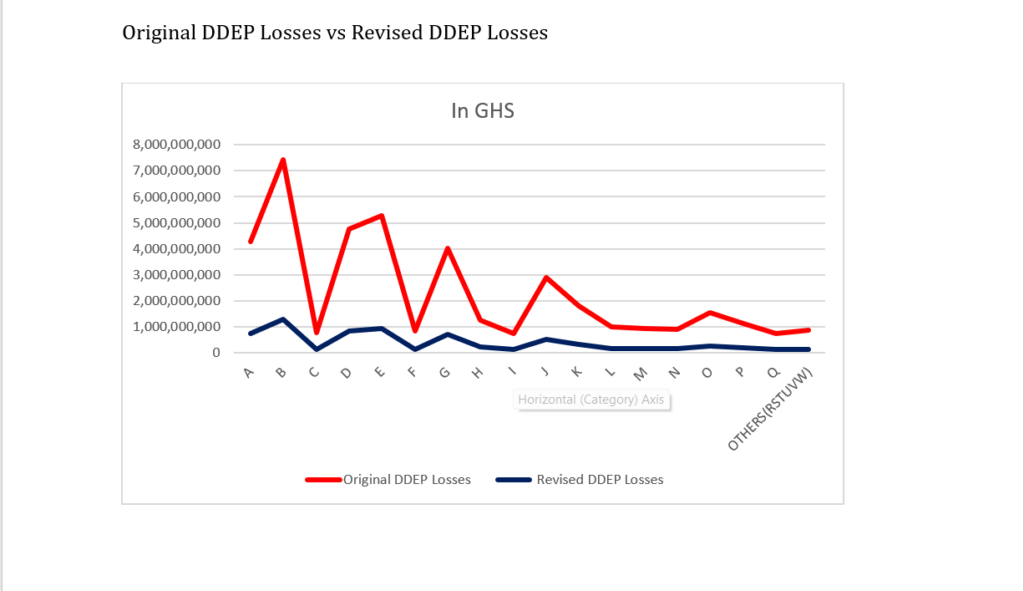

Using the 16% discount rate for the NPV for government bonds valued GHS 50.6 billion resulted in DDEP losses of 22 banks capturing at GHS 37.7 billion in 2022 with the private domestic banks and state-owned banks accounted for losses of GHC 19.9 billion while foreign owned banks accounted for (GHS 17.8 billion while leaving uncaptured losses of (GHS3.7). The DDEP impairment losses have technically rendered some of Ghanaian local owned banks insolvent that would require additional capital support from shareholders or participate fully in the Ghana Financial Stability Fund.

According to IMF Country report (23/168), the World Bank, other donors and the government of Ghana were expected to provide GFSF to amount of US$1.5 equivalent in Cedis to facilitate the build- up of capital buffers for qualifying banks. The local or indigenous banks have already submitted their credible time bound plans to rebuild capital buffers on a phased basis in line with timelines set in the country’s financial sector strategy.

These recapitalize plans would have to be reviewed by Bank of Ghana and finalized by banks for approval by Bank of Ghana by the end of September, 2023. For capital restoration for local banks, the preference or priority must be given to those local banks that are not quoted and listed on the Ghana Stock Exchange Market as those listed banks are expected to raise additional capital on market.

The capital restoration of the local/indigenous banks must take it in consideration of the entire losses for their participation in the DDEP and the deletion of all the regulatory reserves in the balance sheets of those banks. There has been heightened need for the recapitalization of banks operating in Ghana after the domestic debt exchange program in December, 2022, and it has been spearheaded by the foreign owned banks operating in the country.

A couple of months ago, Standard Bank.SA (Standard Bank), and First Rand SA-both based in South Africa revealed their plans to recapitalize their operations in Ghana even before the submission to recapitalization plans to Bank of Ghana. Standard Bank (Stanbic) has reportedly reserved South Africa Rand (ZAR) 1.5 billion approximately US$ 81 million for impairment losses from the DDEP. Also, Nigerian owned bank Zenith has revealed that it has set aside US$ 265 million to ring fence its impairment losses as a result of the participation of DDEP.

Domestic bonds were widely distributed across the financial sector in Ghana, representing the most important asset class held by 22 universal banks, specialized deposit taking institutions, pension funds, asset management companies, and insurance companies. Banks held 30 to 50 percent of their total assets in government securities before the DDE—with especially high exposures in the state-owned banks—and relied significantly on income from these securities.

The coupon reductions and maturity extensions in the recently completed DDEP mean that the value of these assets had declined to about 70 percent of the par value. (IMF Country report, 23/168). From IMF report (2021) domestic debt restructuring have a direct impact on the balance sheet and earning potential of financial institutions holding sovereign debt.

The impact on bank balance sheets could be significant where sovereign securities comprise a large share of bank asset as Ghanaian banks held about 30% to 50% of the government bonds. Any loss in value of government debt exposures have led to serious capital losses in banking institutions as most banks never absorbed by provisioning and mark-to-market (MTM) accounting.

These losses were due to a combination of coupon or interest rate reduction, and maturity extension with below-market coupon rates of 19.1% as a result of the domestic debt exchange implementation. According to IMF country report (23/168) the government offered most bondholders a set of new bonds at fixed exchange proportions with a combined average maturity of 13. 8 years and coupons of up to 10 percent (with part of the coupons capitalized rather than paid in cash in 2023 and 2024). The capacity of the banking sector to absorb losses were lower as some of the banks were not properly capitalized. When banks are able to absorb losses without having to resort to a recapitalization from the government, the fiscal consolidation and/or burden-sharing by other creditors required to restore debt sustainability would be smaller.

According to IMF country report (23/168), the completed DDEP has produced very large cash debt relief for the government of almost of GHC 50 billion in 2023 and the baseline fiscal cost of DDEP to the financial sector is up to 2.6% of GDP. The recent domestic debt exchange program of unprecedented size and dire consequences is a major concern throughout today’s society, from the popular press to policy-makers, regulators and academics around country.

The near collapse of prestigious local banking institutions could be followed by the near paralysis of the banking sector with negative consequences for the real economy, makes the past crisis a singular point in the series of modern crises and unquestionably qualifies it as the most severe one since independence of the country’s in 1957.

The uniqueness of the crisis has prompted efforts to identify its determinants and the solutions to cope with it. The crisis is frequently attributed to the bursting of the Ghana’s bond market bubble bust but such a complex event presents a multidimensional profile as well as poor and lax risk management and regulatory capture and failure on the part of the banking fraternity.

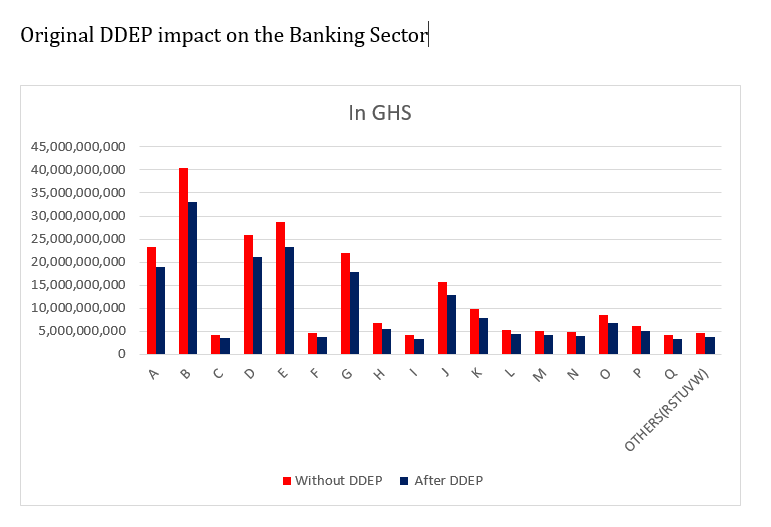

Original DDEP impact on the Banking Sector

Original DDEP impact on the Banking Sector

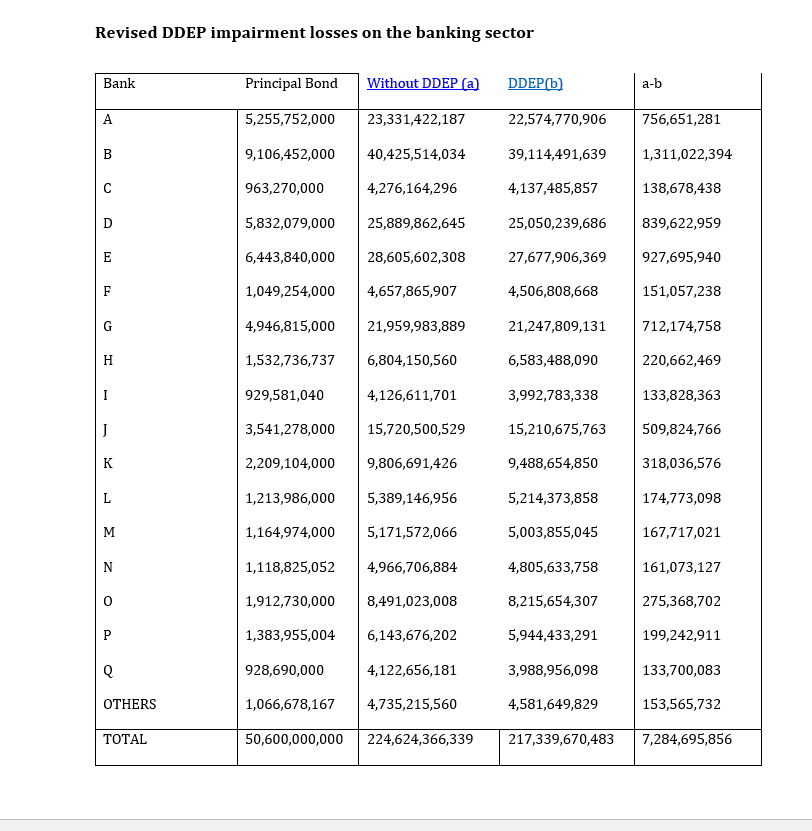

3.0. The Overview of Revised DDEP impact on the Banking sector

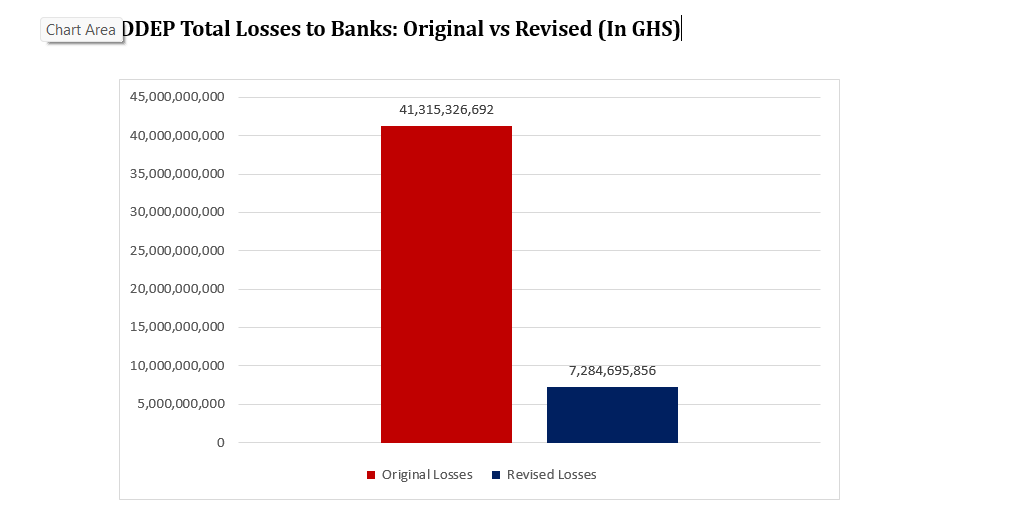

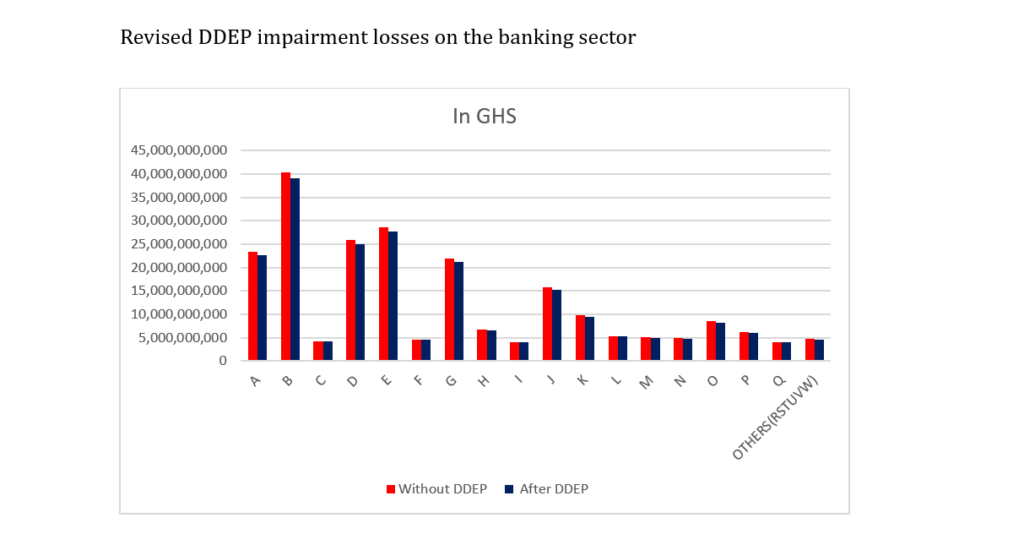

The 22 universal banks, auditors of the individual banks, Bank of Ghana and the Ministry of Finance agreed at a 16%-18% discount rate as the final terms of the DDEP implying an average NPV reduction of about 14% for government bond holders (IMF Country report, 23/168). Using the 16% discount rate for the NPV for government bonds calculation resulted in DDEP losses of 22 banks stood at GHC 7.3 billion with the foreign banks, private domestic banks and state-owned banks accounting for losses. The Banking sector held about GHC 50.6 billion out of GHS 87bn restructured from Treasury bonds, ESLA and Daakye bonds excluding pension funds.

The average coupon rate and maturity period of the restructured bonds currently stands at 9.1% (previously 19.1%) and 8.3 years (previously 13.8 years). Using the 16% discount rate for the NPV for government bonds calculation resulted in DDEP losses of 22 banks stood at GHS7.3 billion. The revised DDEP overall losses of GHC7.3 billion with foreign owned banks losses stood at GHS2,995,387,32 while state owned banks at GHS2,377,396,772 with privately domestic bank at GHS1,911,911,762. These revised DDEP had impacted marginally on both banks’ solvency and liquidity but significantly and negatively impacted on the non-performing assets has increased from 15% in 2022 to 20% in 2023.

The DDEP impairment losses of GHS 7.3 billion as an impairment due to the introduction of expected loss provisioning under the IFRS 9 accounting standard. The banking sector of Ghana has suffered marginal losses in the revised domestic debt exchange program had moderate impact on solvency and liquidity of the banks.

The twenty- two Ghanaian banks reported the combined write-back on Government of Ghana bonds in their balance sheets following the sovereign debt restructuring amounted to GHS7.3 billion. The NPV losses in 2022 was 30% as against 14% losses in the revised DDEP in 2023 as a result of the reduction of maturity period from 13.8 years to 8.3 years.

4.0. Discussion of findings in the revised DDEP implications on the Banking Sector

The revised DDEP had a marginal impact on the balance sheet and earning potential of financial institutions holding government debt. The impact on bank balance sheets was moderately significant because the twenty-two banks held more 50% of sovereign securities comprise a large share of bank assets. With the reduction from 13.8 years to 8.3 years and the reduced coupon rate of 19.1% per annum to 9.1% per annum the loss in value of government debt exposures led to marginal capital losses in banking institutions unless these have already been absorbed by provisioning and mark-to-market (MTM) accounting. These marginal losses were due to a combination of coupon or interest rate reduction from 19.1% per annum to 9.1% per annum, and maturity reduction from 13.8 years to 8.3 years with below-market coupon rates of 19.1%.

The capacity of some the banking institutions had a bigger capacity to absorb losses as they were well capitalized. While some of the state owned banks were not able to absorb losses without having to resort to a recapitalization from the government financial stability fund. Capital shortfalls were more likely to emerge for a tail of weak banks like some state owned banks and for those banks had a high share of exposure to government domestic debt relative to their capital. With the revised DDEP, most of the banks would have write back of losses in 2022 that could make some banks more profitable and capital compliant with regulatory capital adequacy ratio in 2023.

From the comparative analysis on both the original DDEP and Revised DDEP impact on the banking sector showed that NPV losses have reduced from GHS 41.3 billion to GHS7.3 billion respectively. From data analysis most banks including will have huge write back for the losses incurred in 2022 to improve on capital adequacy ratios. These revised DDEP had impacted marginally on both banks’ solvency and liquidity due to a combination of coupon or interest rate reduction from 19.1% per annum to 9.1% per annum, and maturity reduction from 13.8 years to 8.3 years. With the revised DDEP, most of the banks would have write back of losses in 2022 that could make some banks more profitable and capital compliant with regulatory capital adequacy ratio in 2023.

First, the domestic debt exchange has negatively affected availability of credit and cost of borrowing from some banks for corporations and households, with potential indirect distributional effects. This has called for a thorough assessment and mitigation of the distributional implications of the restructuring on case-by-case basis.

The consequences of domestic debt exchange if not properly managed could render banks unable to support private businesses which could have negative impact economic growth with small and medium sized enterprises being the worst culprit. This has the tendency of hindering economic growth of the private sector which is said to be engine growth thereby negatively impacting job creation which is needed in the economic recovery process. This represented the first study that explicitly accounted for the size of the haircut when determining the historical consequences of default.

The main conclusions were that deeper haircuts are associated with higher post‐restructuring global bond spreads and longer duration of exclusion from capital markets. Further, if there were a debt restructuring the perception of increased risk of government debt was expected to significantly blunt confidence in the Ghanaian economy in general, thereby affecting the creditworthiness of private institutions as well.

This has translated into a further cut in credit lines to some of domestic banking institutions especially the state owned banks, which would have grave implications for external trade and the stability of the foreign exchange market. Ghanaian domestic banks had already suffered the effects of cuts in credit lines and margin calls by corresponding banks as a result of the international credit crunch in the post Covid19 period. Further withdrawal of credit lines and margin calls have had devastated effects on the international trade system, financial markets and in the Ghanaian economy in general. As most corresponding banks have withdrawn their credit lines especially with the local banks

Second, another negative effect of domestic debt exchange is that it has caused investors to lose confidence in the country's ability to repay its debt on time. The DDEP has had a significant impact on investor confidence in the fixed-income market in Ghana. The sudden loss of value for existing bondholders has led to concerns about the safety of government-issued securities and has shaken investor confidence. Investors who previously considered government-issued securities as risk-free investments are now be more cautious and may require a more thorough assessment of risks before investing in fixed-income securities.

The decline in investor confidence also had broader implications for the fixed-income market in Ghana. Reduced demand for government-issued securities have led to higher borrowing costs for the government in the money market, as government had needed to offer higher coupon rates to attract domestic investors. This had increased the cost of debt servicing for the government and impact the country's overall fiscal management.

Additionally, lower investor confidence may also result in reduced liquidity in the fixed-income market, as investors may be hesitant to buy or sell securities, further affecting market dynamics. This has led to a decrease in foreign investment and an increase in the cost of borrowing for the government and local businesses with yearly treasury bill rates had surging from 22% in 2022 to 33.7% post DDEP era.

Third, the higher interest rates on treasury bills has also affected the country’s banking institutions thus creating an adverse selection problem. As interest rates rise more conservative, risk-averse borrowers shy away from the credit market. A larger proportion of the persons applying for loans are thus those who are willing to take risky bets. The likelihood of default increases and so therefore does the banks’ proportion of non- performing loans.

The recent Bank of Ghana’s report on the increases in the non-performing asset ratio from 15% to 20% confirmed the debt crowding hypothesis. Weaker economic activity has translated into higher non‐performing loans by both firms and households which could increase bank distress through balance sheet and liquidity effects. The recent currency depreciation has also exacerbated non‐performing loan volumes through currency mismatches.

Fourth, domestic bond restructuring episode has marginally impacted on the financial sector of the country for several reasons. First, the asset side of banks’ balance sheets took a direct hit from the loss of value of the restructured assets, such as government bonds. Second, however, on the liability side, Ghanaian banks did not experience deposit withdrawals and the interruption of interbank credit lines. These issues marginally affected their ability to mobilize resources at a time of stress. Finally, restructuring episode has also triggered interest rate hikes, thereby increasing the cost of banks’ funding and thus affected their non-performing assets. Together, these factors marginally impaired the financial position of some domestic banking institutions to such a degree that financial stability was threatened and pressures for bank recapitalization and official sector bailouts are increased.

Lastly, the domestic debt exchange program had moderately affected the foreign banks from Nigeria, South Africa, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago, United Kingdom, Morocco, and France and all that financial institutions that are operating in the country that have been exposed moderately to country risks in Ghana that underwent domestic debt restructuring which transmitted the shock across borders, be it directly via loss of value of government securities or indirectly via their exposure to the Ghanaian banking sector which have resulted in marginal DDEP losses for which most them have started recapitalization process.

The direct costs of revised domestic debt exchange in Ghana do not pose a serious threat to the success of sovereign debt restructuring as they will be covered by the bailout funding under Ghana Financial Stability Fund. Safeguarding financial stability included liquidity and solvency support to banking institutions affected by the domestic debt restructuring, as well as temporary capital flow management measures and the Ministry of Finance and Bank of Ghana interventions to support orderly market functioning.

5.0. CONCLUSION

The implications of a domestic debt restructuring were not limited to a one-time value tax on domestic debt holdings or, in other words, a one-time NPV loss to the debt holders, however. Where the government domestic debt is a structural necessity i.e., in case of universal banks including the central bank, insurance companies, and other regulated financial institutions, these entities have faced mild equity erosion requiring fresh capital injections, liquidity crunches, and maintenance of minimum capital challenges, however in the case of revised domestic debt exchange implemented the banking sector was hit marginally after the reduction of maturity period from 2038 (13.8 years) to 2031(8.3 years) and reduction in the coupon rate from 19.1%per annum to 9.1% per annum. The restructuring of domestic debt was an inevitable step, given the insolvency of the country with no access to the markets and alarming prospects of debt evolution in the future.

Reducing the burden of domestic debt by GHS 61.7 billion (Ministry of Finance 2023) is likely to give Ghana some breathing space, while the bailout loans by the IMF and the World Bank will provide Ghana with the necessary time to get back on its feet. The domestic debt restructuring itself will not solve the root cause of the problems though – an inability to sustain primary balance, deeply rooted lack of competitiveness, deep seated corruption of Ghana and inefficiencies and regulatory capture of a regulatory and supervisory authorities, improve domestic revenue mobilization, reduction in the government expenditure and non-existent debt cap or debt limit in the constitution are the recipe for future domestic debt restructuring.

6.0. Implications for future domestic debt restructuring.

Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring fell below the global standards for stable capital flows and fair debt restructuring for emerging market for the lack of transparency, poorly and timely flow of information, bad faith of actions, unfair treatment of some creditors and not communicating the debt exchange as financial transaction.

- Importantly, the debt exchange was not communicated simply as financial transactions but rather as an integral underpinning to Ghana's strategic economic program which included significant fiscal reforms buttressed by the planned elimination of the fiscal deficit in the near term.

- Lack of transparency and poor timely flow of information regarding the changes in the coupon rate from 19.1% to 9.1% and drastic changes in reduction in maturity period from 13.8 years to 8.3 years for Treasury bonds, Daakye and Esla Bonds. For debt restructuring to achieve its target requires transparency of exchange Process. The intensive dialogue with creditors and the provision of extensive economic and financial information contributed significantly to the success of the exchange program.

- Bad faith action was initially demonstrated by the Government through exemption of the retail and individuals from original domestic debt exchange program in December, 2022 but with the inclusion pension funds but reversed the decision. There wasn’t extensive but informal consultation prior to the launch of both exchanges with a small group of large bondholder institutional investors. However, good faith principles encourage the Ghana government to engage in actions designed to establish conditions for renewed market access on a timely basis, viable macroeconomic growth, and balance of payments sustainability over the medium term.

- The government did not treatment of creditors fairly as the government varied the terms of domestic debt exchange program three times since December, 2022. A major consideration in the debt exchange process was according fair treatment to all classes of domestic creditors as the government originally exempted the retail and individuals from the original program on 5th December 2022. No creditor, creditor group or instrument should be excluded ex ante from participating in debt restructuring and decisions need to be made on a case-by-case basis in close coordination with relevant stakeholders. Broad creditor participation in debt restructuring operations is essential to ensure fair burden sharing, and to assess the impact of the provision of new financial assistance, as well as the appropriate ranking of creditor claims. Fair treatment of all creditors is in the interest of both sovereign debtors and creditors. It lessens the burden on all creditors and, by ensuring a fair burden sharing, encourages creditors to participate voluntarily in debt resolution and minimizes any adverse impact on the investor demand for existing or new issues of sovereign debt by the sovereign debtor undergoing debt restructuring or by others in the asset class.

For Future domestic debt restructuring the Government must that the following issues are properly and adequately addressed: lack of transparency, poorly and timely flow of information, bad faith of actions, unfair treatment of some creditors and not communicating the debt exchange as financial transaction.

END-

By Dr. Richmond Atuahene, K. B. Frimpong (FCCA.UK) & Isaac Kofi Agyei

Latest Stories

-

11 inmates of Manhyia Local Prison trained in batik, tie and dye craftsmanship

9 minutes -

President of Rugby Africa Herbert Mensah arrives in Uganda ahead of the RAC2025

10 minutes -

Inlaks wins Banking Technology Provider of the Year; Yacoba Amuah wins Outstanding Woman in Tech at DIA Awards

21 minutes -

GTA launches 2024 Ghana Tourism Report in Accra

25 minutes -

NSMQ 2025: Nyakrom SHTS crushes competition in silent but dominant NSMQ performance

44 minutes -

ECG assures KATH of stable power supply

2 hours -

We don’t need to create an authority for 24H Economy – Prof Bokpin

2 hours -

Joseph Paintsil scores twice in LA Galaxy win over Vancouver

3 hours -

NSMQ 2025: Mankessim SHTS pulls off shocking final-round win over Assin State College in Central Regional qualifiers

3 hours -

EC fears NDC over Ablekuma North electoral dispute – Kofi Bentil

4 hours -

‘Whether you boil it or fry it, the NDC will remove you’ – Kofi Bentil to EC commissioners

4 hours -

Memphis University threatens to drop Ghanaian scholarship students over unpaid fees by gov’t

4 hours -

Asutifi North public sector workers petition authorities over soaring cost of living

4 hours -

Let us rise above partisan politics to develop our district – DCE

4 hours -

Ablekuma North: All three chairpersons of the EC should resign – Kofi Bentil

4 hours