In Japan, as parts of the country declare a state of emergency, people here have been reacting to the Covid-19 pandemic in a unique way: by sharing images online of a mystical, mermaid-like being believed to ward off plagues.

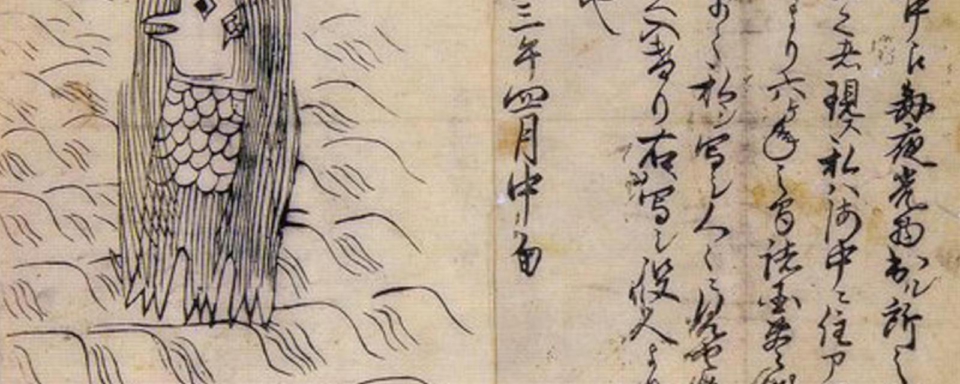

Largely forgotten for generations, Amabie, as it’s known, is an auspicious yokai (a class of supernatural spirits popularised through Japanese folklore) that was first documented in 1846. As the story goes, a government official was investigating a mysterious green light in the water in the former Higo province (present-day Kumamoto prefecture).

When he arrived at the spot of the light, a glowing-green creature with fishy scales, long hair, three fin-like legs and a beak emerged from the sea.

Amabie introduced itself to the man and predicted two things: a rich harvest would bless Japan for the next six years, and a pandemic would ravage the country. However, the mysterious merperson instructed that in order to stave off the disease, people should draw an image of it and share it with as many people as possible.

This curious encounter was promptly published in the local newspaper, accompanied by a woodblock print of Amabie’s likeness, which helped to disseminate its image across Japan.

For much of the past 174 years, Amabie has remained rather dormant. But as the coronavirus has swept across Japan, its image has recently resurfaced on social media, bringing hope that those who share it are helping to end the current pandemic.

“Amabie can be seen as an Edo Period (1603-1868) meme,” said Victoria Rahbar, a graduate student at Stanford University’s Center for East Asian Studies. “Amabie tells the public to draw [it], and then make that drawing go viral to prevent the plague.”

According to Google Trends, the mythical yokai resurfaced in early March and its popularity has since spread to five continents, with the #AMABIEchallenge hashtag now appearing in English. In addition to the tens of thousands of paintings, drawings and personalised depictions of Amabie on Twitter and Instagram, people in Japan have begun selling face masks and hand sanitisers with Amabie’s image on them.

One illustrator who daubed Amabie’s likeness on the side of a long-haul lorry tweeted an image of it, saying, “I travel all over the country with my [goods] and Amabie to pray for the disease to go away.”

Other Amabie-lievers have made edible Amabie sushi and baked Amabie-shaped biscuits. The yokai has found itself embroidered on fabric, blown up as a balloon animal and made available as a charm in Japan’s ubiquitous gachapon (capsule machines). People are even dressing up their pets as the sea-born spirit.

Though yokai can also be monsters or demons, these folkloric spirits are well-loved across Japan today. Some, such as Amabie, possess benevolent powers. Others are shape-shifters, and many are typically portrayed in outlandish forms with elaborate backstories. There’s karakasa kozo, a bouncing one-eyed umbrella who sneaks up on people and licks them. Biwa bokuboku is a self-playing lute that performs in the street and begs for money, and tofu kozo is a timid kimono-clad, man-child known for following people home and offering them tofu.

Yokai originated in the Edo Period, and until the early 20th Century, it was common in Japan for newspapers to report local yokai sightings as big events. Historically, yokai were rather feared, but in recent generations they have taken a friendlier form.

“Yokai often play the role of helping people process unpleasant feelings or situations. They can sometimes be a kind of pressure valve for when things get tense,” said Hiroko Yoda, co-author of the book Yōkai Attack! The Japanese Monster Survival Guide. “What gives them weight is their long history. Yokai, in various forms and names, have been part of Japanese culture for centuries. Today, yokai are mainly a form of entertainment. They are commonly used as characters in video games, anime and comic books.”

Similar to the comfort brought by the popular mascot Kumamon following the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake, Amabie’s resurgence has brought a sense of levity at a time of great uncertainty. One possible explanation for this is the connection between yokai in Japanese society and the country's native polytheistic Shinto religion. In fact, it’s not uncommon for yokai to take on religious roles. The shapeshifting kitsune fox yokai, for instance, is traditionally believed to be the messenger of the Shinto god Inari, and statues of it adorn Shinto shrines throughout Japan.

“Yokai are the carriers of historical memory of the Japanese people,” said Rahbar. “They are not static, with new ones popping up occasionally thanks to new documentation of them being found or due to the work of [Japanese manga] masters like Shigeru Mizuki,” whose manga franchise GeGeGe no Kitaro helped to not only revive yokai characters in the 1960s, but also to transform them into more lovable and less-feared characters.

Ironically, Mizuki Productions played a role in reviving Amabie’s popularity during the current pandemic. On 17 March, the company tweeted an illustration of Amabie with the message, “May the modern-day plague go away,” prompting other manga artists, such as Mari Okazaki, to post their own illustrations with similar messages of hope for the end of the pandemic.

“There is a lot of dark news at the moment,” Okazaki said. “I think people who see all of that want to enjoy themselves.”

“When people paint or draw, it tends to calm them down, so people are drawing [Amabie] for both themselves and others,” Okazaki continued. “Various artists are participating in the fun, which I think is a good thing.”

Japan's Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare has recently gotten involved with the newfound Amabie craze. In a tweet on 9 April, the government agency shared an image of the yokai reiterating Amabie’s original sentiment and encouraging people to “prevent the spread of the virus.”

Amabie may be just a fictional figure, but spreading its image is helping to bring light and togetherness in a time when people are looking for connection and hope. Okazaki’s own depiction of Amabie is a colourful creature powerfully rising from the sea, overshadowing a dark, demonic figure lurking in the background.

“There are many types of yokai in Japan, from cute to scary. I think the figure I’ve drawn is a reflection of my heart,” Okazaki said. “It is a manifestation of my feelings – my way of saying, ‘Please protect the people.’”

Latest Stories

-

Tema MCE initiates emergency repairs on deplorable harbour road

26 minutes -

GH¢1m saved as NSA purges payroll of 2,000 ghost workers

27 minutes -

‘If I were the president, I would have sacked Sammy Gyamfi right away’ – Kennedy Agyapong

31 minutes -

Mahama nominates 4 more MDCEs in Accra

37 minutes -

Today’s Front pages: Friday ,May 16, 2025

43 minutes -

BoG statement on OTC withdrawals was timely – Ghana Association of Banks

1 hour -

Fuel prices to witness biggest drop of 8% today, May 16 due to cedi’s appreciation

1 hour -

PUWU urges government to renegotiate IPP contracts to curb revenue losses

2 hours -

GITA, NUSPAW sign pact to improve working conditions of seafarers

2 hours -

Africa-CDC Director-General lauds Mahama’s leadership in healthcare delivery

2 hours -

Second Ghana Automotive Summit 2025 launched in Accra to promote locally assembled vehicles

2 hours -

FirstBank collaborates with Rotary Club to commission Berekuso Community Clinic

3 hours -

Needless Immigration and Police Checkpoints crippling the Volta Region

3 hours -

Forestry Commission engages industry players ahead of timber licensing regime

3 hours -

Constitutional Review Committee engages journalists, social media community

3 hours