Audio By Carbonatix

This past summer, the global trade regime finalised details for a revolution in African agriculture. Under a pending draft protocol on intellectual property rights, the trade bodies sponsoring the African Continental Free Trade Area seek to lock all 54 African nations into a proprietary and punitive model of food cultivation, one that aims to supplant farmer traditions and practices that have endured on the continent for millennia.

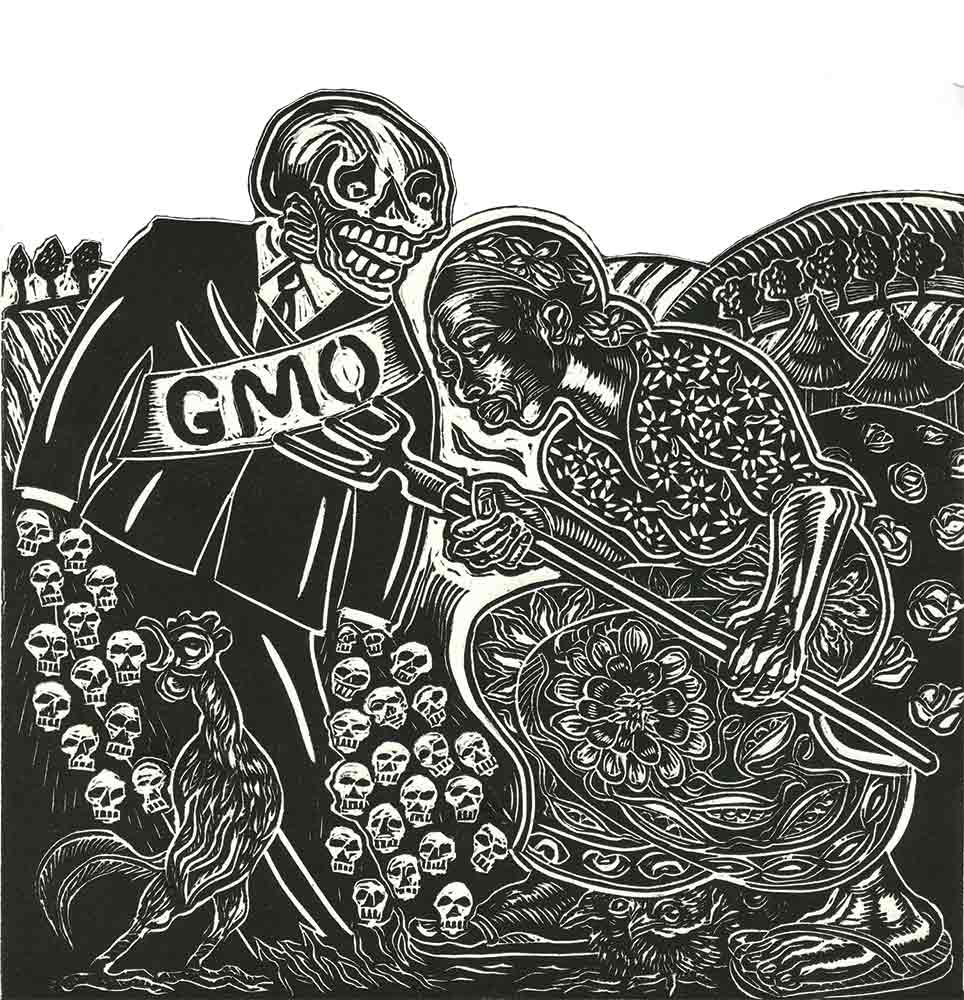

A primary target is the farmers’ recognized human right to save, share, and cultivate seeds and crops according to personal and community needs. By allowing corporate property rights to supersede local seed management, the protocol is the latest front in a global battle over the future of food. Based on draft laws written more than three decades ago in Geneva by Western seed companies, the new generation of agricultural reforms seeks to institute legal and financial penalties throughout the African Union for farmers who fail to adopt foreign-engineered seeds protected by patents, including genetically modified versions of native seeds. The resulting seed economy would transform African farming into a bonanza for global agribusiness, promote export-oriented monocultures, and undermine resilience during a time of deepening climate disruption.

The architects of this new seed economy include not only major seed and biotech firms but also their sponsor governments and a raft of nonprofit and philanthropic organizations. In recent years, this alliance has cannily worked to expand and harden intellectual property restrictions around seeds—also known as “plant variety protection”—under the fashionable policy mantra of “climate-smart agriculture.” This broad rhetorical phrase conjures a suite of practical, climate-driven upgrades to food production that conceals a vastly more complicated and contentious effort to reengineer global farming for the benefit of biotech and agribusiness—not African farmers or the climate.

The tightening of intellectual property laws on farms throughout the African Union would represent a major victory for the global economic forces that have spent the past three decades in a campaign to undermine farmer-managed seed economies and oversee their forced integration into the “value chains” of global agribusiness. These changes threaten the livelihoods of Africa’s small farmers and their collective biogenetic heritage, including a number of staple grains, legumes, and other crops their ancestors have been developing and safeguarding since the dawn of agriculture.

For the farmers who are in the path of a global market crusade to standardize and privatize their seeds, the stakes are simply the preservation of their right to economic self-determination. In early 2023, I spent several weeks traveling in Ghana’s far northern savanna and meeting with farmers who are the supposed beneficiaries of “improved” patented seeds. With a dry season that lasts up to eight months and worsening droughts, the region would seem a poster child for agricultural programs ostensibly motivated by climate and humanitarian concerns. Yet in village after village, farmers received and discussed the details of the new Western-backed seed regime with wariness, confusion, and anger.

Early one morning, I joined a gathering of seven farmers inside an adobe municipal building on the outskirts of Paga, a market town near Ghana’s border with Burkina Faso. The group had convened at the invitation of Isaac Pabia, the 45-year-old national secretary of the Peasant Farmers Association of Ghana. When he isn’t tending his cowpea and cassava crops, Pabia travels the country to update his fellow farmers on policy changes affecting smallholder agriculture, still the most common livelihood in sub-Saharan Africa.

At the top of Pabia’s agenda was a rumor about provisions in the country’s 2020 seed law. Early reports indicated that politicians in Accra had criminalized the saving, sharing, and trading of seeds among neighbors or at local markets. Word was spreading that farmers who shared seeds protected by patents—a concept as foreign to most of them as the genetically modified seeds the patents protected—could be sent to prison. Farmers were particularly worried about the government’s expected decision to green-light a genetically modified variety of the cowpea, a staple of West African diets. Was it possible, the farmers asked, that Ghanaian police could be empowered to imprison cowpea farmers for trading and refining “unregulated” native seed stocks?

“The law is real,” Pabia explained in the local language. “It was written by the companies to control how we use our seed.”

Picking up a copy of Ghana’s Plant Variety Protection Act—based on the same draft law as the proposed African Union protocol—he shifted to English and read Section 60, which stipulates penalties. “A farmer who willfully commits an offense,” he read, enunciating slowly, “is liable on summary conviction to a fine of not less than five thousand penalty units… or a term of imprisonment of not less than ten years and not more than fifteen years.”

The room fell silent as the information settled in the minds of the group. Farmers in northeastern Ghana have been cultivating the cowpea—a protein-rich legume that North Americans know as the black-eyed pea—since the Bronze Age. How was it possible that people continuing to farm in that lineage, some 5,000 years later, could face 15 years in prison for infringing property claims on crop varieties based on the local original

That question didn’t come up during Vice President Kamala Harris’s whirlwind trip through Ghana, Zambia, and Tanzania in late March—the highest-level visit from a US official since the White House released its strategy paper on sub-Saharan Africa the previous summer. In all three countries, Harris reaffirmed that document’s pledge to fight food insecurity and “boost” agricultural production on the continent. At a Zambian farm, she announced $7 billion in public-private investments aimed at bringing “new technologies [and] innovative approaches to…the agricultural industry.” These would be delivered, she said, by partnerships involving “African leaders, African corporations, US corporations, nonprofits, [and] philanthropists.”

Harris did not mention these actors by name or specify what manner of “innovation” she and the US international aid complex intended to bring to African farms. Instead, she invoked the beguiling, technocratic vision of “climate-smart agriculture” as a rationale for dramatically restructuring the region’s food economy.

Ghana’s Plant Variety Protection Act is a national variant of a regional and global crusade to integrate every aspect of smallholder farming into the industrial food system. The crusade’s most stubborn opponent has been the humble seed, whose natural ability to replicate has made it uniquely resistant to proprietary control. Since the 1980s, agribusiness, its sponsor governments, and its mega-philanthropy allies have targeted this stubbornness as though it were a tumor, using national laws and threats to push governments throughout the Global South to introduce patent-protected hybrids and genetically modified organisms, or GMOs. The most direct beneficiary of this plan is the four-company oligopoly that controls half the global seed market and 75 percent of the global agrichemicals market: Bayer (formerly Monsanto), Corteva (formerly DowDuPont), BASF, and Syngenta, a subsidiary of ChemChina.

Development-minded agronomists have touted chemical- and capital-intensive agriculture as the panacea for world hunger since the Green Revolution began in the 1960s. But the specific case they’ve made for replacing peasant-cultivated seed varieties with patented versions developed in foreign laboratories has morphed over the decades. Today’s rhetoric pivots on alleged concern over “food security” in an age of climate change. Western governments, led by the United States, routinely deploy this language as they advocate seed “improvement” in countries like Ghana, which in the summer of 2022 became one of the roughly half a dozen sub-Saharan African nations to permit the sale of GMOs, alongside South Africa, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and Kenya.

“We can’t accept this law,” said Faustina Banakwoyem, a 35-year-old soya and pepper farmer and the only woman in the Paga group. “The companies will try to entice us by saying their seeds are ‘better.’ Then we’ll become dependent on seeds that you can’t replant. Our seeds are from this soil. It’s colonialism to say what seeds we can use and how to use them.”

“The companies have changed our food culture; now they are using threats to change our farming culture,” said Joseph Karimenga, a 30-year-old farmer of pepper, onion, and maize. “If we replace traditional seeds with foreign seeds that can’t be replanted, what happens if the new seeds don’t arrive? When people are afraid to share seeds with their neighbors? It’s an attack on our survival.”

Ever since the first plants became eligible for limited patent protections in the 1930s, the drive to expand intellectual property claims on all living organisms has continued apace. But it’s only recently that these claims have held any meaning outside of the United States and a handful of European countries. The global debt crisis of the 1980s allowed Washington to condition aid and loans on state disinvestment in agriculture, clearing the way for Western agribusiness to enter markets in Africa and elsewhere. The same countries were at the center of the project to globalize Western patents through the World Trade Organization, which at its founding in 1995 mandated that member nations “provide for the protection of plant varieties either by patents or by an effective sui generis system or by any combination thereof.”

Agribusiness firms with biotech divisions were especially keen on establishing a foothold in Africa, home to an agricultural sector that the business press touted as the “last great frontier” and valued in the trillions of dollars. To introduce African farmers to their seeds and agrochemicals, the companies teamed up with Western governments to establish public-private collaborations. The most significant of these was the West African Seed Alliance (WASA), a joint project of the US Agency for International Development and agribusiness giants such as Monsanto and DuPont Pioneer that worked with governments to “transform West African agriculture” by increasing access to “improved seed varieties, fertilizer and crop protection products,” according to USAID’s main contractor in the program, an industry-allied aid group called Cultivating New Frontiers in Agriculture.

But the companies faced a problem: Throughout the mid- and late ’90s, concerns about the potential health and environmental harms of GMOs fueled a fast-growing countermovement dedicated to slowing their spread. In the Global South, this movement deployed a new language of “farmers’ rights” to confront an increasingly strident Northern discourse of “plant breeders’ rights.” Groups resisting the top-down imposition of GMO seeds and input-intensive agriculture came together within La Via Campesina, an international network founded in 1993 to assert “the right of peoples to define their own food and agriculture systems.” With that group, the concept of “food sovereignty” was born. So, too, was a movement to defend this idea against the globalizing agenda of the World Trade Organization. “When the WTO TRIPS [Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights] Agreement required some form of privatization of seeds, it put a Damocles sword over a lot of people’s heads and forced them to figure out how to deal with it,” said Renée Vellvé, one of the activists whose work preceded the founding of La Via Campesina.

The nascent movements for food and seed sovereignty scored a key victory in 2003, with the signing of the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety. An addendum to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, the agreement required signatory nations to adopt biosafety laws and regulatory agencies to oversee the testing, production, and sale of GMO crops. The protocol instantly curbed the rush toward a genetically modified Green Revolution in Africa.

“If not for the protocol, it would have been a free-for-all to take over important commodity crops in Africa and elsewhere,” said Mariam Mayet, the executive director of the African Centre for Biodiversity. “The companies would have registered GMOs under laws for conventional seed. There would have been no discussion around biosafety, no regulation. They didn’t want the protocol [because] it was a signal by the international community that GMOs are different and present risks.”

The pro-GMO alliance realized that it needed a better promotional strategy for the post-Cartagena era. New industry-aligned donor groups soon emerged to clear legal hurdles and personally win over African officials, scientists, and regulators (if not yet actual farmers). The Rockefeller Foundation had brokered cruder versions of such alliances during the Green Revolution of the mid-20th century—a simpler time for the surgical deployment of US aid and know-how in the Global South—and now it updated the playbook. In 2001, Rockefeller officials met with executives from five major seed suppliers, including DuPont Pioneer, Monsanto, and DowAgro. This gathering hatched the African Agricultural Technology Foundation, which served a role that was similar to that of the West African Seed Alliance, but with a focus on African agronomists and researchers instead of politicians. “The AATF was designed to forge partnerships between biotech firms and African scientists,” said Joeva Sean Rock, an anthropologist at Cambridge University who studies the politics of West African agriculture.

Soon after its inception, the AATF attracted the attention and largesse of a new and ambitious player on the global philanthropy scene: the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The foundation—which had formerly promoted neoliberal domestic policy causes like school privatization in the United States—was in the midst of consolidating a new image as a fount of charitable giving in Africa, funding antimalarial initiatives and other public health campaigns. In 2007, the Gates and Rockefeller foundations partnered to launch the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa(AGRA) to turbocharge the legal and political transformation sought by the AATF and WASA, a project it described as “both an economic and moral imperative.”

That imperative was anything but self-evident to small farmers in the Global South. Just after Gates launched AGRA, more than 500 seed and food sovereignty representatives convened in Sélingué, Mali, for Nyéléni, a forum called by La Vía Campesina. The gathering represented the maturation of a movement that was now “firmly on course,” said Renée Vellvé of GRAIN, an international alliance of small farmers that was a forerunner to La Vía Campesina. “Nyéléni brought together peasant organizations, fisherfolk, Indigenous peoples, and food workers to frame ‘food sovereignty’ and forge strategies around it.” The following year, 200 African groups representing 200 million small-scale farmers organized the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA) to face down the chemical-industrial food system being promoted by AGRA, which GRAIN accused of “imposing a corporate-controlled seed and chemical system of agriculture on smallholder farmers, appropriating Africa’s indigenous seed varieties, weakening Africa’s rich and complex biodiversity, and undermining seed and food sovereignty.”

Under the tutelage of industry donors, more African governments established rudimentary regulatory frameworks for the introduction of GMOs. By the mid-2010s, companies were racing to apply for the first trial permits to grow GMO varieties of regional staples (cowpea, sorghum) and global commodity crops (maize, cotton). In Ghana, farmers had started to hear worrying reports from neighboring countries that had fast-tracked GMO approval. To the north, cotton farmers in Burkina Faso bemoaned the shorter fibers of Monsanto-patented GMO cotton seed. To the east, Nigerian farmers were dismayed by the quality of an allegedly pest-resistant cowpea variety engineered to produce high levels of Bacillus thuringiensis, a soil bacterium.

“They said the taste of the GM cowpea is not as nice, and that it takes longer to boil and doesn’t stick together when making moi moi [a traditional cowpea dish],” said Joseph Karimenga, the Paga cowpea farmer. “When black-market shipments of the cowpea started appearing in Ghanaian markets, we learned that everything they said was true.”

In defiance of the concerns of small farmers, the drive to spread GMOs across Africa was boosted by a 2012 G8 initiative, the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition, which matched 10 African countries with Western aid agencies and companies like Monsanto, Syngenta, and Yara, the Norwegian fertilizer giant.

AGRA, meanwhile, expanded its charm offensive among African officials and global investors. It beckoned the latter with the unofficial slogan of AGRA’s longtime president, Dr. Agnes Kalibata, who liked to tell audiences, “Come for the food security, but stay for the economic opportunity.”

Such appeals rang hollow for the smallholding farmers who make up more than 60 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s population. In Ghana, popular opposition in 2013 defeateda proposed biosafety law that would have allowed GMO trials to proceed, as well as the first attempt to pass a punitive seed law. “We educated and sensitized people about the laws by engaging with traditional authorities—the chiefs—that have more legitimacy and command more allegiance than members of Parliament in Accra,” said Willie Laate, the deputy executive director of Ghana’s Centre for Indigenous Knowledge and Organizational Development.

The chiefs also proved more influential than the highest-profile Green Revolution evangelist at the time, US President Barack Obama. During several visits to Africa, Obama lectured Africans on the benefits of GMOs during promotional events for Feed the Future, an agricultural project that dovetailed with his administration’s Doing Business in Africa Campaign.

Fuseini Bugbono, a 64-year-old cowpea and cassava farmer in northern Ghana’s Gundoug Nabdam district, laughs at the memory of Obama’s forays into African agriculture. “Obama came here saying GMOs are good, but his family had an organic garden behind the White House!” he recalled. “All of the Western leaders are like hunters who use poison. They don’t eat that meat. They sell it.”

By the start of Obama’s second term, the alliance to industrialize African agriculture had stepped up its PR offensive, largely thanks to the money and strategic direction of its de facto leader, Bill Gates. Among the group’s new agitprop efforts was an agriculture-themed reality makeover show on Ghanaian television that AGRA produced between 2015 and 2017. Each episode depicted farmers gratefully receiving expert instruction on the superiority of “modern” inputs and practices. According to a study by Joeva Sean Rock, the Cambridge anthropologist, more than half of the shows centered on the promotion of “improved” seeds that were bred and patented abroad.

The biggest Gates-funded communications projects are independent of AGRA. The Open Forum on African Biotechnology in Africa, or OFAB, holds seminars for scientists, farmers, and various influencers in African states with relevant pending legislation. Last year, the Ghana office organized a workshop with senior Muslim clerics to explain why the GMO cowpea was halal. Operating along similar lines is the Alliance for Science, headquartered at Cornell University, which networks with graduate students, scientists, and journalists in contested African countries. As with OFAB, the Gates Foundation is its largest funder, to the tune of $22 million. Much of that outlay supports a fellowship program that brings young influencers to Cornell’s Ithaca campus for all-expenses-paid three-month residencies to “empower emerging international leaders” to advocate for “access to scientific innovation in their home countries” and master techniques for “effective communications around agricultural biotechnology.”

Nine thousand years ago, give or take, Mesoamerican farmers bred the first maize cobs from a wild grass that grew thick in the river valleys of central Mexico. They were followed by farmers further to the south, in what is now Guatemala and Honduras, who developed other maize varieties around the time African farmers began to cultivate the cowpea. These ancient crop breeders did not know of each other’s existence, but their descendants have been drawn together into a global movement to defend the genetic survival of their agricultural inheritance.

This fight has reached the most isolated corners of maize’s expansive “region of origin,” such as Concepción de María, Honduras, a village high in the mountains near the country’s southwestern border with Nicaragua. Most residents are Indigenous or mestizo descendants of early maize breeders, eking out livelihoods on tiny mountainside plots that look down on fertile, well-irrigated valleys devoted to commodity crops owned by land barons such as Porfirio Lobo Sosa, the corrupt former Honduran president, who signed his country’s hated seed law in 2012.

A dirt road winding uphill from the village square leads to the shack office of the Association of Ecological Committees of Southern Honduras. For a decade, as the battle over the seed law gathered momentum, the tin-roofed structure served as the war room where a wiry farmer named Feliciano Castillo Avila led the local resistance to it. Recalling the protests with a reporter today, the 58-year-old Avila, normally earthy and quick with a joke, turned somber and businesslike at the mention of what he will always call “the Monsanto law.” (In 2018, the German conglomerate Bayer paid $63 billion for Monsanto and its scientific assets.)

“The law attacked our patrimony, our right to feed ourselves,” Avila said. Opening a desk drawer, he removed a manila folder marked “LEY UPOV,” or “UPOV law,” a reference to the Geneva-based, industry-dominated NGO that drafts model “plant variety protection” laws for the Global South. Avila’s file contained a dog-eared, soil-stained printout of Honduras’s 2012 Law for Protection of Plant Varieties. He flipped a few pages and handed me the document.

“Section 51,” he said.

Like Section 60 of Ghana’s seed law, this was the part Honduran farmers knew best: the one listing the criminal penalties for infringing on patented seeds, either by selling or sharing them, or via “an unauthorized invention process” resulting from accidental contamination. Unlike Ghana’s seed law, Honduras’s UPOV legislation contained no direct mention of prison. But Avila understood the stipulated fines—up to “10,000 days of income,” or 27 years’ worth of subsistence farming income—as a tool for achieving something even worse: dispossession.

“The high fines are a tactic to deprive farmers of their land,” he said. “We’d choose jail before selling our farms. At least in jail you eat three times a day.”

Because the national media was silent on the law, Avila came to understand the gravity of its draconian language and intent only after conferring with a farmers’ collective in Colombia. “The Colombians invited us to a meeting and warned us, ‘Stop this law or you’ll be seriously screwed,’” Avila said. “They also had experience with transgenic seeds and explained how they don’t reproduce like our peasant seeds.”

Returning to Honduras, Avila organized a meeting in the mountains. Five thousand farmers showed up and drafted a statement rejecting GMOs and the Law for Protection of Plant Varieties. “We rose up and refused to recognize the law,” Avila said. “We filed lawsuits. We formed seed banks to ensure that our seeds would always be accessible for communities.”

In the fall of 2021, the Honduran Supreme Court struck down the seed law in a decision that cited the farmers’ rights enshrined in the national Constitution and in the UN Declaration of the Rights of Peasants, adopted in 2018. That document is a nonbinding statement that dedicates an article to affirming peasants’ human right to manage seed over the claims of trade agreements and patent laws. It was adopted along strict North/South lines, with most of the G8 countries fiercely opposed.

A bloodier version of the Honduran story played out in Guatemala in 2014, when a similar seed law sparked the wrath of the country’s battle-hardened and well-organized left agrarian movement. For 10 days, farmers brought Guatemala to a standstill, shutting down a major highway and gathering in cities and towns across the country. “Peasants understood the severity of the situation, making things much more complicated for the government and the companies,” said Inés Cuj, the soft-spoken director of the Meso-american Permaculture Institute, an organic farm and political education center on the shores of western Guatemala’s idyllic Lake Atitlán.

Cuj maintains a small memorial to these protests in her institute’s seed bank. On a wall lined with clay jars containing the region’s seed heritage—including dozens of red, black, and white maize varieties—she’s posted a photo depicting a phalanx of tiny and fierce-looking Indigenous Maya women. Dressed in traditional pink blouses and headdresses, they stand with their children facing down a line of armored riot police with truncheons raised.

“These women rejected government claims that companies only want to make our seeds ‘better,’ because our seeds do not need improvement,” Cuj said. “Our ancestors made them strong over thousands of years. They want to create dependence on seeds that must be bought every year and that don’t reproduce. Have you tried using the seeds of GM maize? The plant comes out deformed. It half-grows, and it dies.”

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is by far the biggest funder of initiatives aimed at the transformation of African agriculture. With $63 billion in net assets, Gates arrives in most African countries with equal or greater standing than many heads of state—never mind CEOs, aid agency directors, and other foundation officers.

Befitting its founding role, the Gates group is the leading funder of AGRA, accounting for more than $650 million of the agency’s $1 billion budget since 2006. (Adjusted for the five-year strategy it announced in September, the number is likely closer to $950 million.) Gates’s money is also the main source of support for the Open Forum on Agricultural Biotechnology in Africa and the Alliance for Science, two extensive communications initiatives promoting GMOs on the continent. The Gates Foundation’s support for the African Agricultural Technology Foundation—totaling $141 million since 2008—has outpaced the $97 million spent by USAID, the group’s second-biggest funder. During this time, at least $46 million of the AATF’s budget has gone directly into the coffers of its top contractor, Bayer (formerly Monsanto).

Stacy Malkan, the cofounder and managing editor of the research group U.S. Right to Know, believes that the foundation’s lavish support for these groups is part of a not-so-virtuous cycle reflecting its direct—and often overlooked—material interest in agricultural biotechnology and the industrialized food system generally.

“At the Gates Foundation, its investments are the program,” Malkan said. “American taxpayers are subsidizing, via tax deductions, billions of dollars of investments that grow the foundation’s endowment. The so-called charity arm of the foundation funds industrial agriculture in Africa in ways that benefit the companies the foundation is invested in.”

It’s not clear what other interests the foundation’s outlays are serving. AGRA, Gates’s flagship Africa operation, has been a resounding failure by its own self-proclaimed altruistic metrics. Last February, an independent review commissioned by the Gates Foundation found that AGRA had made no significant progress toward its goals of doubling the yields and incomes of 30 million smallholder households and cutting food insecurity in half. After 12 years and more than $1 billion spent across 11 countries, hunger grew in Africa, while crop yields barely moved. Critics say this was a predictable outcome of AGRA’s policies.

“If the target is food security, ‘improved’ seeds for a narrow set of commodity crops miss the mark entirely,” said Timothy A. Wise, a senior adviser at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy and the author of Eating Tomorrow: Agribusiness, Family Farmers, and the Battle for the Future of Food. “Hybrid and GMO seeds are engineered to grow with optimal water and large quantities of synthetic fertilizer, which small-scale farmers don’t have and can’t afford. Even when higher yields are achieved, monocropping depletes the soil and displaces more nutritious and important crops.”

In 2022, possibly in recognition that its ambitious revival of the Green Revolution was a failure, AGRA dropped the loaded historical reference from its name to become a disembodied acronym. “It is appropriate that AGRA now stands for literally nothing,” Wise said.

AGRA’s subtle rebrand occurred amid a broad shift in messaging in the donor-driven precincts of agricultural development policy: the emerging mandate to combat “food insecurity” by adopting “climate-smart agriculture” (CSA). The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization coined CSA in 2009 to describe practices aimed at increasing farm resilience and reducing the carbon footprint of a global food system responsible for up to 37 percent of annual greenhouse gas emissions. Since then, however, observers say that CSA has been usurped by the Gates-led corporate alliance, with programs like Water Efficient Maize for Africa serving as green-painted Trojan horses for industry.

“CSA is an agribusiness-led vision of surveillance [and] data-driven farmerless farming, [which explains why] its biggest promoters include Bayer, McDonnell, and Walmart,” said Mariam Mayet of the African Centre for Biodiversity. “From a climate perspective, it entrenches the global inequalities of a corporate food regime. There’s no system shift at all.”

Octavaio Sánchez, the grizzled director of Honduras’s National Association for the Promotion of Organic Agriculture, contends that policies that promote true resilience must focus on regenerating soils through the use of organic fertilizers, crop rotation, and the preservation of native seeds able to adapt to changing conditions. These are the cornerstones of a global agro-ecology movement that has emerged from the seed and food sovereignty coalitions of the past three decades.

The peasant-led agro-ecology movement—with La Via Campesina and AFSA in front—rejects the familiar refrain from agribusiness promoters that it is condemning farmers to permanent poverty and stagnation. The movement’s position is supported by both a growing literature of case studies and the development of scientific agroecological practices. When Gates Foundation officers were preparing to launch AGRA in 2006, researchers at the University of Essex published a study showing that agro-ecological practices increased yields by an average of nearly 80 per cent across 12.6 million farms in 57 poor countries. The authors concluded that “all crops showed water use efficiency gains,” which led to “improvements in food productivity.” The UN’s High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition recommended in 2019 that governments support agro-ecological projects and redirect “subsidies and incentives that at present benefit unsustainable practices,” a judgment based on similar studies undertaken around the world.

Pivotal to the success of sustainable food systems under local control, say agro-ecology advocates, is winning the battle for control of seeds. “Bill Gates’s ‘magic seeds’ will accelerate the cycle of chemical destruction that has destroyed the earth’s soils in less than a century,” said Inés Cuj, the permaculture institute director in Guatemala. “The answer to climate change lies in traditional knowledge and ancestral seeds that have been around for thousands of years. We cannot allow the attack on them to succeed. It is an attack against life itself.”

Latest Stories

-

Adom FM’s ‘Strictly Highlife’ lights up La Palm with rhythm and nostalgia in unforgettable experience

2 hours -

Ghana is rising again – Mahama declares

5 hours -

Firefighters subdue blaze at Accra’s Tudu, officials warn of busy fire season ahead

6 hours -

Luv FM’s Family Party In The Park ends in grand style at Rattray park

6 hours -

Mahama targets digital schools, universal healthcare, and food self-sufficiency in 2026

6 hours -

Ghana’s global image boosted by our world-acclaimed reset agenda – Mahama

7 hours -

Full text: Mahama’s New Year message to the nation

7 hours -

The foundation is laid; now we accelerate and expand in 2026 – Mahama

7 hours -

There is no NPP, CPP nor NDC Ghana, only one Ghana – Mahama

7 hours -

Eduwatch praises education financing gains but warns delays, teacher gaps could derail reforms

7 hours -

Kusaal Wikimedians take local language online in 14-day digital campaign

8 hours -

Stop interfering in each other’s roles – Bole-Bamboi MP appeals to traditional rulers for peace

8 hours -

Playback: President Mahama addresses the nation in New Year message

9 hours -

Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union call for strong work ethics, economic participation in 2026 new year message

11 hours -

Crossover Joy: Churches in Ghana welcome 2026 with fire and faith

11 hours