We met

What would Joseph have said or written about Pharoah? What eulogy would he have given about the man who had literally stepped aside and put him, Joseph, a complete stranger, in charge of managing his empire.

In the beginning, mine was a simple: to be a ‘damned good lawyer’ who is able to feed his family. His was a big dream: to build a world class law firm, right here in Accra.

Little did I know, that just like Joseph, my dream would come to pass when I helped another discover his larger, bigger dream.

And it was as if it was all by providence. I was a student at Legon when my friend Joey (now Bishop Joel Obuobisa), invited me to play the piano at a breakfast meeting organised by the then very young Lighthouse Chapel, at a restaurant in Osu.

Joey sang. I played. It was just our routine. I played. He sang. Bishop Dag Heward-Mills preached. I had played for the Bishop several times when he came to preach at Legon on Friday nights. I had convinced myself that he probably liked my playing because he was a keyboardist too.

At the end of the sermon, there was, of course an altar call. No one came up, but ONE bespectacled man in a dark brown political suit, with arms folded. ‘Who comes to the Lord with folded arms?’ my mind said to me, as I did my job.

I played, as he accepted Christ. At the end, I packed up and went back to Legon. I didn’t even know his name.

Fast forward to 1992. I was out of school and needed a job quickly. I went to my first choice law firm, clutching my application letter, CV, certificates and several written articles in my hand. I was made to wait at the reception for three days.

They didn’t even take my envelope to show to the big man. I never got an interview. I spoke with my classmate, Francis Botchway, now professor of law at Qatar University.

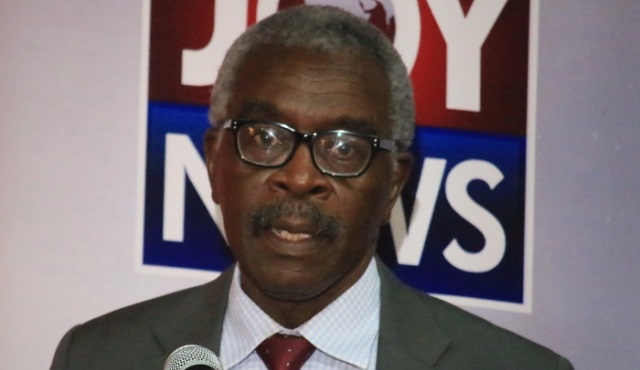

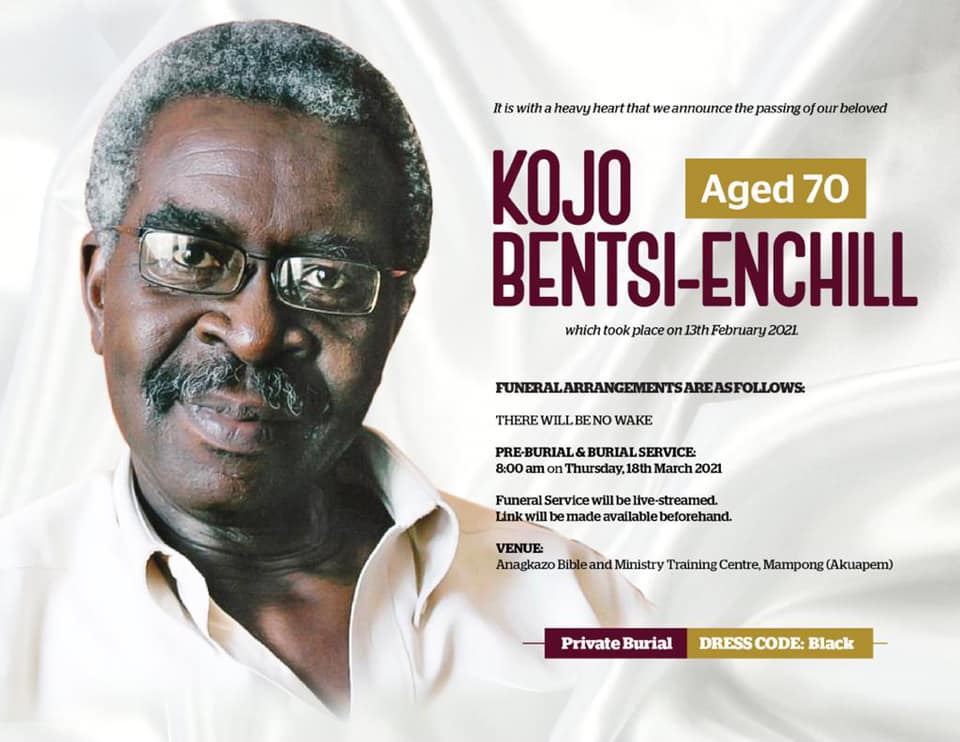

He told me about a ‘new’ lawyer in town, someone called Kojo Bentsi-Enchill with an office at Osu. And so to Osu I went, with the same material.

Watch this: someone had made me wait for three days; I didn’t have to wait for 30 thirty minutes for Kojo. He came out, himself, to invite me into his office.

That was the man who accepted Christ with folded arms! I didn’t tell him that then. We spent the next hour doing something we have done for almost thirty years – ARGUE.

We had two key disagreements at our first meeting. ‘Mr Bentsi-Enchill...,’ I started. He cut in: ‘My name is Kojo. And your name is Kojo.’

Here was a then 41-year-old man, asking a 24-year-old whipper-snapper, just-out-of-school, wet-behind-the-ears, wannabe lawyer, to call him by his first name, O.K.

The next was when he asked why I chose his law firm. How was I going to tell him that he was my second choice. So I lied. I said it was because his office was only one taxi ride from my house.

He cut through my rubbish: ‘your answer failed, the only question you have flunked during this interview.’ That is how it started. And that is how it continued for almost 29 years.

We thought

Kojo taught me how to think and the power of independent thought, that law wasn’t just about regurgitating what you read, but what you thought about it, and how all of that solved the client’s problem.

I was not allowed to present ‘bland letter law’ to him. I would get ‘RUBBISH’ written in his favourite red ink across the paper.

I had to think outside the box, analyse across the form, assess beyond the template, examine the matter over the matrix and then break the mould with my position.

He didn’t just encourage polite disagreement on everything, he seriously demanded it, as long as it was properly informed. I learned to concede when I was wrong. He would show me why.

I would go back and reconsider. Rewrite. He was as profuse with praise as he was with criticism. So if I was right, he would accept it after the argument, and shower unrestrained praise and, ultimately, bonuses and promotions.

Years later, he would return my work with no comments. I was concerned. I asked why. He said, ‘I don’t need to, anymore.’

We research

He taught me how to research. Thorough, detailed research. If there were 30 thirty cases on a matter, he wanted ALL of them. Why? Because that case that you might leave out might be what the other side might bring up. You ought to be ready to distinguish it if need be.

You dare not cite headnotes of cases to Kojo! It was a cardinal and almost unpardonable sin.

Three steps: first, you read the actual words of the judge; second, you render them in your own words; and, third, you quote the judge. Headnotes? In KBE’s work?? Are you out of your mind?

If there were no authorities on the matter, that was GREAT because it gave us the opportunity to be inventive, creative... and naughty. But I needed to be sure that there was no authority.

I just couldn’t start by my own postulations. ‘Your ideas aren’t the law, young man! We can’t bill the client for this,’ he would snap when I presented woolly, fuzzy work based on nothing but hot air.

He it was, who first pointed me to Justice Taylor’s aphorism that the three yardsticks of the law are statute, case law and well-defined practice.

We wrote

He taught me how to write. It was always ‘structure before prose,’ and he made me set up the skeleton of every argument or memo before populating it with the narrative.

He beat it into me: ‘skeletal, Ace, skeletal. First, show me where you are taking me to; second, take me there; and third, tell me where you just took me.’

We digitised

Digital law and e-practice are and remain one of the secrets of the firm’s immense success, and the details of which will remain our secret. When he asked me to start computer classes, I had the audacity, impudence and temerity to tell him I was a lawyer and not a secretary.

He responded, ‘young man, if you know what is good for you, you will go to the computer class right now.’ I went grudgingly and got bitten by the bug. Months down the line, he had to drag me out of the computer training school.

I had finished the agreed courses and started learning programming without permission. In an August 2003 interview with Nicholas Thompson of Legal Affairs, a New York online magazine, I said of Kojo’s sheer obsession with digitising and digitalisation: ‘The product is where it is because my partner is crazy. Any sane person would have given up years ago.’

He never stopped referring me to that. When he struck this path, literally no one believed in it. Now we all know better.

We worked

I returned to the firm from school in 1995. We worked long hours. Overnight if need be. You go home in the morning, have a shower, grab breakfast and you are back at the office.

You learned that 24 hours is a long time, and that there is a lot that you can achieve if you spaced and paced yourself well. We billable packed hours into our days. Five years after I returned to the firm, I made Partner. Ten years later, I was Managing Partner.

Now I tell everyone that I am ‘semi-retired’ as Senior Partner. I often accused him of being responsible for all I have become as a lawyer. He had the same response every time – he would sweep his eyes over me, upon and down, wag his finger to follow his gaze, and say ‘I deny being responsible for anyof this.

What happened to the ‘nice’ young man who came looking for a job at reception?’ I would always deny the ‘nice’ part.

When he tapped me to lead and restructure what is now the Disputes Department, I didn’t have a clue what to do as I had done precious little litigation practice before then.

But his advice was very simple: ‘It is just law. Treat each matter like a transactional or advisory matter.

Do your checklist and pay attention to the details. And depend on DKD.’ I did. Worked like magic. But I would go out there and make mistakes, fight too hard and get into the inevitable brawls in court.

He sometimes would receive complaining calls on stuff I had done while in court. When I crossed the line (and God knows I cross the line as often as I breathe), he would ignore me for a while.

When it got too much, we would have discussions. He would allow me to wax defensive, ranting and raving. Never judgemental. Next time, try this or try that. Leading. Guiding. Grooming. Correcting. Shepherding.

Then he would add: ‘go and give them hell!’ He always allowed me to be me. Thank you, sir!

Ten years ago, when he handed the firm over to me to run. I told him that I would feel accomplished if I achieved half of what he had achieved.

Ten years afterwards I have also handed the firm over to another of Kojo’s protégés, Seth Asante, to run. Seamless transition.

As if nothing has happened. We know that we look and see far because we have stood on the shoulders of a giant.

He cared

The rest is personal, and it could fill a book. He loved me and loved my family. He was there when I named my kids. When in October 1995 I came to the office after I had dropped my wife, who was at the first stages of labour, off at the hospital, he walked me out of the office.

Working with Kojo was not all easy all the time. There were difficult days. But he always kept his word. I stayed. It was not all about work. I liked the man. He liked me back. Scratch that.

I loved the man and he loved me back. Fiercely. And that was it.

So, I had a small dream. He had a bigger dream. He could have built something small and personal, which would have given him fabulous personal riches and not much of a legacy.

But he was built for something bigger and better. That’s why in his life time, he saw and shepherded two successors and has left a legacy that speaks for itself, not just the building, but the sheer number of lawyers who have wet their feet, cut their teeth, blooded their talent and shaped their lives and careers within his dream.

In helping him achieve his dream, I probably have achieved mine. I am proud that he considered me somewhat of a cross between a son, a much younger brother and disciple.

Our 29 years of knowing each other was also wrapped in music. I played when he met the Lord, when he dedicated the Firm to the Lord, when we dedicated the new building to the Lord… we would spend long periods discussing music.

He was classical music and hymns man, playing by the book and taking the courses. I was and am the shortcuts guy, breaking the rules and improvising on highlife, jazz and bebop. In several ways our music styles typified our relationship: we were like chalk and cheese (me being the chalk, of course). He preferred his work with left justification.

I preferred mine with full justification. I said his didn’t look professional. He said mine didn’t look natural. He could type faster than any human being I have seen. But I insisted I could type faster. He shunned the limelight. I hugged it. We were different. We just blended easily.

The end

Several months ago, I went up to his office on the fifth floor with my usual note pad and list of items to be discussed. ‘I have come for wisdom,’ as I would usually say. He stopped me.

He informed me that the doctors have confirmed ‘it’ was not going to work out. I had lived in denial for about a decade. I wept like a baby. He comforted me.

I mourn his passing but I celebrate his life, the life of the man I didn’t know before our first meeting, but who became my Father [in the law], my Brother [in life], my Pharoah [in work] and co-music hobbyist [in fun].

We spoke Fante, but today my tribute is in three Akyem appellations:

Kunkuroamoa – a powerful and irrepressible one

Okuntunkununku – a great one who does not break his oath

Ammᴐ-so-ansan – never goes back on his word

Nanti yie na da yie.

Latest Stories

-

William Amponsah sets new national record in the men’s 10,000m

19 minutes -

TGMA Artiste of the Year: A battle of two Kings and a Living Stone

23 minutes -

Whoever leads NDC with Mahama’s record will beat any NPP candidate – Quashie

38 minutes -

Margaret Naana Ackom confirmed as first female DCE of Gomoa East

38 minutes -

Musah Dunkwah explains key figures behind NPP’s defeat in 2024 elections

56 minutes -

Scientists find ‘strongest evidence yet’ of life on distant planet

60 minutes -

OR Foundation’s support sparks spontaneous jubilation among Kantamanto traders

1 hour -

Van Dijk signs new Liverpool contract

1 hour -

Trump administration threatens Harvard with foreign student ban

1 hour -

I want to be a trailer driver – Viral ‘humble’ trotro mate seeks support to enroll in driving school

2 hours -

Mahama invites Sahel Military leaders to ECOWAS summit – Ablakwa

2 hours -

JMJ, Jah Lead hint at new collab after resolving feud

2 hours -

French jails have come under attack. Are violent drug gangs to blame?

2 hours -

Guidance and Counselling Association launches counselling body to promote national well-being

2 hours -

Anlo youth council congratulates newly appointed MDCEs of Anlo state

2 hours