Dawn yawns, and the Moon is still some hours away from completing its nightly shift.

But the inhabitants of Vamboi, a small village near Tumu that barely registers on the map of Ghana’s Upper West Region, are already up, their eyes drained of what little sleep remained in them when they first blinked open.

There isn’t any evidence of national electricity supply in sight – there wouldn’t be for years, in fact, such is the sheer remoteness of this place – with the little generated by a vehicle’s battery on this night powering a black-and-white television, to which the village-folk are now drawn like flies to a juicy piece of fruit.

And it’s for one man that they’re gathered, a fellow each of these natives – like the millions of other Ghanaians, regardless of status or age, also keeping wake at this very moment – absolutely adores, admires, and reveres: Azumah Nelson.

The boxing Professor is about to deliver a lecture, a flawless lesson in ‘the sweet science’, to one of the many opponents he outwitted and floored with such stunning technique and consistency in his heyday. The spectators in Vamboi cheer him so loudly you’d think he could actually hear them, all the way from his spot in a ring on the other side of the Atlantic.

Someday, one of those watching – tiny Fentuo Tahiru Fentuo – would tell him all about it.

Nearly three decades later, Fentuo has established himself as one of Ghana’s eminent sports journalists, so acclaimed that he is recognised even by the greats – including his childhood hero, Nelson, who he met up with for an exclusive interview only last year.

That reputation has been acquired during a combined eight years spent working with two of Ghana’s biggest media-houses, the Excellence In Broadcasting (EIB) Network and Omni Media Limited.

It’s a long way from his very modest beginnings – more than 500 miles away, at the other extremity of the country – and Fentuo, regardless of how much farther life and his career takes him from those roots, remains grounded and conscious of the improbable success his journey has been thus far.

He takes none of it – no milestone attained or peak reached – for granted.

“I was born as the first of my parents’ offspring but with five [half]siblings,” Fentuo, 34, tells Ink & Kicks‘ Yaw Frimpong.

“Ours was as poor a home as you’d find anywhere, ticking all the boxes that define the worst of what poverty could be, from rationed and nutrient-deficient meals to extreme child labour – you name it.”

Education, as you might imagine, wasn’t particularly high on the agenda in Vamboi. Earning a livelihood meant working on the farm, and you were never too young to lend a helping hand. As the firstborn – a son, too – Fentuo was, by default, a human resource of immense potential value to his father.

“To have a boy as your first child was considered a big blessing.”

“Above all other things, my worth as an asset was going to be determined by how much I contributed as a farmhand, and expectations were certainly high. For starters, though, I had to do errands – fetch water, bring a cutlass, herd the cattle, this and that – as soon as I could steadily place one foot in front of the other.”

It was pretty much the same for every family.

But some of that changed, quite significantly, in 1991, when the 31st December Women’s Movement (DWM) put up the village’s very first school, a Day Nursery. Suddenly, there was a fresh incentive for parents to consider the prospect of formal education.

It wasn’t so straightforward, though, as some needed persuasion to enrol their wards, even as fathers – the sole decision-makers, traditionally, in what is very much a patriarchal society – were urged to volunteer a child each towards assembling the inaugural batch of pupils.

And that included Fentuo’s dad, who, at the time, had just one child.

“Surely, he had every reason not to heed that call – and Lord knows there were more than a few who tried to get him to decline – as, after all, others who had children in the tens could afford to send half of them to the school and barely feel the pinch on the farm.

“The odds were stacked against my father – and, thus, against me – but, ultimately, he made the difficult decision to take me to school.”

Fentuo made it just in time for the day of the school’s commissioning, an occasion to be graced by no other personality than the then First Lady of Ghana – who doubled as Founder of the DWM – Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings.

With a nursery full of children, and a charge to put on a proper show, the teachers got to work, teaching the kids basic nursery rhymes.

Fentuo, they found out to their delight, was a natural.

“I was quite good at those,” he says. “And that, perhaps, was where my lifelong interest in the English language begun.”

He was one half of a duo picked to perform those well-rehearsed rhymes for the sufficiently impressed First Lady and her entourage; Nuratu, a cousin, was the other. Fentuo hasn’t forgotten that day, the most vivid recollection he retains of an otherwise unremarkable childhood.

“I remember the reaction after I was done performing ‘A Lion’,” he recalls.

“I was no older than five years, yet I could see that everyone present – my beaming father, especially – was really proud of me. Oh, there were people from neighbouring villages as well. The atmosphere was almost like what you could expect to feel at a political rally.”

And maybe it really was, unofficially, some sort of rally.

The general elections, Ghana’s first since mid-1979, were coming up the very next year, and Mrs. Agyeman-Rawlings’ husband, Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings, was reportedly eyeing a transition from military dictatorship to become the first democratic president of Ghana’s soon-to-be-born Fourth Republic (he hadn’t publicly declared his intentions just yet, but not long after he did, those ambitions were realised).

Fentuo would appreciate all that years later, only with the benefit of hindsight. What he did know for a fact back then, though, was that this event presented him with a first opportunity to see a 4×4 vehicle (“lots of them,” he is thorough enough to point out) and to sit in one – the pick of the bunch, in fact.

“Mrs. Agyeman-Rawlings took Nuratu and myself in her car after the programme and proceeded to ‘campaign’ in other parts of the district, before bringing us back to our village.”

His face, as he tells that story, appears as radiant as it must have been while he enjoyed that ‘presidential’ treat. And it lasted a fair few days, before all that joy was replaced by creases on his rather prominent forehead – and for good reason.

“We had been told the day’s events would be on national television not long afterwards, hence, each evening found us gathered around Mr. Dintie’s battery-powered TV, hoping to catch the news item and bask in the glow of it.

“Yet weeks passed with nothing in sight, and my father – every bit as disappointed as myself – eventually stopped taking me on those news-watching, thrill-seeking visits.”

The first day they didn’t show up, as fate would have it, was just the day the news report they so eagerly sought aired on Ghana Television (GTV).

“Some of the older folks had sent one of my cousins running to our house to inform my father about the ongoing broadcast, sending us running almost immediately in the opposite direction.

“We couldn’t get down there soon enough, however; by the time we arrived, breathless yet full of spirit, the focus of the news broadcast had shifted.”

Fentuo had missed out on a chance to see himself on television, but it wouldn’t be his last appearance on that medium. He didn’t know it then, but Fentuo would spend much of his adult life in the news – more specifically, chasing the news and telling the world about it.

“I enjoyed watching the news every evening,” he says. “While every kid always seemed to crave something else on TV, the news was all I ever wanted to see.

“I loved the news.”

The vicarious satisfaction felt as his son took the stage, drawing so much attention and applause, stayed with Fentuo’s father for quite a while, long after the fanfare had dissipated.

He needed no more convincing that Fentuo’s place was not on the farm, but in school – although many, including some who had earlier tried to sway him the other way, gave him a good nudge anyway – and was now determined to keep him there, even at considerable personal expense.

Before long, Fentuo had outgrown Vamboi – with respect to his academic progress, that is.

“Promotion to Primary One took me to a school in another village, nearby Bugubelle.

“Nearby isn’t quite an accurate adjective, I guess, given that required trekking three-or-so kilometres on foot – barefoot, I mean.”

Walking on the grass on the edges of the road, on really hot days, was a little gentler on his baked-and-crusted soles than the scorched earth.

Conditions – surprise, surprise – weren’t much better in school.

“The classrooms had no furniture, thus demanding that we lay on our stomachs to write. And for lunch, after school was over, we would head right back to the farms where our labouring parents were – and it was also there that we spent our weekends, helping out, with work on Sundays proving particularly gruelling.

“Junior Secondary School (JSS) – as it was then called – was only slightly better,” he continues the story of his journey up the educational ladder, “in that we actually had chairs to sit on.

“But that’s if you consider two concrete blocks stacked on top of another two as ‘chairs’; for tables, we had to stack up a little higher, topping it all with a slab of plywood for an appreciable degree of smoothness when writing!”

If this is all beginning to sound a bit like some CNN documentary about life in rural Africa, that’s because it’s very much a reflection of reality.

And Fentuo lived it – every stark detail of it.

“We only had two teachers, one of whom – teaching Mathematics and Science – fell sick throughout almost the entirety of JSS, returning only in our final year to prepare us for the Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE).”

That already-compromised preparation was further undermined by a lack of access to any text-books at all – a situation that partly accounted for the shambolic results of previous batches, including the failure of entire classes.

The only hopes of better fortunes Fentuo and his colleagues had, incidentally, came from those same underperforming predecessors.

“All we had for study material were notes handed down by some of those who had completed school years prior; the prospects, from whichever angle one assessed them, were pretty daunting.”

It wasn’t about to get any easier, at least not for Fentuo.

“A week before we embarked on the trip to Tumu, the district capital, for the BECE, a bizarre sequence of mishaps while on the farm worsened my plight.

“It was during the dry season and pasture for the cattle was hard to come by. In a bid to offset that deficit, we climbed trees to cut leaves to feed them.

“And that’s how I found myself lodged among the boughs of one tree, attempting to bring down a particularly leafy branch that was agonizingly close to where my right foot was planted. All it took was one bad swing of the cutlass and, before I knew it, its blade firmly sunk into one of my toes.

“The excruciating pain that followed was terrifying enough, as you can probably imagine, but my horror was complete the very moment I saw the extent of damage done to my foot: the affected toe was hanging only by a tendon or two, as warm, thick blood oozed out from the wound.”

Fentuo grimaces at this point, as though experiencing the injury all over again.

“The only thing greater than the intensity of my pain was the sheer magnitude of my panic. Alarmed at the sight, I lost balance, slipped, fell off the tree, and landed on – wait for it – my wrist, badly twisting it as a result!”

So there he was – in the worst possible shape, with a severed toe and a sprained wrist, just days before the most consequential week of his life up until that point.

How much worse could it get, really?

“Why,” Fentuo says, “that was exactly what I thought, too!”

Apparently, that was all the motivation he needed to hop (literally) onto a bus on the next market-day, the only day Fentuo and his just-as-nervous classmates could secure adequate transportation to Tumu.

Their anxiety wasn’t without reason. The performance they’d put up in the upcoming exams would, to a very significant extent, determine the course of the rest of their lives.

The exams took place on the campus of Kanton Senior Secondary School (KANSEC), Tumu, with the candidates quartering in the school’s dormitories; ten papers in all, written over the course of five days.

On each of those days, one particular boy looked a little odd.

“To say I was conspicuous would be an understatement. I couldn’t wear shoes on both feet, for obvious reasons, but I certainly wouldn’t have anyone think it was because my parents couldn’t afford a decent pair – which is why I wore one shoe, and carried the other along in my hand.

“Speaking of hand, I was fortunate it wasn’t my preferred one that was limp, hence I had no trouble at all writing the papers in full.”

Exams over, the wait began.

“It was the longest I’d ever been away from school, but I was hardly at a loss as to what to do with all that free time. I immersed myself into working on my father’s farm, even though neither my stricken hand nor foot had healed enough.

“Not that I had much of a choice. It was unbelievably difficult work but, without it, my fees on entering Senior Secondary School (SSS) wasn’t getting paid. In doing it for my dad, then, I was really doing it for myself, such was my confidence that I’d pass the exams.”

And pass he did – even if by slender margins – before gaining admission to a second-cycle institution, but only because he had chosen the ‘right’ one.

“KANSEC — mentioned earlier — was my first choice, a moderate one, because its cut-off aggregate was perched at a relatively low-hanging 30, a mark I only narrowly beat; all the better schools within range, like Nandom Secondary School or St. Francis Xavier, had much higher standards and were thus harder to get in.

“As it happened, my teachers, who had helped me make my picks, simply did not believe I was good enough to make it into any of those more prestigious schools – well, thank goodness for their lack of belief in this particular matter!”

Fentuo’s grades may not have been outstanding, but they did see him seal his place as a member of just three graduates of Bugubelle JSS, Class of 2001, to advance to SSS that year.

The remainder?

“Well, some rejoined the school to give it another go… while others just gave up trying.”

Fentuo, though, was only getting started, building momentum to navigate the next phase of his life.

The spark would come from his Form Master, who, on the very first day of school, came clutching a list. On it, he had the names and aggregate scores of each student in that class of 50; no prizes for guessing who had the worst tally of the lot.

He had something else, though, a message tailored – and delivered primarily – to a clearly embarrassed Fentuo.

“He said something so profound it has stuck with me ever since, after calling out each name and the accompanying figure: “Here, your BECE results don’t matter,” he started. “I know some of you came from deprived schools, but this is your chance to prove that your poor performance is no true reflection of just how intelligent you are”.”

That message, from that day onwards, became his constant source of inspiration, and it wasn’t long before Fentuo – the runt of the litter in almost every sense, so physically small that he was nicknamed ‘Aperture’, a reference to the tiny camera hole – was outdoing them all.

“I was a really popular student in secondary school: considered generally intelligent, consistently finishing among the top three, and rarely – if ever – beaten in the twin subjects of English and Literature.”

He didn’t stop there, so unrelenting in trying to prove his worth that he went the whole nine yards, sparing no effort even in extra-curricular activities.

“I was secretary of the Debaters and Drama clubs, winning inter-school debating competitions for the school and starring in inter-school drama contests, thoroughly enjoying all of that.”

Not all his memories of KANSEC were fond, though, with Fentuo falling foul of the rules more than once and surviving disciplinary issues that – for all his good work – could well have truncated his stay on campus. If ever he pens his memoirs, you’d probably get to hear more about those rather unsavoury tales.

Back home, all wasn’t well.

“My father, around this time, had met the woman who’d become his second wife, and was no longer very nice to my mother or to myself. There were nights I cried because a request for money to fund the purchase of gari or some other basic provision never received a favourable response – or, often, no response at all.

“Sometimes, I’d protest, but it didn’t get me anywhere. No longer the supportive dad, there were times he even went as far as daring me to quit school and come join him on the farm if I felt so strongly about the stalled supply of financial assistance from home; after all, it wasn’t like the family had a long or rich history of schooling.”

Those words stung, as did his mother’s lamentations about how she was being maltreated, whenever Fentuo returned for the holidays.

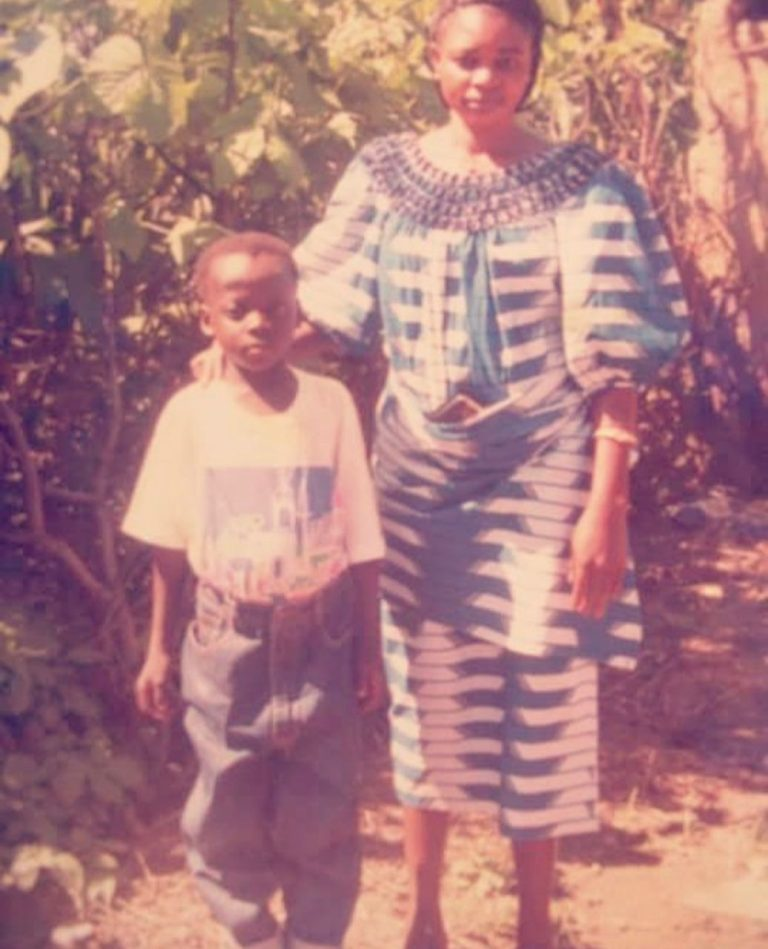

The good woman did more than burden her son with details of her plight, though; like every caring mother, she was determined to – out of her limited means, sometimes supplemented by small loans – see her son across the finish line, making sure he was always in the right frame of mind to study.

That was an expression of love Fentuo would never lose appreciation for.

“The kind of parents I had were not those who’d drop you off at school or attend Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) meetings; Mother and Father, in fact, had no idea where my school was located. It hardly mattered, anyway, as I did not even know having your parents visit you in school was a thing – in much the same way the idea of celebrating birthdays, for instance, was alien to me.

“If they could afford money for school fees – and both certainly did their bit – you could be absolutely sure they loved you to the moon and back.”

Fortified by that knowledge, Fentuo pressed on and thrived, even if circumstances were far from ideal, eventually finishing among the best six students of the 191 KANSEC presented for the Senior Secondary School Certificate Examination (SSSCE), along with Mustapha, his bosom friend and study partner throughout school.

“There were still a few grades that could be bettered, however, and a Bolgatanga-based brother of mine (now deceased), was kind enough to aid me in registering for private exams. And so I made the not-so-short trip to his place, in the Upper East regional capital, where I was to sit for the papers.

“While there, I was involved in his cement business, leaving me with barely any time to study. I took the exams anyway, and although I didn’t perform as well as I might have, I achieved the required improvement, trimming my final aggregate from an okay 16 to a quite respectable 13 – a significant leap, too, from the blush-inducing 27 with which I had entered SSS just three years prior.

“I had made my inspirational Form Master proud. And yes, I did feel immense pride, too, in myself. One more corner, though not with any ease, had been turned.”

On to the next.

“Everyone seemed to have a pretty fair idea – a consensus, really – about where that next step ought to lead: a career as a teacher or nurse, after attending one of the many training colleges dotted around the country.

“Many people told my parents that the university would be a total waste of my time and of their resources, that I would struggle to get a job after school if I went down that path. At the training college, they rightly reasoned, I would receive a tidy allowance and be in a position to take care of them even before I was done with school.”

But that was their idea, not Fentuo’s.

He knew they had a point, especially when not a single person from his village had ever been to the university. And, indeed, he was convinced to jump on the ‘training college’ bandwagon… just not for long enough to actually go through with it.

“I did apply to the Navrongo Nursing Training College. It was the only form I bought, but, by the time the admission arrived, I had made up my mind that I was not going to become a nurse. My decision wouldn’t be reversed, in spite of all the well-meaning counsel that came my way; on university life was my heart set.

“For me, it was that or nothing.”

It didn’t matter that Fentuo would have to wait another year to ensure his dreams came true, or that he’d have to move farther away from Vamboi than he ever had – or even that such a relocation would mean settling for rather inconvenient living arrangements.

“I travelled to Kumasi – outside of my home region, for the very first time – where I moved in with my brother, a labourer who lived with his wife in a single-room apartment. They’d just had their second child so, well, I’d leave the situation to your imagination.

“I took up work as an untrained teacher, after first helping my brother with his sand-winning job. This, mind, was at a time all of my former classmates with good grades had already commenced their tertiary education, some of whom were at Kumasi’s Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST).”

That couldn’t have been easy to take, especially when he was teaching kindergarten kids for a meagre salary of GHC20 per month. Fentuo couldn’t have been pleased with his lot, but he remained patient and hopeful, comforted by the prospect of better days ahead.

And, soon enough, those days arrived.

“When application forms were released for the next university academic year, I quickly made my move, with just one school in mind: the University of Ghana (UG), Legon, primus inter pares.

“It wasn’t just because I believed it was (and still is, in my humble opinion) the best in the land, but I also wanted to get as far away as possible from my KANSEC colleagues who were then schooling at KNUST. If I was going to trail them by a year – which, well, was already the case – I’d rather do it from a comfortable distance than suffer the ignominy of sharing the same space with them.”

The universities in Cape Coast (UCC) and in the North (UDS) would have served that purpose, too, so Fentuo applied to those as well. But, of course, there was only one he really wanted, no?

“The UG offer came first, and, from then on, I didn’t care much about the others – even though, yes, they also accepted me.

“My excitement about moving to the famous Legon campus overflowed, and I couldn’t help but express it to anyone who asked… or didn’t.”

Eighteen-year-old Fentuo was certainly ready when UG opened its gates to him.

“I got on a bus to Accra, with luggage fully packed and a heart brimming with anticipation.”

There was some apprehension as well.

Reaching Accra from Kumasi was the easy part; navigating his way through Ghana’s biggest metropolis – without a mobile phone, never mind GPS technology (still something of a novelty in these parts, back in 2006) – posed the real challenge.

Fentuo would have been well-aware that, in those first days, he was always going to be just one wrong turn away from, as they say, ‘missing road’.

He wasn’t about to.

“I had my brother’s phone number written on a piece of paper, which I tucked deeply inside my wallet. For what it was worth – just to be double-sure, because I was taking no chances at all – I also memorized the digits.”

The instructions, on getting to Circle, that buzzing, beating heart of Accra where most bus stations have their terminals, and where the guy just behind probably wants to snatch your bag off you, was simple: “ask for directions to the nearest Madina-bound trotro and notify the conductor that you’d alight at Legon”.

Simple enough, right?

“Sure, following those instructions did get me pretty comfortably to campus, where I moved right to the Legon Hall, with which I was affiliated. Next was the small matter of finding a place to lodge during my first year of schooling, depending on how I fared during a quite straightforward balloting process – all I had to do was pick ‘Yes’, rather than ‘No’, and I’d be guaranteed a place.”

Only if it were that easy.

“The six or seven people before me had been unfortunate with their ballots, and the alarm bells in my head began to go off. As I prepared to go up, many thoughts raced through my mind, none of them particularly reassuring.

“What if I didn’t get a room? Where would I stay, then? Could my parents afford a hostel?”

Of those three legitimate questions, it was only to the last that Fentuo had anything close to a definite answer, and, needless to say, it wasn’t an answer he liked. His hopes were quickly transported to Nima, a place in Accra he had never even been, where an aunt of his stayed. Would she take him in if his ballot proved the same as those of the ones who’d just gone ahead of him?

All Fentuo had in his favour, as he took his turn, was the gambler’s fallacy. As it turned out, he didn’t need much else.

“I got a room, to my indescribable relief, setting me up quite well for the latest phase of my steadily evolving life. I was ready to go, to make a mark at the nation’s premier university.”

Another room, however, would contribute just as much to the great time Fentuo would have in Legon.

“The TV room on top of Tyme Out quickly became my favourite spot – outside of my room and the lecture halls, of course – because, well, ‘old habits die hard’, right?”

What kept Fentuo glued to the TV, though, wasn’t just the news anymore.

The emergence of England’s Premier League to a global audience during the early noughties spawned a relatively new breed of TV viewers, those with a staunch devotion to one Premier League club or another.

London-based Chelsea was Fentuo’s choice, and for him and his fellow Premier League devotees on campus, the TV rooms – first at Legon Hall, and then at the Mensah Sarbah and Commonwealth Halls where he’d later ‘perch’ – were the temples of worship.

Fentuo, before long, developed a reputation.

“I was a loud-mouthed Chelsea fan by this point, emboldened by the great success the newly-minted Blues enjoyed under Roman Abramovich, and fans of clubs enduring worse fortunes – the Manchester Uniteds, Arsenals, etc. – just couldn’t stand my presence.

“I made a real nuisance of myself,” Fentuo says, laughing.

“Even worse – for them – I often had custody of the remote control, so I could literally regulate their suffering as I wished. Now that was fun, even if I didn’t always get away with it – wait, did I tell you about that time my mischief earned me a hefty slap from some stout fella?”

You’d have to ask him for the full version – more humorous than tragic, I can assure you – when you meet him.

Fentuo ran into a different sort of trouble while still at the university, albeit one not entirely of his fault.

“It happened during one of the Hall Week celebrations that are a big part of campus life. These events last full weeks, with activities outlined for each day. And it doesn’t get much better than Commonwealth Hall’s, specifically their ‘Mr Vandal’ show – that’s what it was called, I think.

“My memory is a bit hazy about the details, but I do recall that there was an assembly of ‘macho’ men for a weightlifting competition. It was staged in the compound of the hall and was a real crowd-puller.”

Fun-loving Fentuo, unsurprisingly, wasn’t far from the action.

“I attended lectures in the morning, and when I returned in the afternoon, the competition was underway. I wasn’t missing it for anything.

“The jeans I wore that day had shallow pockets. Now that I think about it, it was probably meant for females, but I had no way of knowing that at the time and only wore whatever felt comfortable.”

Well, back to those shallow pockets, then?

“Ah, yes…

“So I had my cell-phone – yep, I now had one – in one of the pockets, as I watched the guys flex their bulging muscles. Moments later, I realised the device was missing. I quickly borrowed a friend’s and called my number, and though it went through, no-one picked up.

“After a few more tries, the phone was apparently switched off by whoever had it in their possession. With that, I could only conclude it was missing – stolen, to be precise.”

Missing, yes, but it sure wasn’t ‘stolen’, as Fentuo was soon relieved to discover.

“Not long afterwards, I felt a tap on my shoulder. I turned around to find one of my mates handing the phone to me, but with an admonishment: “take better care of it, bro”.”

Sigh.

Apparently, that friend had picked my pocket as a prank, and though Fentuo had every reason to be incensed over what may well have been construed as an expensive joke, he was only happy to have regained the phone.

And that wasn’t even the best news of his day.

Within minutes of switching it back on, a call – from the most unlikeliest of people, the Dean of Arts – came through.

“Are you Fentuo Tahiru?” he asked.

That question alone should be enough to send chills down the spines of most students, and Fentuo was no different. He could, however, do no more than offer the most logical reply.

“Can you come to the department of English now?” came the follow-up question.

“At this point,” Fentuo concedes, “I was very nervous. I had never prior been summoned thus. In my mind, I was in trouble.”

Subsequent developments, though, would allay such fears.

“As I made my way down the hill from the top of Commonwealth Hall, the Dean called back and asked if I had a passport. I’d never owned one, and after admitting to that much, he told me not to bother coming at all.”

Smart as he undoubtedly is, it didn’t take Fentuo long to figure out what all this could be about.

“Now, if someone of the Dean’s stature changes his mind so quickly about seeing me because I didn’t have a passport, surely, it must involve travel, right?

“So I retorted, almost instantly, that I actually had one, only I didn’t have it with me in school.”

How he came up with a passport in near-record time?

That’s a story for another day.

“After a long pause, the Dean asked me to proceed to the English Department, where I was informed that I had been selected for a one-year exchange program at Elon University, USA, on a full scholarship, and that I needed to initiate the process without delay.”

And that’s all he spent the next few weeks doing. Even so, Fentuo couldn’t but wonder why it was to him, of all the potentially eligible candidates, that this privilege had been handed.

“There was no way of telling if I was the brightest student in the English Department at that time. What I do recall, though, is that I had scored five A’s out of six courses in the previous semester.

“And the Dean had also intimated that I’d “earned” this opportunity.”

America!

Land of the Free… of the Brave… and of a dozen or so sports that Fentuo had either never heard of or had absolutely zero interest in.

And still, once at North Carolina-based Elon, he gulped down the entire American sporting cocktail at a go.

“It was there, at that university, that I first warmed up to the likes of basketball, baseball, and American football. Previously, I’d deemed it all a bore-fest, with too much time spent standing around doing nothing and too little in the way of captivating action.”

Still, as Fentuo soon learned, Americans loved their sport, and it was actually that infectious, soul-consuming fan culture which eventually drew him right in, stretching his horizon as far as sports was concerned. That broadened scope would come in handy a little later in life, after Fentuo returned to Ghana.

“The first year after I touched down, following graduation, was spent doing my mandatory national service in Kumasi, where I taught English Language and Literature in English at Kings College, a private senior high school.”

The nature of that job meant Fentuo had more than enough time on his hands, with which he could engage in other pursuits – and he knew just what he wanted to invest that resource in.

“When I was at Legon, I took up internships during vacations. The first two were at Kumasi-based Kapital Radio, as a regular news reporter. Those experiences, for someone so long enamoured of the media, were thoroughly fulfilling.

“That was where I learned how to write news scripts, edit voices and produce stories, among other skills that would equip me for a lifetime.”

Satisfying, too, were the relationships built there – with people like Listowel Yesu Bukarson, Kojo Akoto Boateng and Nathaniel Abankwah (Natty Bongo) – some of which survived those spells at Kapital and have endured till the present.

“These guys weren’t just on top of their game; they were great human beings, too.”

It really was a no-brainer, then, when a chance to return to Kapital in a part-time role opened up, after reaching out to some of his old friends there. And Fentuo left no ambiguity about just which department he wanted to join this time.

“The only internship I didn’t have at Kapital, my third, was spent at Radio Xtacy, also in Kumasi, where I specifically chose to work with the sports crew.

“I produced their shows, with a certain Kevin Taylor – the Kevin Taylor – presenting; till date, in fact, he still calls me ‘Producer’, albeit jokingly.”

It was that foretaste which had him seeking more on rejoining Kapital, where he’d be racking up internship hours but no cash. Fentuo embraced the gig, even ready to pour the pittance he was receiving as national service allowance into covering the considerable distance between Kings and Kapital.

It made sense to him, anyway, if not to others.

“A number of my teacher colleagues did not think the daily trekking was worth the expense, and urged me to reconsider so I could save what little landed in my coffers each month. Some left for government schools while we were still there, actually, and tried to help me do same with the aid of their ‘connections’.

“I turned it all down.”

Nothing could get him to rescind, really, not even a call from Tumu – the town which, due to proximity to Vamboi, was, for all intents and purposes, home.

“It came from the chief himself, Kuoro Richard Babini Kanton XI, a heartfelt request to come and teach at my alma mater. He explained how my people and my school needed my services, and it was very touching. But, again, I had to decline – politely.”

Why, though, Fent?

Why wouldn’t you simply choose an easier life – the security of staying in your comfort zone, you know, being on the government payroll and all?

“It all goes back to Mr. Dintie’s compound.”

Oh, good old Mr. Dintie again… remember him?

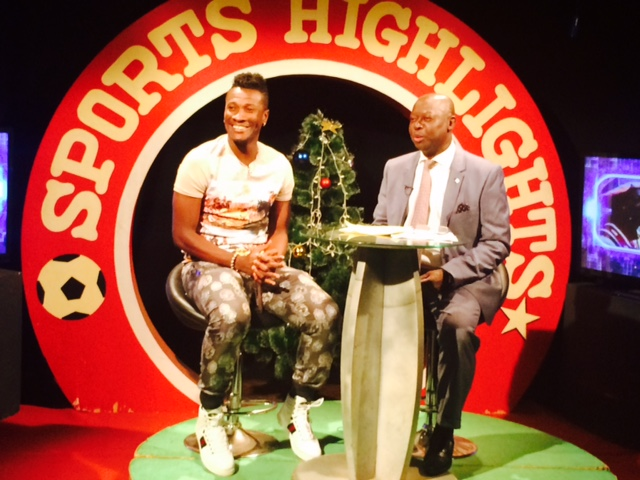

“In those early years watching his television under the bright light of the moon, it was usually the news, Sports Highlights and a bit of Akan Drama. I’ve already said enough about the news, and how I couldn’t get enough of it even at that tender age.

“Akan Drama was more widely-loved, a communal treat, even if only about two or three among us understood Twi; we only needed one of those to be on hand to interpret it for our collective comprehension, and all were pleased as punch.”

Then there was the other programme: Sports Highlights.

“The very first time I watched that show was the day I was inspired to be a journalist.

“Nobody in my social circle – not my teachers or acquaintances, and certainly not my family – had any idea what it would take to get me there. The destination was clear; the route wasn’t.

“Unlike many others who stumbled into a career in broadcasting, I was armed with single-mindedness all the way.

“All the way.”

It was only in secondary school, in Literature class, that Fentuo learned that studying the subject swung open a door to a variety of possible professions, journalism being just one of them.

“Boy, did my eyes light up!” he exclaims.

Guided by that pointer – but still very much in the dark about exactly where to turn next – Fentuo opted to read English at the university, in pursuit of what he figured was the closest thing to a Journalism degree, acquiring practical knowledge and experience during the aforementioned internships.

He was on course, but all that resolve and intrinsic motivation was nearly sucked out of him by unfortunate developments on his latest internship.

“You could imagine my delight when the managers of Kapital called me into a meeting one day and offered to pay me GHC50 for transportation per month.”

And they did – for all of two months.

But then came the blow that well and truly quenched Fentuo’s otherwise blazing zeal, leaving him completely disillusioned.

“There was a time I fell ill and couldn’t go to work for a full week. To my utter dismay, no-one at Kapital called to even check on me. My unrewarded exertions for the station had left me drained, and this was how I was being treated?

“It was a brutal awakening to the fact that I needed to take better care of myself, to prioritise my well-being.”

When Fentuo recovered his health, he quit.

Recovering his passion, though, was going to take a bit longer – but he was in no great haste.

“National service was over, but the school had employed me, so I had just enough on my plate and in my pocket.

“Eight months went by and I got a call from an old friend, Asare Bediako, who had just joined Ultimate Radio from Luv FM.

“He wanted to know why he had not heard me on air at Kapital in a good while. I explained – and thus began the process to bring me to Ultimate as a sports presenter.”

It was, initially, on a part-time basis, but there was precious little not to like about a proposal that offered nearly as much in wages as he was getting for his teaching job. Even better, he got to keep both streams of income.

It felt like being in, um, what’s the word…

“Dreamland,” he says.

‘Fentuo’, in the Sissali language, literally means ‘no name’.

And yet, despite having that as both first name and surname, he has become a household name, one that carries much weight, in the industry. It was at Ultimate, which came under fresh ownership in late 2014 – as part of the EIB Network portfolio – that Fentuo really got to work on carving that niche.

The paint was barely dry on new-look Ultimate when Fentuo was made an offer, one that would demand that he left the classroom firmly behind him and focused fully on the console.

“I did not have to think twice about accepting it,” he says. “It didn’t hurt, of course, that the money also made so much sense. This was my first foray into journalism as a full-time career, starting in January 2015, but I was more ambitious than anxious.”

Assembling some of the best brains in Kumasi’s English radio sphere – a lineup that originally featured Collins Atta Poku, Owusu Bempah (Ayala), Ralph Sarkodie, Kwame Adarkwa, Benjamin Yamoah and Asare Bediako, with Abraham Alokore joining a little later – Fentuo oversaw the launch of the Ultimate Sports Drive.

That project was fun while it lasted – which, frankly, wasn’t very long – and, for its role on his learning curve and as a proving ground, Fentuo looks back at Ultimate and his time there with great contentment.

“I loved working at Ultimate,” he smiles.

“As a partner station of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), there was constant collaboration with that media colossus which afforded me international exposure.

“It was on the BBC Newsday programme that I first appeared, covering one of the most intense press conferences in the history of Ghanaian sport – the infamous one at which The Daily Graphic reporter, Daniel Kenu, asked Asamoah Gyan that apparently provocative question which got him a slap from Gyan’s overprotective brother, Baffour, a day later.”

The game that followed, Ghana’s first since the disastrous showing at the 2014 FIFA World Cup, ended in a draw and saw the Black Stars players booed from the first blast of the whistle to the last. It certainly wasn’t the best of times to make his debut on the BBC’s far-reaching airwaves, but Fentuo made the most of it.

“I also enjoyed working with BBC stalwarts like Matthew Kenyon, John Bennett, Lee James and Ben James,” he says.

But there was another influence, one much closer to home, whose company Fentuo was honoured to keep, a man who did as much as anyone to refine his craft: the late Christopher Opoku.

Opoku first engaged Fentuo in May 2014, instantly helping the younger man to unlock new levels of confidence and prowess he never knew he had, and they were constantly in touch – even working together – until Opoku tragically passed, at 42, nearly three years to the day they first communicated.

“This is a story I’ve told many times,” Fentuo says, the mood of this interview suddenly turning sombre. “My only regret, if any, is that I didn’t get to meet Chris much earlier. There was so much left unlearned and undone by the time of his demise.”

Opoku’s story, to some extent, mirrored Fentuo’s. He had no professional training in journalism when his career started – you wouldn’t have known it, though, would you? – and Opoku also got his big break in Kumasi, before moving to Accra, where the English-speaking radio culture was richer.

Fentuo didn’t have to wait very long for his own chance to make that move.

“One year into my Ultimate stint, Class FM came calling, and I was tempted. Truth is, I had always wanted to work in the Accra media space. As much as I enjoyed working in Kumasi, I always believed, as an English-language broadcaster, that I would never truly reach the limits of my potential if I continued to work in an ecosystem where broadcasting in the vernacular was so predominant.

“I even agreed in principle to the switch, but when I informed my employers at EIB of my decision, they convinced me not to go and gave assurances of better opportunities.”

And so he stayed.

The next opening that came his way, a year later, was too good – too long-sought and too enticing – to let slip, despite the best efforts of Ultimate to keep their man. It was extended by Citi FM – the station where, incidentally, Opoku, his mentor, had spent the final leg of his journalistic career – a place Fentuo had been trying to get into for years.

“In 2010, I applied to do my national service there, went for an interview, but was not called. Then in 2015, before EIB offered me a full-time job, I was considered by Citi as a replacement for the departing Gary Al-Smith – but that, too, fell through.”

Third time, though, proved quite the charm.

“It was a dream come true, although, to be fair, some of it was already quite real to me. On a professional level, I had dealt with Nathan Quao, Godfred Akoto Boafo and Rahman Osman – all of whom I’d be working with on the Citi Sports team.”

Where Fentuo struggled to adapt was outside his new work environment, the wide expanse of Accra that stretched far beyond the station’s Adabraka offices, as he wasn’t finding the adjustment smooth despite having lived three years there in the not-too-distant past.

“But, hey, Accra never gets kinder on anyone, does it?”

Citi, though, certainly did.

“My five years at Citi were amazing, full of growth. In fact, it took only one year for management to consider making me the Sports Editor. The idea was conceived and pitched to me in October 2018, but it wasn’t until 2020 that the decision was finally made.”

Fentuo Tahiru Fentuo – Sports Editor, Citi FM/Citi TV, the complimentary card now read.

It didn’t quite represent the pinnacle, but this was undoubtedly better than anything Fentuo – just two years removed from his first permanent radio appointment – could have imagined his rise to be in such a short time: meteoric, stunning, spectacular.

And, raring to go, he couldn’t wait to prove himself worthy of his new position and the prestige it came with.

“Being editor was a great responsibility, but one for which I was ready, and had been for a while.

“I made changes to some of our major shows, one of which was hosting the Sunday night’s Scorecard myself, and, more importantly, making it audience-centric. We also extended its time slot by half-an-hour. Minor as those tweaks seemed, they paid off in a big way, as the show only blossomed as a result.”

And, raring to go, he couldn’t wait to prove himself worthy of his new position and the prestige it came with.

“Being editor was a great responsibility, but one for which I was ready, and had been for a while.

There were also altogether new developments, like creating a Youtube channel just for Citi Sports, an avenue for disseminating content more easily. These and other innovative measures taken under his leadership ensure that Fentuo leaves the department much better than he found it.

About that, and the excellence and loyalty with which he served, there can be no question.

Television was all Fentuo had eyes for back in his childhood.

“I was often the first to arrive at the Dinties, my scraggly arms responsible for fetching the car battery which breathed life into our little community. I’d do just about anything to have a chance to watch the TV, and perhaps go the extra mile for a front-row seat.”

Radio, though, was Fentuo’s first love.

That was a bit more affordable and accessible – with quite a few households having one – so long as you could erect mightily towering antennas on top of it.

“If the antenna wasn’t long enough, listening to the radio tended to be a rather grating experience, frequently interrupted by annoying static. It was always worse when the wind blew in a certain direction, as we believed it carried the radio frequencies away.

“To increase our chances of catching the clearest signal, we sometimes hung the radio on a sufficiently high tree branch and sat underneath to enjoy.

“But the surest way to achieve clarity was to buy that extra antenna, taping it to the tip of the original one. That was what my father did as we waited to hear news of my BECE results, anyway.”

Radio continued to be a big part of Fentuo’s life, and, in fact, a radio set was the very first thing he bought when, in 2005, he migrated to Kumasi.

As he tried to find a station to listen to on his new set, Fentuo got much more than he’d bargained for.

“My excitement was sky-high, initially, amazed at the sheer variety of stations that I found, after having listened to just one – Radio GBC – all my life, back in the North. I was like a kid in a candy store.”

Then came the culture shock.

“Apparently, that kid was sucrose-intolerant. You see, I arrived with an understanding of no other languages apart from Sissali, my mother tongue, and English, which I’d learned in school.

“Suddenly, though, all I heard on every station I tuned in to was Twi, the main local language. I did not understand a thing.”

Out of seemingly nowhere, however, a saviour appeared.

“My name is Kojo Oppong Nkrumah, and thank you for tuning in to the Super Morning Show on Joy 99.7 FM…,” a voice, belonging to the man now in charge of Ghana’s Ministry of Information, said.

That was the first time Fentuo, aged 17, had heard of Joy, Ghana’s leading English-speaking radio station – albeit via Luv FM, its sister frequency in Kumasi – and he couldn’t listen to anything else. The dial was stuck there.

“I was hooked,” he says.

Mere minutes later, he’d be confused.

“Imagine my bewilderment, then, when I soon heard Anita Kuma introduce her show, Lunch Time Rhythms on Luv 99.5 FM!

“Wait a minute,” I wondered, “who changed my channel? Do radio sets here magically change frequencies when certain programmes end?

“At least, though, the language itself hadn’t switched, so I continued to listen. Thankfully, clarity arrived soon enough, confirming Fentuo still clung to his familiar joy in this peculiar city where he now found himself .

“That was the beginning of my love story with Joy.”

Earlier this week, news broke that Fentuo would be continuing that romance which started nearly two decades ago, following a move to Joy from Citi. It’s unarguably the ‘transfer of the season’, a coup that would surely boost Fentuo’s new team, Joy Sports, one of the more prominent brands under the giant Multimedia umbrella.

To be sure, the decision to cross carpet to join Citi’s major rivals wasn’t an easy one, especially after so long at a place he’d become firmly attached to through thick and thin. But, then again, Fentuo didn’t get this far, so far from Vamboi, by staying where it felt comfortable.

“Nobody likes change,” Fentuo says. “But it is necessary.”

That’s a perspective strengthened by a very recent experience.

“When I left Citi a month ago, the main thing I did was travel. After covering the World Athletics Championships in the United States, I went back to North Carolina, to Elon, to touch base with any old acquaintances I could find.

“I inquired of every single professor whose name I recalled and – guess what? – only one of them was still at post. Everyone else had moved on.

“I cannot say I was surprised but, still, it was a bit of a shock.

“Then a quote from a book I had read on the 11-hour flight from Accra to Washington DC – The Devil and Miss Prym, by Brazilian novelist Paulo Coehlo – struck me.

“A particularly apt portion of it reads: “when we least expect it, life sets us a challenge to test our courage and willingness to change; at such a moment, there is no point in pretending that nothing has happened or in saying that we are not yet ready. The challenge will not wait”.

“So here I am, solely by the Grace of God, embracing this new challenge – and it is my hope that you will join me on the latest chapter of this story.”

Latest Stories

-

Two dead and 65 cases of malnutrition recorded in Bawku for 2024

4 minutes -

NDC’s control of major media houses gave them edge in 2024 polls, says Bawumia

9 minutes -

49th SWAG Awards: High jump Queen Rose Yeboah and Grace Mintah lead nominees for topmost award

23 minutes -

ORAL: ‘National Cathedral spending is an ‘expensive pit of deceit’ – Ablakwa

32 minutes -

Our people didn’t vote – Bawumia explains why the NPP lost

35 minutes -

Dr Bawumia had no choice given Mahama’s decisive victory – Malik Basintale

41 minutes -

ORAL: ‘Clergy were misled by Akufo-Addo’ – Ablakwa on National Cathedral scandal

45 minutes -

‘It is false’- PMMC refutes claims of politicians smuggling gold from Ghana

1 hour -

2 million NPP supporters did not turn up to vote – Kabiru Mahama

1 hour -

IPR Ghana congratulates citizens for peaceful election, calls for unity

2 hours -

Bawumia’s 8 minutes elite ball that zapped the energy of trigger happy politicians

3 hours -

It will be a betrayal if National Cathedral saga does not feature in ORAL’s work – Ablakwa

3 hours -

‘It’s unfortunate we had to protect the public purse from Akufo-Addo’ – Ablakwa on ORAL Team’s mission

3 hours -

Congo lawyers say Apple’s supply chain statement must be verified

4 hours -

Stampede in southwestern Nigerian city causes multiple deaths

4 hours