In the bustling markets of Accra and Ashanti, Ghana, women in the informal sector struggle under the weight of taxes, hidden levies, and daily expenses that eat into their already meagre profits.

Despite their contributions to the economy, these women face challenges that those in the formal sector are largely shielded from.

Through their stories, we uncover the disparities in the tax burden and operating costs faced by women in the informal sector compared to their counterparts in more structured environments.

Tax burden and financial struggles

The narrow alleys of Central Market in Kumasi pulse with life.

Stalls stacked high with second-hand clothes, voices bartering, shouting prices, and negotiating space.

Abrafi Ampomaah moves through the crowd, her eyes flicking between customers as she tries to dodge officials from the Ghana Revenue Authority and the Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly.

This is her reality, as well as other women in the market who struggle to survive in the bustling markets of Kumasi, where the promise of profit is often overshadowed by the weight of taxes and fees that nibble away their earnings.

Abrafi rushes to sit in the stall of her fellow second-hand clothes seller, shakes her head as she counts money in her pocket deciding if she should use the money to either pay the yearly 350 cedi income tax to the Ghana Revenue Authority or the 60 cedis licence fees of the Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly.

Already she owes “railway fee”, a monthly fee traders pay to trade in their makeshift stalls which they occupy on the railway tracks of the Kumasi central market.

Abrafi's voice carries a mix of frustration “It is so expensive to trade here. It is as if I work for the revenue officials. If i give this money to them, trust me, if i do not make sales this week, i wonder if i will survive.

She watches as KMA and GRA officials make their rounds, a familiar presence in the market.

At the Kantamanto market in Accra, the situation is no different.

Ama Fosuaah, a second hand clothes seller, says despite the payment of taxes, they see little development.

"Here at the Kantamanto market in Accra we pay various levies to the Accra Metropolitan Assembly. These go to the government, but we see no improvements here. We built the sheds we occupy to sell. I don’t know what our taxes are used for." Ama explains.

The 60 cedis yearly tax paid to the Accra Metropolitan Assembly, the women say is one of many financial burdens.

Beyond these visible taxes, the women say numerous small expenditures eat into their profits.

These are daily payments to head porters, rent for sheds, and even fees for using market toilets.

As she speaks, she moves to the next stall to ask her colleague for a 2 cedis coin.

This is to pay to use the urinal at the market.

Her voice is filled with frustration as she describes how these costs accumulate.

"Every time we use the toilet, it’s another cedi gone. Many don’t see these as taxes, but they are. We pay for cleaning, light, and security. For the urinal and the toilet, you pay every time you go. These costs accumulate, making it very expensive to operate here."

The Oxfam Inequality Report 2023, affirms informal workers typically don’t pay income tax, as their work exists largely outside of the regulatory framework.

But according to the report it is wrong to say that they don’t pay taxes at all.

There are also a number of other formal and informal taxes that informal workers are likely to pay, such as market fees, permits, or even bribes.

Some of these may go into funding local infrastructure such as public toilets or religious spaces.

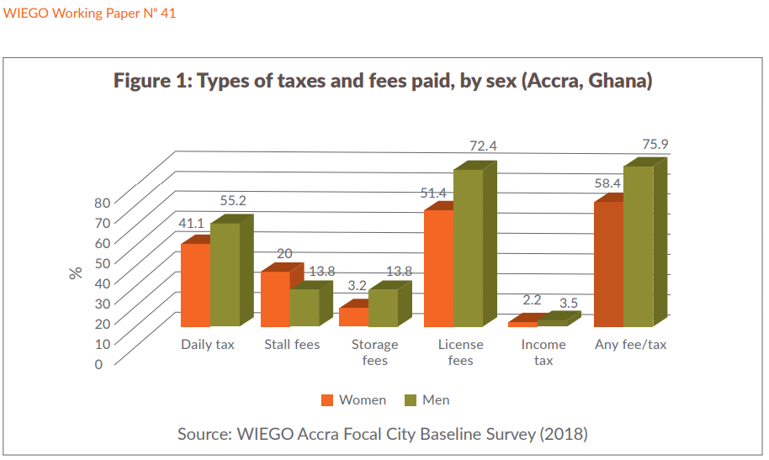

In early 2018, Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) researchers undertook a small survey of informal street and market vendors and kayayei (market porters) in the capital city of Accra.

While the survey was by no means representative of the workforce, the results serve as a useful illustration of why it is important to understand the structure of local tax regimes.

As suggested in Figure 1 below, most informal workers in the sample pay some type of fee or tax to the local government authority (the Accra Municipal Authority).

The two most common are the daily tax (paid by 41 per cent of women and 55 percent of men) and licence fees (51 per cent of women and 72 percent of men).

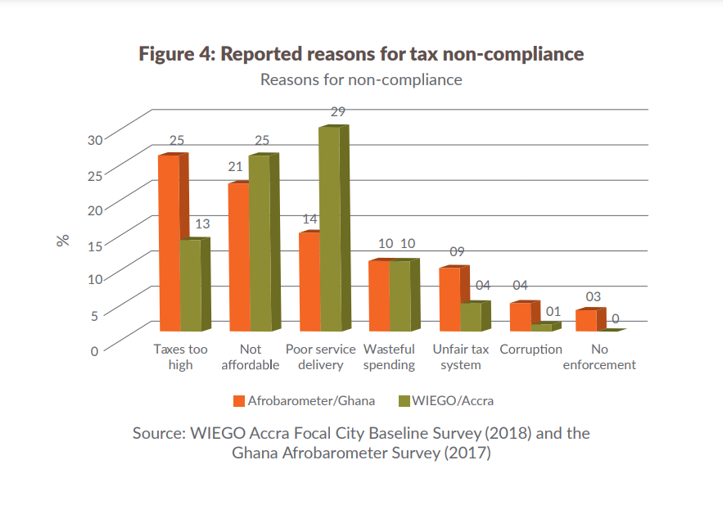

Reasons for non-compliance (Figure 4) also tell an important part of the story.

In the Afrobarometer survey, the single largest reason for not paying taxes is that they are too high.

Negotiating and battling with middlemen and cost of goods

The Kantamanto market in Accra is the hub for the sale of second-hand clothing.

But Georgina Obeng, who deals in thrift clothing at the market, points out the deteriorating quality of goods.

"At first, the bales were not so expensive, but the clothes inside were nice. Now, even the bales priced at 2,000 cedis are full of rags. The importers make everything expensive, blaming high taxes, but the clothes they ship are not very appealing."

The aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these challenges.

"Before 2020, we bought bales for 900 cedis. After the lockdown, prices shot up to 1,700 or 2,000 cedis," Georgina says.

The pandemic’s ripple effects are still felt, with reduced sales and inflated prices making survival in the market even tougher.

Rita Asantewaa also at the Kantamanto Market expresses her frustration with the supply chain.

"The prices of the clothes have gone up. We hear in the news that the economy is stabilised, but that does not reflect in the prices of our clothing. We pay high prices for bales, but the quality is poor, and we often run at a loss."

She shows the exploitative nature of the supply chain.

"The importers and middlemen inflate prices before the goods reach us. We sometimes lose 500 or 300 cedis from our profits because of bad-quality bales. The government needs to intervene. It is as if we are working for the suppliers. Sales are bad, and we cannot even make enough to cover our costs,” she said.

Harassment and insecurity

Emelia Asare deals in African prints at the Kejetia Market in Kumasi.

She imports her prints from neighbouring countries.

Emelia reveals the informal sector’s lack of regulation leads to frequent harassment by security personnel and other authorities.

"Who do you tell when a customs officer takes so much money from you without giving you a receipt? It’s part of the reason many market women suffer in silence. Many traders here at the Kejetia Market work on credit and goodwill, with little to no capital. The market women cannot stand and fight for their rights, as customs officials and middlemen exploit them."

Daily struggles and health Issues

Florence Nagai points out the differences in access to basic amenities.

"In the formal sector, you get access to periodic or annual leave, and you are still paid whilst on leave. They have facilities provided for them, unlike us who pay for everything by ourselves. We do not go on leave. If we decide stay away from the market for one week, we will go hungry"

Rita Asantewaa describes the physical and emotional toll of their work.

"Many second-hand clothing sellers at the markets have developed high blood pressure. The price of the bale is not worth the quality of clothes inside. When we cut open the bales, we become frustrated and sad. There is no job around, so we have to do this work to survive."

For market women, every minute they spend seeking healthcare means lost sales and lower income.

They struggle to balance their health and their work.

Unlike formal workers, who can take a few hours off without losing much money, market women can’t afford to miss even a short hospital visit.

This financial pressure makes many of them choose self-medication, which can worsen their health and lower their quality of life.

The lack of adequate sanitation facilities at the market centres is also a significant challenge to their wellbeing.

The demand for fairness and support

The women in the informal sector are calling for a fairer system.

They want the government and the Ghana Union of Traders Association (GUTA) to address the exploitative practices of revenue or tax collection, importers and middlemen.

They also seek transparency and accountability in how their taxes are used, and equitable access to basic amenities and development projects.

The Women Committee Chair of PSI affiliate of the Union of Industry, Commerce, and Finance Workers (UNICOF) of the Trades Union Congress (TUC Ghana), Ruth Osei-Asante, tells the role of tax justice in improving women’s rights and gender equality.

"Tax laws are there to ensure I pay my taxes. The laws, however, do not indicate the impact of these taxes on me, especially as a woman, how uneven the impact is in terms of gender and how it shapes my ability to exercise my right to life and livelihood as a woman,"

She explains the disproportionate burden women carry.

"Women seem to bear a disproportionate share of the overall tax burden even as public spending mostly tends to favour men."

Ruth is calling for women's involvement in tax policy discussions.

"It will only take women to expose the negative impact of tax policies on their well-being.The persistence of this heavy burden on women implies that tax justice must be central to the efforts to improve women’s rights and gender equality. Our demand will not come easy. We just must keep fighting till we get what we want."

This tax injustice looks like it will only get worse

Despite the arguments and calls for tax justice and as we move through Covid and into further crises, there is likely more pressure to increase taxes on informal workers to raise revenues.

Experts argue the risks of increasing harassment, marginalisation and over-taxation of small informal businesses are heightened where governments face greater revenue pressures and place less emphasis on the equity and distributional implications of expanding the tax net.

Designing fair and effective tax policies for the informal economy

According to Michael Rogan, Associate Professor, Economics and Economic History, at Rhodes University on the Sixty-eighth session of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW68) shows in Accra, as in many other Sub-Saharan African contexts, informal workers are often willing to pay taxes if they are fair and transparent and if they receive something in exchange.

He believes that women and especially those from lowest income groups, are excluded from tax policy-making and the institutions and organisations that oversee tax systems.

To change the status quo, there needs to be a change in tax policy, and a change in who is deciding on tax.

There is the need to make sure informal and unpaid workers and their demands are fully represented and listened to in local, national, regional, and international tax discussions.

There needs to be investment in women’s rights organisations and movements working on economic justice.

Informal and unpaid workers must be involved, not just to demand that they pay less but to shape the whole tax system.

All workers, paid or unpaid, should have the power to influence global and national tax reforms, so they can be redesigned for them.

Senior Lecturer at the Department of Sociology and Social Work, John Boulard Forkuo recommends self-organisation which could be a powerful tool for advocacy for these women.

“If the traders association could be strengthened through the local government structure, they could be a strong force to negotiate for the well being of these women,”

Latest Stories

-

No student has been served unwholesome meals – Nana Boakye

53 seconds -

Galamsey has left our river deities powerless – Fetish Priest laments

15 mins -

It was unfair to destroy Leslie’s Fantasy Dome – Okraku-Mantey

19 mins -

Expired rice scandal: We won’t jeopardize people’s health or safety for any reason – FDA

24 mins -

UniMAC to host public forum on democracy and communication

43 mins -

Expired Rice Scandal: Ablakwa slams Lamens Company for “Criminal” acts

55 mins -

Avoid the use of vituperative expressions in your campaigns – NCCE

1 hour -

No petroleum revenue allotment to industrialisation in first half of 2024 – PIAC report

1 hour -

Baba Sadiq motivated me to vie for MP position – Okraku-Mantey

1 hour -

“Black Stars failure to qualify for AFCON 2025 a big blow” – Ibrahim Tanko

2 hours -

NPP’s campaign is going very well – Nana Akomea

2 hours -

Employees must file annual income tax returns – Ghana Revenue Authority

2 hours -

Does the Police law empower police to run a broadcasting service?

3 hours -

GFA dissolves Black Stars Management Committee after AFCON qualification disappointment

3 hours -

The Thomas Partey Tournament: Empowering Ghana’s Youth through football

4 hours