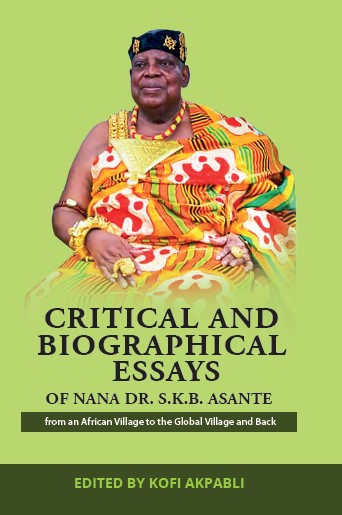

When Nana contacted me to review his biographical essays and work at this launch, I was elated with a joy that felt like having received the news of a promotion to the pinnacle of positions at my workplace. Without meaning any exaggeration nor given to speaking in hyperboles, I am justified in saying that the rarity of Nana’s standing in Ghana’s public life and his immense and unique contributions to the international civil service has meant that the enormity of the recognition accorded me by this task was not lost on me. Beyond this however, I am deeply happy, as we all should be, to be alive to witness this day---a day of testimonials and confessions (even if at the largely professional and not so personal levels). For the author has spoken about the interstices of his professional life’s experiences, summarized the tapestry of his ideas and intellectual thought, and the impressions he formed of other stalwarts, as well as those shared on his work and professional life by others.

Every now and then, one has the opportunity of peeping through the window of a great man or woman’s life through their written biographies, and beyond the learning and mentorship that comes with the discovery of their secrets and codes of success, I have quietly nurtured the penchant for learning of their human but sometimes also not so distinguished sides, such as lessons in failed love attempts, the times when they lied to their parents or children, or their low moments when they supported a football team that went into perpetual relegation such as Ho Voradep! Perhaps you may consider this shameful of me but I am sure you can forgive me for this knowing the very human dimensions of curiosity, mystery and the pleasures that come with discovering the intimate details of a great man/woman’s life. For in truth, significant mentors and achievers like Nana Asante tend to exude perfection and near excellence in public life which makes one wonder whether there are any practical and everyday downsides to their lives. In the case of giants like Nana, therefore, writing an autobiography should very much come with benefits and pains akin to that of a publicly listed company on the stock exchange. The company’s desire for public ownership comes with the pain of forced disclosures it has to make. Today, Nana’s desire to confer the benefits of his life’s work, experiences and scholarship on the current and coming generations comes with a compulsive opening up of his life in a rather invasive way. Fortunately for Nana, however (perhaps to the reader’s mild disappointment) this is a work which is largely touching on his scholarship comingled with narratives on his years growing up and professional life.

I particularly found the book a very enriching and often enchanting read. Employing a fluid and rather lucid analytical style typical of his writing, the book introduces the reader to the author’s wide diversity of knowledge and fertility of thought straddling the spectrum of subjects, themes and issues contained in his varied works. From property law, through international law to a transnational corporation and investment law, Nana’s is a rich journey of scholarship, juristic thought and concrete contribution to the world he experienced and touched. Reading through his works as digested in this book, one becomes fortified in the view that few scholars have the intellectual erudition and scholarly finesse that Nana has, and is so ably articulated in his essays.

His handling of complex polemics implicated in the themes discussed in his works reflects the calmness of spirit but also depth and strength of understanding of the subjects discussed. His mastery of topics dealt with, and the authority of his pronouncements are apt to inspire the budding scholar and impress the learned. Few, if any, can dispute the claim that of the many that Ghana has sent abroad on missions, Nana remains one of our country’s finest and most consequential exports whose work in the international community is only matched by his contributions at home. The sub-theme of the book succinctly captures the perfection of his life of humility, service and excellence- a sojourn marked by episodes of tangible and pathbreaking leadership and statesmanship! Thus, from tradition to diplomacy, our author’s life mirrors the very essence of what is good in the Ghanaian-the qualities of dedication, duty, and excellence.

The book is peculiar for its numerous revelations on facts that should inspire every reader. Even for those who may be Nana’s contemporaries like the many here today gathered, I am confident that the facts relayed will cast old knowledge in new lights and better refine perspectives on what has been known for years. In the spirit of generosity, however, I will reveal a few of these in my cryptic query “did you know”? So, did you know that Nana and the legendary Ghanaian historian & politician Prof. Albert Adu Boahen were classmates? The book reveals! Did you know that his excellency the late Bosomuru Kofi Annan never failed to return Nana’s calls through his tenure as UN Secretary General? The book says so! I am sure that with this knowledge many of us can learn lessons in humility if not courtesy from the icon of international diplomacy.

Did you know that the famed late Ephraim Amu was Nana’s teacher? This surely must be one of the few things that can truly be classified as an experience to be had once in a lifetime. I am not sure if Nana writes it in his CV. Perhaps the density of his CV would not allow that. Did you also know that law as a subject was not Nana’s originally preferred course but had to switch from reading history to law? Did you know that Nana had great lecturers including the well-known author of Street on Torts and J.C. Smith well known for his book on evidence? Did you know that Mr Jack Straw, the British foreign secretary during the infamous Iraq war of the 1990s was Nana’s student at Leeds University and once rose to his defence in a classroom situation? The book reveals this too although Nana didn’t say whether he discussed the war with him while he was foreign secretary.

Did you know that Nana provided advise on securing financing for the construction of the Kpong hydroelectric project? And did you know that Nana supervised the customary land law guru Gordon Woodman (albeit in an honorary capacity) on his PhD dissertation? I must confess that discovering this marked an inflection point for me. For the truth is, I have always deeply admired him and held him in great awe as a senior friend and mentor, but this discovery was truly humbling. For many students who passed through the ‘temporary structures’ of the faculty of law, Woodman was a god of customary law but it turned out Nana was the great teacher’s teacher of sorts. Did you know that the law faculty at Legon was originally located in the east wing of the Balme Library? And that among the pioneer students were the late Justice Dr Kludze and Hayfron Benjamin (not the former distinguished justice of the Supreme Court)? And that the structures which housed the library were nearly washed away by rains in the early years of its being built?

Nana’s book contains many instances of exciting discoveries of facts and critical legal history. I will return to giving you glimpses of what the book contains although I can only scrap the surfaces of the many more things the reader will find when reading the material. As will be apparent to any reader, this book is a gift unto cerebral hygiene and the stimulating discussions on the topics treated remain intellectually rewarding.

On the question of the organization and content, the structure of the book makes for easy reading. The overview contained in the introductory essays is as classic as it is illuminating. That chapter details Nana’s journey to becoming a lawyer, an academic and an international civil servant. The author uses the opening lines of the book to also state his intellectual worldview and subterranean musings on the challenges that confronted and continue to beset law as tool of third-world development. The author poignantly notes on page 7 of the book,

…my experience of observing the political culture of multi-party politics in Ghana and several developing countries has persuaded me that exclusive governance and extreme majoritarianism which prevent an inclusive and consensual approach to national development are detrimental to nation building and sustainable development. This phenomenon…is most inappropriate for plural societies such as ours, where political alignments are marked by sectarian, regional, ethnic and religious factors”

Any passive observer will readily concede that Ghana’s politics suffers from dysfunction and to take the lead founding father saying it should certainly reverberate and get all pausing for some introspection. Nana’s reflections in this chapter led him to draw our attention to the peculiar factors that inspired the “Asian Tigers” to rise to economic glory. Among the 6 listed factors, Nana reminded us of those countries’ preference for meritocracy and given the preeminence of favoritism, nepotism, tribalism, and other preferences promoted by corruption and other inducements, this advice should hit home in a rather instructive way to the average reader of the book. His emphasis on the need for integrity in public life especially within the context of international negotiations is notable. At page 10 of the book, our author forcefully argues that “

[D]evelopment projects may be permanently flawed, national revenues may be scuttled, a country’s balance of payment plans may be aborted, and indeed a government may be overthrown and political instability unleashed in consequence of scandalous and lopsided agreements inimical to the national interest.

Need I say more?

His critique of the time-honored international law principle of pacta sunt servanda is apt. Drawing on the inequities in transactions and negotiating power involving African chiefs and TNCs and the general political economy surrounding colonial possessions and traditional actors in these colonial states, Nana argued that these justified a nuanced usage of this concept and for that matter the liability of post-colonial states and people. Nana’s eloquent statement of position on these controversial subjects has been well received in the legal academy globally and critical plaudits given by scholars like Atuguba, Magraw, Tsikata & Kuuya testify to the wide consensus enjoyed by his views and perspectives on the role law plays in development and his concrete contributions to the cause. His intense scholarship and advisory opinions while working with the UNCTC helped shape a body of juristic thinking on international law as it relates to TNCs and the predatory relationship that had existed between these global megaliths and African governments and actors. His realist view of things is aptly captured in Tsatsu Tsikata’s words when he asserted that

His has not been a commitment to law as a static, formalist construct, but rather a commitment fundamentally, to the value of law and the legal learning for the wellbeing and progress of humanity, especially for addressing the challenges of the developing world. This has been the hallmark of his truly distinguished career at home and abroad.

Nana’s experience with handling the Kashmir issue during a student debate at Leeds is both apt to make one laugh and feel the chill of an African professor thrust in the midst of a boiling and endless geopolitical crisis in Asia. His own sense of humor in retelling the story and his early lessons of learning to listen to the premonitions and gut advise of his wife remains starkly instructive for the uninitiated of our time. The mixed emotions I experienced reading that part of the book also led me to the lessons of religion, geopolitics and scholarly enlightenment and how Nana’s faith in the power of wit and neutral or objective academic facts articulated in debates were dashed with the triumph of emotions and entrenched nationalist sentiments on the day.

His contribution to legal education in Ghana is adequately stated in the book and the fact that he was one of five foundation lecturers of the faculty of law at the university of Ghana remains a golden tribute to his role and place in the pantheon of legal scholars and scholarship in Ghana. The sheer galaxy of lawyers and legal academics who formed the early crop of students to have passed through his hands should sound dazzling to the ears of any listener with relevant knowledge. The shortlist without their titles, include, Kludze, Hayfron-Benjamin, Ken Yeboah, Akuoko Sarpong, Amoono Money, Sam Badoo, Ofori Amankwaah, Sekyi Hughes, Date-Bah, Fiadjoe, Kwami Tetteh, Brobbey, Bimpong Buta, Modibo Ocran, and Atta Mills. His leadership of the faculty of law in part resulted in the recruitment of well-known faculty members and Deans like Ekow Daniels, Ofosu-Amaah, and J.K. Agyemang. Our author’s reflections on the deportation of a dozen members of the faculty of law under the Nkrumah regime shows a man deeply affected by the development of an era he called “turbulent” and “difficult years”. While Nana did not state in explicit terms the effect of these developments on the academic philosophy and fortunes of the faculty down the years, I am tempted to hazard a guess, namely that the lasting legacy of this development outlived that era and continues till this day in the legal academy.

Consistent with his reflections on nagging questions of education, scholarship, and academia, I found Nana’s critique of academic formalism and our ultra-dependence on western scholarly sources in his book mostly heartwarming. His recognition of the flaws in a unilineal conception of development under which Africa’s progress has been inextricably tied to the westernization of its ways and institutions can hardly be overemphasized. Relying on scholars such as Yankah whose disenchantment with the uncritical preference for western sources over and above those of Ghanaian and African sources, Nana reiterates an old problem. As a younger academic, I have always found this enduring reality troubling and frustrating since it forces the scholar to forcibly disown his own local knowledge as he seeks solutions to challenges of his environment. The resulting contradiction could be part of the reason African scholarship only rests on book and file shelves once completed but hardly impacts the world for which the researches were undertaken.

And even when we find our own worthy of citation, we treat it as if it they are materials vouchsafed us having been deemed worthy merely because they appeared in western journals. If academia is to lead changes in society, then why do we reflect the often the dead or dying learning of others. In any case why must we necessarily cite others even when our own is not lacking. For the truth is that pathbreaking scholarship often have prior works of others to benefit from and in these steads, the works of others when cited are often so done to address our minds to the paucity or dearth of works of the nature embarked upon. Ghanaian universities have downplayed their own journals in favor of western ones and the expression “peer reviewed” journals have come to symbolize, in reality, western journals. Capped with the condescending treatment by western journals of third world scholarship in general, this has resulted in the untenable situation in which African and Ghanaian scholarship has generally suffered compared with others.

His terse but loaded question whether Ephraim Amu would have been elected a fellow of the Ghana Academy of Arts & Sciences before the inauguration of his memorial lecture in his honor reminds us of how as a people, we have become obsessed with form over substance. With impressions over content. Nana’s praise of Dr Amu is a fitting eulogy to a man whose work has, in many ways, come to define our musical identity as a country. Dare I say that with Nana’s instructive reminder, we have many Ephraim Amus walking the streets of Ghana who will never be acknowledged nor honored because they do not respond to the formal accolades of Ghanaian excellence. Nana’s advise is a timely reminder to us for a rethink and about turn and an about turn on our standards of assessment and acknowledgment of merit.

I crave your indulgence for a few more teases on historical facts. These teases are compelling quizzes that should justify your buying and reading Nana’s critical and biographical essays. Did you know that the word Dondology was actually invented by a student of the University of Ghana who wrote a letter to the vice chancellor protesting the presence of the dondo onto the serene and to borrow Nana’s description, ‘rarified’ university of Ghana campus, and complained of its lowering the standards of the university. Prof. Nketia loved the word and rather championed it abroad. Perhaps if all student protests in the past have been lettered and less militant in their protestations, our diction would have been richer for it. And did you know that Nana was responsible for drafting the memo that coined the famous or infamous (depending on where one stood on the ideological isle of those days) “Yentua” word that literally became the rallying cry for Ghana during the debt crisis of the 1970s? In the rather dismal experiences of our country in those moments of the decade, Nana pins our woeful performances resulting in the distress to a regime of poor handling of international transactions.

In his paper, “The Challenge of Our Legal Heritage” presented before the Lagos Faculty of Law in 1975 [the year I was born], Nana urged the integration of African customary law into the mainstream legal system. Having superintended the writing of the 1992 Constitution, a clear effort was made in that direction. So, what does Nana think of the courts’ application of customary law today? Does he think that the subsidiary character of customary law promoted during the colonial era symbolized in cases like Angu v. Atta has been corrected by the introduction of article 11 and the making of customary law a source of law? I urge you to read his book and form your impressions of his strong perspectives. But perhaps even more tellingly, Nana reveals that the Transitional Provisions of the Constitution did not form a part of the work of the Committee of Experts but were included after the conclusion of its work. This piece of information did not appear under one of our teases “did you know” questions given the controversies surrounding those provisions, and the fact that the issue will not be resolved even with the most lucid clarifications made on them. For that therefore, the question remains open, the “horse’s” own words of clarity notwithstanding.

On the controversial issue of the scope of presidential powers and whether they were excessive or proportionate to the functions of the president contemplated under the Constitution, Nana exhibited the comportment of the true and exemplary academic that he is when he recanted his earlier position that the powers of the president were not excessive. It is apparent from the totality of his writings on this and my own personal engagement with him on the subject that the evolution of his thoughts might have been informed by the realities of executive behavior over time. It would seem from the historical record that the committee of experts did not necessarily favor the outcome arrived at in the current Constitution but recommended a system with diffused powers for the president and other executive authority. The preference for a strong executive may seem to be the position of the consultative assembly and Nana’s current support for what I think is the dominant position solidifies the view of many and should hopefully drive the agenda for a nuanced constitutional change. I couldn’t agree more with his view that in a rather bizarre way, this difficulty was further worsened by the Presidential Transition Act of 2012 which introduced discontinuity in governance like never before seen in Ghana while counterintuitively augmenting the appointing power and patronages of the incoming president. In a similar vein, I share his views on the relative obscurity of the Council of State in the governance dynamics in the country, and the flaws of insisting that a majority of Ministers of state came from Parliament although he stopped short of prescribing what needs to be done in respect of the former. Coupled with the rather dysfunctional use of the procedure of “certificate of emergency”, Nana argues that the review and audit competencies of Parliament is often undermined in cases in which the institution is called upon to approve major transactions involving the government of Ghana and third parties. Our author’s sentiments copiously vindicates the popular opinion that the use of that procedure represents an abuse of process and a blatant means of reducing the accountability functions of Parliament to a perfunctory process.

Nana also touched on the vexed issue of the constitutionality of private members sponsoring or initiating bills, and rejects the long standing restrictive and self-limiting interpretation put on the provision by Parliament. Having been frustrated by the unnecessary limitation Parliament has placed on itself for sometime now, I was pleasantly impressed when former speaker Rt. Hon Mike Ocquaye at a parliamentary induction training at Koforidua hinted that he was going to encourage private members to sponsor legislation as he disagreed with that reading of article 108. It is refreshing that our author himself being the lead expert who drafted the Constitution shares that view. Today, I am advised that that lethargic record has been broken and private members’ bills have either been passed or are pending before the house. I happily considered the issue moot.

Nana’s book also touches on the question of access to the Supreme Court and the seeming inundation of the Court with many cases. The issue turns on the combined jurisdiction of the Court, namely the appellate and original jurisdictions of the Supreme Court and the issue of standing or capacity before the top court. Our author expresses regret at the inundation of the apex Court by cases some of which should not ordinarily have ended up at the top court. He confesses his preference for a more restrictive access which would allow the Court to deal with core and fundamental issues of constitutionality and standing. Analyzing his position, it becomes evident that Nana is clearly not impressed with the trade-off achieved in the end under which the preference for jurisdictional equity has trumped the ends of speedy and efficient justice. His prescription for constitutional amendment to restrict access is one I sympathize with, except to add that I was hoping (perhaps unjustifiably so) that our venerable author would have echoed a position I have held, namely the fact that the problem could be resolved by the creation of a specialized constitutional chamber out of the Court with a mandate to only hear and determine constitutional cases. Thus, while the American model cited by Nana has worked rather well for the United States, the standard approach globally and certainly the dominant model in continental Europe has been the operation of constitutional courts whose specialty in determining constitutional cases make them both suitable and concentrated in the task of interpreting constitutional cases without the distraction of daily appellate matters. I am convinced that when so adopted, this will solve Nana’s worries on heightening the standards of accessing the Court’s jurisdiction including refining the boundaries of standing and cause of action classification.

Reflecting his diversity of perspective on the thorny issues of governance, Nana’s work contributed to the ongoing debate on local governance and the introduction of the elective principle in the framework designed. Having obviously articulated his position in the extant provisions of the Constitution, Nana was coy in his position on the raging debate on whether or not to elect our MMDCEs while passively admitting a potential advantage of electing these officers of state. He argues that “ [O]ne conceivable merit of the admission of party politics in local government is that it would be conducive to the concept of inclusive government if elected DCEs and the President of the Republic belonged to different political parties”

Needless to say that Nana’s argument draws attention to the drawbacks of the winner-takes-all menace currently obtaining under the 1992 Constitution with the appointing powers of the President used to promote the politics of patronage and alignment, the prospect of having different parties electing different officers for president and MMDCEs begs the question if electing MMDCEs may not split the unitary executive mandate created under article 57. Nana leaves the question untouched and perhaps his reticence in developing an argument and stating a conclusive position may be due to a desire to allow the raging debate to continue and evolve independent of his influence.

Beyond the impressive volume and depth of scholarship contained in the book, this work is a resume in praise of the life, work and achievements of other stalwarts and compatriots of Nana. His description of his experiences with the towering J.B. Da Rocha illustrates Nana’s humbling acknowledgment of Mr. Da Rocha’s eminence and learning as well as his mentorship of him when they both returned to Ghana following the conclusion of their studies in Nottingham. His ready acknowledgment of the intellectual standing and weight of his “ African heroes” (and the list is impressive) like Mr. Seth Amoako Owusu, the late Prof. Yaw Benneh, Judge Thomas Aboagye Mensah, Dr. James Nti, Dr Kwaku Addeah, Justice VCRAC Crabbe, Prof. Nketiah, Prof. Kwame Gyekye, James Nii Tettey Chinery Hesse, Dr Seth Bimpong Buta, among a host of other distinguished notable academics and personalities, speaks deeply to a man conscious of the academic community to which he belongs and in which his own stellar achievements in academia and international service is reflected in the company he kept. Having been taught by at least two of these personalities - Prof. Benneh, & Prof. Gyeke, I have personal knowledge of Nana’s heroes I am convinced that Nana extols the virtues of these people with pristine truth and admirable candor. My student-oriented admiration of the two academics who taught me besides their scholarship and felicities in teaching and delivery, has been fortified by Nana’s overall endorsement of them as some of the finest brains Nana had encountered to have come from Africa. Mr. Yaw Benneh was particularly known to me and was my academic godfather having received me into the faculty of law at Legon as his teaching assistant in 2002. Like many others I believe, I share Nana’s utter shock and grief in his tragic demise the kind words uttered by our author in his honor is a fitting eulogy before his peers.

Even more poignantly, our author testifies of H.E. Kofi Annan’s work like few have done. Bringing to the fore H.E. Annan’s achievements like the UN Global Compact and the warm humility in personal friendship with him should endear an already loved man to a world moving on from the legacy. As I read through the book, I sweated in search of things I could disagree with, to - at least- convince myself that I was doing some thinking in my review as is done in standard reviews of this kind. Sadly for me, I failed. For so deeply thought through are his positions that as I read through the book, I found myself inevitably agreeing with nearly all his arguments, and as was often the case, his lamentations on Africa’s failures.

True biographies contain balanced stories of joy and pain! Of triumphs and failures, and sometimes of glories and adversities. Knowing this however, did not stop me from thinking that my secret pleasure of zeroing in on the juicy part of such biographies as Nana’s was going to be disappointed-at least from the standpoint of his professional developments. For the truth is personalities like Nana often exude such level of excellence that it becomes hard to picture any circumstances of failure in their lives. It therefore came to me as something of a shock when I read in the book that Nana had experienced three failed attempts at getting onto the International Court of Justice. I have been at pains to reflect on this because for a man the standing, gravitas, eminence and quality of Nana, I say it without equivocation or exaggeration that it is truly a loss to the ICJ that he was not facilitated onto the court in his triple attempt. The gaping testament of his works at the UNCTC, his scholarship in international law and transnational corporation, and the experience and learning he brings would have really enriched the jurisprudence of that court. His microcosmic background as a village boy and blended sophistication spanning public services in Ghana, international civil service and lead constitutional reform consultant uniquely positions him like no other as a judge of the ICJ. Perhaps the ICJ’s loss was Ghana’s gain and Nana’s dedication to the cause of this country is staring us all in the face.

Given the volume and relevance in detail of Nana’s book, I have an impossible task of summarizing this up in a review exercise within the time given. In content, this book provides an enchanting and compelling material for anyone with the slightest interest in law, international diplomacy, chieftaincy, politics and governance, and public policy. Its fluid style makes reading easy and assuages any boredom in dry texts or discouragements occasioned by the density of size. The structure of the material is coherent and should endear itself to any reader with a penchant for organization and flow. Nana’s wit and excellent combination of humor and tampered occasional self-deprecation should get even the most serious reader laughing now and then, and this is apt to create the needed intimacy and bonding between reader and author as you make your way through the pages. For the avid reader will find some of the discoverable facts relayed here somewhat disconcerting given the revelation of intricate details about the political history and evolution of our country and how specific episodes of things panned out. For me, it was precisely that curiosity, that hunger of seeing the end of it that spurred me on.

This book is an exhilarating read and tried as I did, I have barely scrapped the surface in what I have shared. The devil is still buried in those details and at this stage, I will say with little shame, that I have had the pleasure to pre-discover ahead of you. For many are the books you have read---you will read, but there will be none like this book. Do you know why? For if I speak with surprising equanimity on this, it is because I know that there will not be a biographical and critical essays piece to be authored by the lead author/consultant of the 1992 Constitution, a veritable international statesman par excellence, a chief of reputable eminence, a towering academic, and certainly a village boy with a story for the ages!

I would like to profusely thank Nana for the honor and opportunity to review his work. For those who stand in the moment of history often have the significance of the time lost on them and history is left to posterity to appreciate. I do not have the moment lost on me and I am grateful that I have witnessed this day and participated in it. And so, I leave you with the inspiring guide of the bible, that we think of the things that are noble; that we embrace efforts that are worthy of praise; and that communicate things that are of good report. For Nana’s life’s enterprises certainly befit these and the chronicling of his life in this book shows that of the things of excellence, he attempted and prevailed and it is on those that I invite you to think, applaud, and be inspired!

Thank you.

Latest Stories

-

Baltasar Coin becomes first Ghanaian meme coin to hit DEX Screener at $100K market cap

12 minutes -

EC blames re-collation of disputed results on widespread lawlessness by party supporters

27 minutes -

Top 20 Ghanaian songs released in 2024

48 minutes -

Beating Messi’s Inter Miami to MLS Cup feels amazing – Joseph Paintsil

1 hour -

NDC administration will reverse all ‘last-minute’ gov’t employee promotions – Asiedu Nketiah

1 hour -

Kudus sights ‘authority and kingship’ for elephant stool celebration

1 hour -

We’ll embrace cutting-edge technologies to address emerging healthcare needs – Prof. Antwi-Kusi

2 hours -

Nana Aba Anamoah, Cwesi Oteng special guests for Philip Nai and Friends’ charity event

2 hours -

Environmental protection officers receive training on how to tackle climate change

2 hours -

CLOGSAG vows to resist partisan appointments in Civil, Local Government Service

3 hours -

Peasant Farmers Association welcomes Mahama’s move to rename Agric Ministry

3 hours -

NDC grateful to chiefs, people of Bono Region -Asiedu Nketia

3 hours -

Ban on smoking in public: FDA engages food service establishments on compliance

3 hours -

Mahama’s administration to consider opening Ghana’s Mission in Budapest

3 hours -

GEPA commits to building robust systems that empower MSMEs

3 hours