After the bullet burst through his mouth and neck, Cesar Kimbirima lay in the long grass, thought of his family, and waited to die.

He had been shot before, of course. Three times in fact - leg, leg, and arm. But this was the worst.

And so, as the sky started spinning, and his consciousness faded to black, he thought it was over. His life would end in the long grass, while his blood poured into the dry Angolan earth.

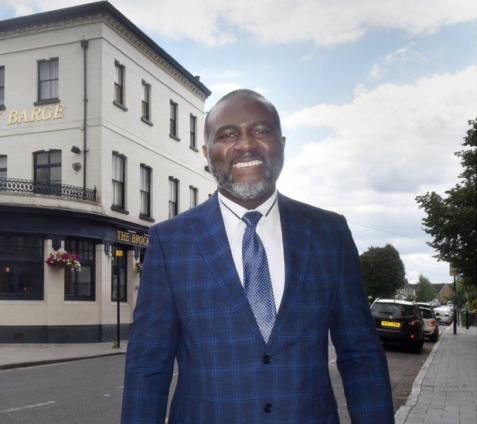

More than 20 years later, that dying soldier pours pints at the pub he manages in south London. As he chats to punters, and waves to babies in prams, there is no hint of Cesar Kimbirima's former life.

No hint, that is, unless you look closely at his neck. Because there, just above his collar, is the scar: a reminder of the bullet, the coma, and the escape.

Cesar Kimbirima was born in Angola in south-west Africa, and grew up one of 11 siblings. His mother was a primary school teacher; his father was a nurse and electrician.

His family lived in Huambo, the third biggest city, and elsewhere in the country. And, despite the long-running civil war, he enjoyed school and was a happy child. But in 1990, when Cesar was 17, his childhood ended.

"The army got me in the street," he says. "That's the way it used to be. If you were big, tall, they just grabbed you and made you join. Without your father's consent, without anything."

He was not allowed to pack a bag. He was not allowed to say goodbye to his family - whom he then didn't see for three years. But none of it was a surprise.

"As a kid back then, we always used to say 'If they get me, that's it'. Because we knew it was going on. So when you get caught, you have no choice."

Could he run? "If you try, you might get killed. So you'd better stay there, sit down on the floor, and wait for the truck."

The Angolan army did not - or could not - care for its soldiers. During six months' training, the conscripts would get one meal a day. After training, when they were sent on missions, they might get two packets of biscuits, one can of condensed milk, and a water container.

Those rations were supposed to last 30 days.

"We learned how to survive," Cesar remembers. "If you get a plastic bag, wrap it round the leaves, and seal the end, the tree will sweat. And when it starts dripping, that's water."

He was shot for the first time aged 18. "In the leg," he says. "We used to camp [to protect villages in the civil war]. Left-wing forces came down and attacked us. We were kids, we had no experience."

Cesar was shot twice more, in separate incidents, before the attack that nearly killed him.

"Normally they [the opposition forces] came in the middle of the night," he says. "This time, they came around 8pm. We heard a noise. One of my colleagues started to run, so they started shooting. So we shot back. And then I felt really cold."

Although he didn't realise at first, he had been shot through the mouth. He ditched his gun - knowing he would be killed if the enemy found him with it - and kept running. After 15 or 20 metres, he lay down in the grass and felt the blood pour down his back.

"I thought about my family - that I didn't get to say goodbye," he says. "I thought, that's it - my life has ended. That's it - another young guy is gone. That was my thinking. That's the last thing I remember."

Cesar woke up in a hospital - "I didn't believe I was alive" - and was treated for two or three days. But then he went into a coma, where he stayed for five months. When he woke up, the doctor told him he wouldn't walk again.

There was some good news. After nine years in the army, he was discharged - they did not want a soldier who could not walk. But there was bad news, too. He was 26, with no money, and no idea how to find his family - which by now included the mother of his child and their three-year-old daughter. He left the hospital with nothing but a pair of wooden crutches.

"It was a survival situation," he says. "I was begging for food and money, and somewhere to stay."

Eventually, he met soldiers from the United Nations. "I think they were Americans - they were talking English," he says. "They knew all the young kids in that situation. They knew I was wounded. They questioned me, found out what happened."

The Americans found him accommodation at a centre for injured soldiers: "A hundred people, big injuries, people with no legs." After tracing his family, he told them he planned to leave Angola.

"Mentally, I could not stay," he says. "Whatever you say against them [the government], they will get you."

And that is when the Americans saved him again. "They said, you know what, we're going to help you leave the country," he says. "They organised everything - I didn't spend any money."

He doesn't know the details - or whether it was an official scheme. He didn't even know where he was going - Africa, Europe, or elsewhere. But it didn't matter. Six months after leaving hospital, he was leaving Angola and its civil war. Even now, Cesar remembers the words of the American who helped him.

"Now I understand what he used to say," Cesar says. "He said 'Young lives cannot be wasted like this.'"

As it turned out, Cesar, his partner, and his young daughter were given flights to the UK, via Lubango in Angola, and Kenya. They were safe. But as they began their journey to England, three major problems remained.

They had no money. They spoke no English. And they didn't know a soul.

After arriving in the UK, the young family - now refugees - were taken to the asylum processing centre in Croydon, south London. They were sent to hotels and hostels before Croydon Council arranged somewhere to live.

Cesar could still not speak English - "I used to carry a little dictionary in my pocket," he says - and so began a basic English course at Ambassador House in Thornton Heath. From there, he did another English course at Croydon College, before starting catering qualifications.

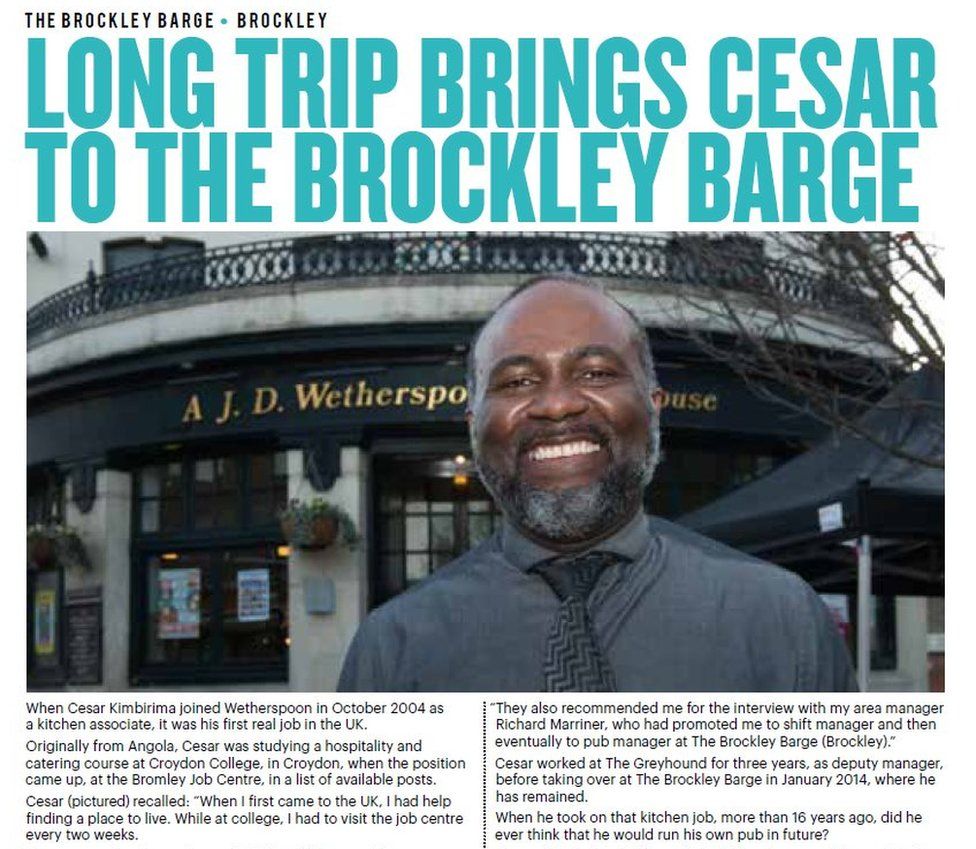

He wanted a job - "I can't be depending on government, I don't work that way" - and, via the job centre, learned of vacancies at the Richmal Crompton pub, part of the Wetherspoons chain, in nearby Bromley. But it's fair to say he wasn't familiar with the chain's cheap-and-cheerful culinary style.

"I had taken my chef's set in a case - knives and so on," Cesar says. "The woman who interviewed me said: 'What's that?' I told her it was my chef's set and she started laughing. I didn't understand why.

"She took me into the kitchen and said - 'Look, that's our kitchen'. It was a microwave, a fryer. At first I was shocked! But then I thought - I am fine, I will do it."

He was not a permanent UK resident, and so needed dispensation from the Home Office. But in January 2004, he started working in the Wetherspoons kitchen - his knife set left at home. "I felt really welcome," he says. "Nice pub, nice atmosphere, nice company."

Three years later he moved to the front of the house, climbed the ladder, and in January 2014 became manager of the Brockley Barge Wetherspoons. His 17-year-old son, Joe, also works at the pub (when not at college), as did his 23-year-old daughter, Duanie. She, incidentally, has just graduated in politics from Aberystwyth University.

At the end of 2020, Wetherspoons boss Tim Martin visited the pub and was so impressed with Cesar's story, he asked the firm's in-pub magazine to feature him. For the first time, the Barge customers realised the life story of the man behind the bar. Some people even came from other pubs to pay their respects.

"I had people who had never been this way," he says. "They saw the magazine, they just wanted to say congratulations, knowing where I came from."

Since arriving in the UK, Cesar has been back to Angola once, in 2014, to get documents. "It was one of the scariest things I've been through," he says. "The flight was fine, but the airport was scary - soldiers everywhere, guns everywhere. When I boarded the plane to come back, I was so relieved."

His future, then, is in the UK - and he intends to keep working hard at Wetherspoons for his family and four children, the youngest of whom is four.

"When you're a kid, if you have a very good life, you probably don't feel it," he says. "But if you didn't have a good life - or if something happens, like when I was forced into the army - you know about it. I don't want to see my kids face the same issues. I want to do something better for them."

And with that, the manager of the Brockley Barge leaves his office, walks down the stairs, and gets back to the pub: chatting to punters; waving at babies; the scar on his neck only just visible.

Latest Stories

-

Fugitive Zambian MP arrested in Zimbabwe – minister

20 mins -

Town council in Canada at standstill over refusal to take King’s oath

31 mins -

Trump picks Pam Bondi as attorney general after Matt Gaetz withdraws

43 mins -

Providing quality seeds to farmers is first step towards achieving food security in Ghana

54 mins -

Kenya’s president cancels major deals with Adani Group

2 hours -

COP29: Africa urged to invest in youth to lead fight against climate change

2 hours -

How Kenya’s evangelical president has fallen out with churches

2 hours -

‘Restoring forests or ravaging Ghana’s green heritage?’ – Coalition questions Akufo-Addo’s COP 29 claims

2 hours -

Ensuring peaceful elections: A call for justice and fairness in Ghana

3 hours -

Inside South Africa’s ‘ruthless’ gang-controlled gold mines

4 hours -

Give direct access to Global Health Fund – Civil Society calls allocations

4 hours -

Trudeau plays Santa with seasonal tax break

4 hours -

Prince Harry jokes in tattoo sketch for Invictus

4 hours -

Akufo-Addo commissions 200MW plant to boost economic growth

5 hours -

Smallholder farmers to make use of Ghana Commodity Exchange

5 hours