Kristal Hansley grew up surrounded by community. After school and in between piano lessons, Hansley would tag along with her grandmother, Avellar, to all types of neighborhood meetings in Bushwick, New York, where they lived.

“I hated it at first,” says Hansley, 31, “but then it was already entrenched in my life.”

Avellar was a local icon. She founded a community garden that was eventually named after her. Here, neighbors would gather regularly to share meals and music.

Hansley didn’t know it then, but her grandma was planting a special seed within her: a love for community, and a love for the earth. Avellar looked to the soil and the plants. Decades later, Kristal is looking up to the sun.

She’s the CEO of WeSolar, a community solar company providing affordable energy to low- and moderate-income families.

Hansley says she became the first Black woman to launch a solar company when she founded WeSolar, already leaving her mark on an industry that is notoriously dominated by white people or, well, white men.

Among senior executives, 88% are white and 80% are men, according to the 2019 U.S. Solar Industry Diversity Study.

Hansley didn’t let that hold her back. In fact, she’s celebrating her Blackness through WeSolar. Just look at when she launched it: Juneteenth, a holiday marking the end of slavery in the U.S. “I was sending a message out the gate for the equity,” Hansley says. She didn’t let the pandemic slow her down, either; her community was in need.

In Maryland, customers owe about $300 million in unpaid gas and electric bills. Black households across the U.S. pay more for their energy than white households, according to a June 2020 working paper.

WeSolar promises to reduce its low- to moderate-income customers’ bills by at least 25%. The company also skips fees and allows customers to cancel without penalty.

On average, their customers stand to save about $300 a year by going solar.

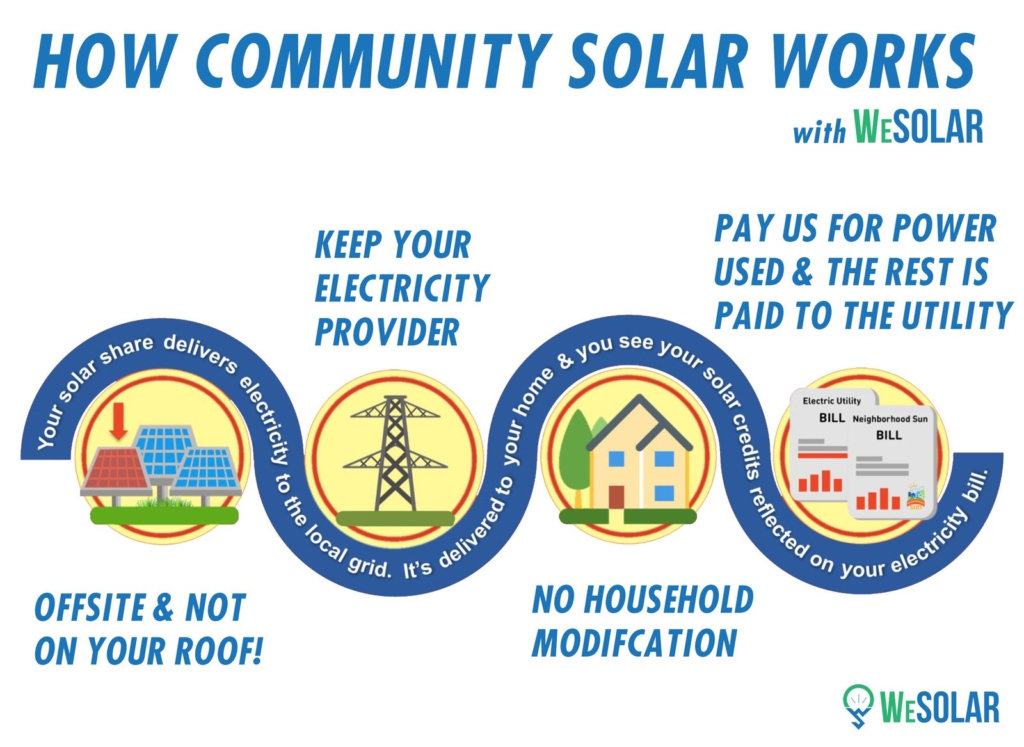

That’s its power: Community solar can be more accessible than the rooftop solar many people know. Instead of purchasing the panels themselves to install on a roof, customers can purchase or lease panels that sit on a solar farm nearby.

These panels send energy back into the greater grid, which powers customers’ homes.

They receive credits on their energy bills as a result. This breaks down the barriers many residents face to accessing renewable energy, especially those who rent or whose roofs can’t support this technology.

But another key barrier is trust, says Tony Reames, an assistant professor of environmental justice at the University of Michigan, where he researched solar adoption among low- to moderate-income households as part of his project with the National Renewable Energy Lab.

“Having diverse companies or companies owned by people of color, managed by people of color, coming into communities of color, I think that’s totally important,” he says. “Those kinds of social elements...social barriers, social connection, trust, all of those things were still very significant in whether someone received information about solar and actually adopted or not.”

Trust is at the heart of Hansley’s work. She believes a lack of trust is why the solar industry struggles to attract low- to moderate-income customers.

As a Black woman from the neighborhood, her customers may trust her just a bit more than a random white dude knocking at their door. After all, Hansley is a community organizer first.

She got into the solar game after working on Capitol Hill as a lobbyist for about five years.

She learned the ins and outs of policy implementation, and then, how that translates into changes in the community. In 2019, Maryland passed a bill to transition the state to 100% clean energy by 2040.

As part of this work, the state also formalized a program to provide grants and funding for community solar. Hansley saw an opening.

She first worked for another company, Neighborhood Sun, where she led its low- to moderate-income program.

Her job was to get people within this income bracket signed up with the company’s solar farms.

She spent time on the ground, knocking on doors, giving weekly presentations at local meetings—all to build relationships, to build trust. As she put it, she became known as “the solar woman.”

That’s how Tamara Toles O’Laughlin, the North America director for clean energy advocacy group 350.org, met Hansley.

At the time, O’Laughlin was leading the Maryland Environmental Health Network. She walked into a meeting of elderly Black women and saw Hansley talking to them about solar energy.

Seeing Hansley’s energy and ability to connect firsthand instilled a sense of solidarity for O’Laughlin, who is also a Black woman in a predominantly white space.

She recognized the value of this work in reducing greenhouse gases: The average U.S. household emits anywhere from 0.4 to 10.8 metric tons of carbon dioxide in energy use a year, according to a study published earlier this year. All that is offset when switching to renewables.

Eventually, Hansley left Neighborhood Sun to contract for them under her own company: WeSolar. That move is something O’Laughlin commends wholeheartedly.

“She did a fantastic job in helping people realize that [solar] is not something that is for other people,” O’Laughlin says.

“When I found out she was going to be starting her own organization where she does this for her people as one of her people, I wanted to be supportive of her.”

She wasn’t the only one who wanted to support. Erica Ruffin, 37, remembers seeing Hansley share the launch of WeSolar on Facebook. Ruffin knew Hansley from their Howard University days.

When she saw Hansley was selling clean energy, she reached out. Ruffin signed up her house in Lanham, Maryland, a predominantly Black community, at the end of July.

She’s still waiting for the solar farm to have enough subscribers to begin sending power through—WeSolar estimates Ruffin will receive her credits by December—but she doesn’t mind.

Ruffin feels empowered knowing she’s not only supporting solar—her personal contribution to fighting the climate crisis—but also a business owned by a Black woman.

“We have to have power,” Ruffin says. “Why not do it and save the planet at the same time, and support a minority- and woman-owned business?”

Of course, Hansley is not your ordinary CEO. She didn’t come from a history of generational wealth. Her family hadn’t already created a solar empire for her to inherit.

She did this on her own. (Well, perhaps her grandma helped a little when she passed on that passion so many moons ago.) Now, Hansley is channeling her own energy back into the Black community, which the fossil fuel industry has long exploited through pollution and deceit.

Maryland is only the beginning—WeSolar plans to soon expand to cities around the country. As she forges ahead, the people who surround her know that Hansley has it handled.

Ruffin was quick to say it best: “She was literally born for this.”

Latest Stories

-

4-year-old cured leper walks again after Bawumia sponsored her special surgery

18 minutes -

Dorcas Affo-Toffey, earns dual Master’s Degrees in Energy, Sustainable Management, and Business Administration

36 minutes -

T-bills auction: Government got GH¢21.5bn in November 2024, lower than target

4 hours -

Ghana to return to single digit inflation in quarter one 2026

4 hours -

Panama’s president calls Trump’s Chinese canal claim ‘nonsense’

5 hours -

Manmohan Singh, Indian ex-PM and architect of economic reform, dies at 92

5 hours -

Government is not been fair to WAEC – Clement Apaak on delay to release WASSCE results

5 hours -

Bayer Leverkusen’s Jeremie Frimpong donates to Osu Children’s Home in Ghana

8 hours -

GPL 2024/25: Heart of Lions beat Young Apostles to go three points clear

8 hours -

Dance battles, musical chairs light up Joy FM Party in the Park

9 hours -

Kwabena Kwabena, Camidoh, Kwan Pa Band, others rock Joy FM Family Party in the Park

9 hours -

GPL 2024/2025: Aduana beat struggling Legon Cities

9 hours -

GPL 2024/25: Bechem United fail to honor match against Holy Stars

9 hours -

Cooking competition takes centrestage at Joy FM Family Party In The Park

10 hours -

Album review: ‘Wonder’ by Nana Fredua-Agyeman Jnr

12 hours