Most countries all over the world have been under some form of lockdown restrictions since January 2020 to contain the spread of the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic.

This followed the first reported case of the virus in December 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of China’s Hubei province. Almost 17.6 million people have so far been infected with Covid-19, with over 680,000 deaths reported worldwide and close to 11.2 million recoveries as of 31 July 2020, according to Johns Hopkins University data.

Ghana recorded its first confirmed case on 12 March 2020. Since then, there have been 37,812 total confirmed cases with 34,313 recoveries and 191 deaths as of 31 July, according to Ghana Health Service data.[2]

In response to the outbreak, the Ghanaian government, like other nations, very early in the pandemic in mid-March temporarily closed land, air and sea borders since to contain the spread of the virus.

Additionally, universities, high schools and primary schools were closed with movement restrictions imposed as well as a ban on church activities, funerals, and other public gatherings.

The government, however, begun removing gradually some of these lockdown restrictions from 20 April when it restored the movement of persons within some parts of the Greater Accra and Greater Kumasi metropolis.

Additional relaxation measures taken since then include lifting the ban on worship and allowing senior high school students back to their schools to write their exams, among others.

Nonetheless, the removal of some of these measures has not been without controversy as several civic organisations, and other groups, raised concerns about the early removal of some containment measures, more so given limited public education.

There were also concerns that the virus could be spreading into the more densely populated (and lower-income) parts of key contagion cities such as Accra and Kumasi which has the potential to spread the virus further.

The purpose of this article is to chronicle the evolution of COVID-19 in Ghana by undertaking an analysis of the case data, the social response to the crisis and health sector impact.

We also highlight the potential prevented COVID-19 cases if Ghana implements early diagnosis, isolation and treatment of infected persons.

2. Ghana’s case data trends

2.1 COVID-19 case trends

Ghana recorded its first two cases of COVID-19 cases on 12 March 2020. On 28 March when Ghana had recorded 141 confirmed cases, the President imposed a partial lockdown of Greater Accra and the Greater Kumasi Metropolitan Areas which commenced on the 30 March (Figures 1 & 2). On that day, the country’s cumulative case count was 152.

When the restrictions were lifted on the 19 April, Ghana’s cumulative case count was 1,042. This meant that 85% (892) of confirmed cases had occurred when the limited restrictions were in place.

Over the partial lockdown period also the doubling rate of infections in the country was 7-days.

The week following the lifting of restrictions saw a slight slowing down of contagion with the doubling rate increasing to 9-days and the country recording a cumulative case count of 2,074 by the 28 April. By this time, it was also evident that community spread was becoming a concern.

Of the total number of cases, 82% (1,700) had no established travel history. Also, though the average overall sampling positivity rate was 1.83%, samples collected through routine surveillance (that is, those with no history of contact with a previously infected person) had a positive test percentage of 2.71%.

It took a further 9-days for this number to approximately double to a cumulative count of 4,012 on 7 May. A further indication that the limited restrictions had altered the trajectory of the pandemic curve slightly. By 30 May, when the cumulative case count was 8,070, the doubling rate was now 23-days.

June saw a further addition of 11,091 new cases (a daily reported case average of 370). This number approximately equates to the total number of cumulative cases reported in Ghana within the first four weeks of this pandemic (378 as at 9 April).

With the positive test percentage increasing from 3.77% to 6.31% within the same month. This was inconsistent with a decrease in doubling rate to 17-days within that month. As at the 30 July, 17,626 new cases have been reported (a daily average of 587), with the average positive test percentage currently being 9.33%, reflecting much higher positivity rates over the last three weeks.

As at the time of writing, the average positive test percentage over the previous 14-days was 20.95%. As at 30 July, Ghana’s cumulative case count is 37,014 of which 33,365 (90.1%) have been discharged in line with a redefined discharge protocol based on World Health Organisation (WHO) guidance.

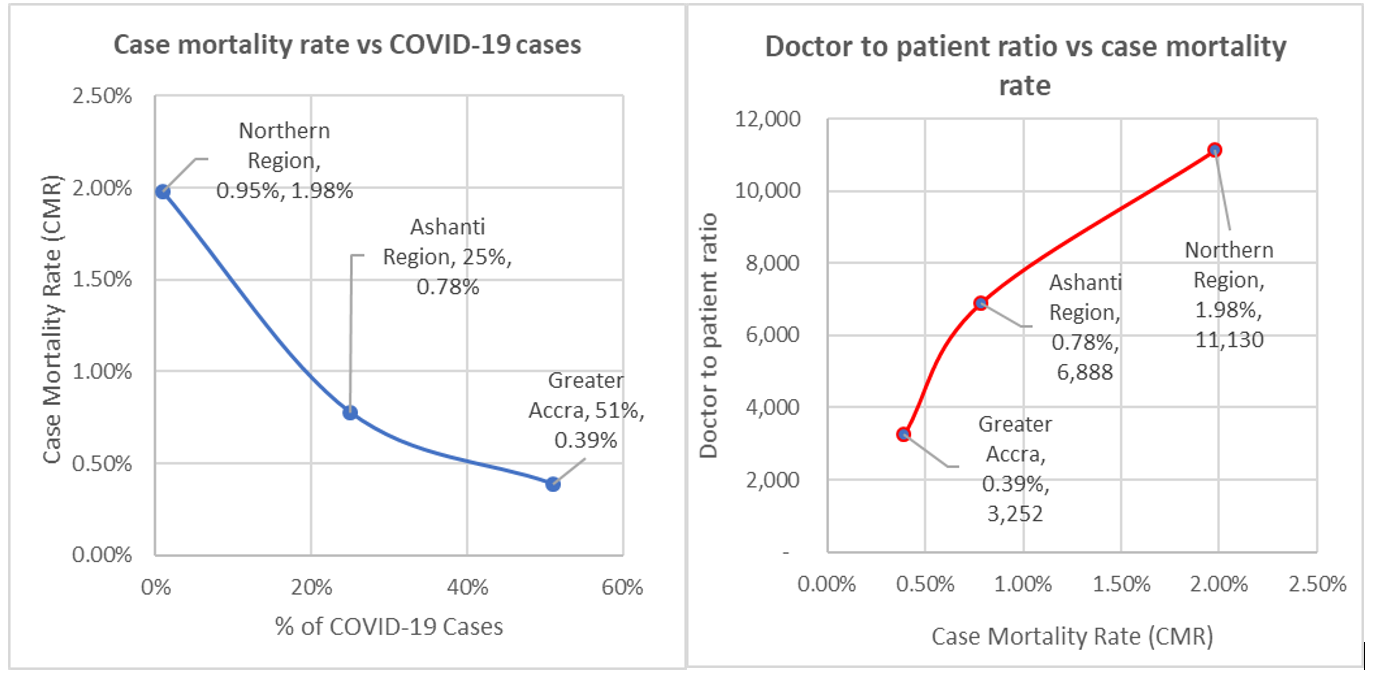

The country has also reported 182 deaths, a Case Mortality Rate (CMR) of 0.49%. However, we note considerable variability across regions when Covid-19 related mortality is compared. For example, Greater Accra, which accounts for 51% (18,822) of all cumulative cases, has a CMR of 0.39% (74 deaths). Ashanti with 25% (9328) of all cumulative cases has a CMR of 0.78% (73 deaths).

In comparison, the Northern Region with 0.95% (354) of all reported cases has a CMR of 1.98% (7 deaths) — see Figure 3. This indicates that that health, human resource and infrastructural disparities are beginning to impact on Covid-19 prognosis.

Ghana’s main treatment centres for COVID-19 and top health personnel are primarily located in Greater Accra, namely Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Ridge Regional Hospital, and the University of Ghana Medical Centre.

2.2 Reproductive number trends

The reproduction number also called the basic reproduction ratio and pronounced “R naught-R0”, measures the contagiousness or transmissibility of the virus. The reproduction number is the number of cases that are “expected to occur on average in a homogeneous population due to an infection by a single individual”.

If R0 is greater than 1, the virus will spread. At the same time, an R0 less than 1 indicates that the virus infection is slowing, and will eventually die out.

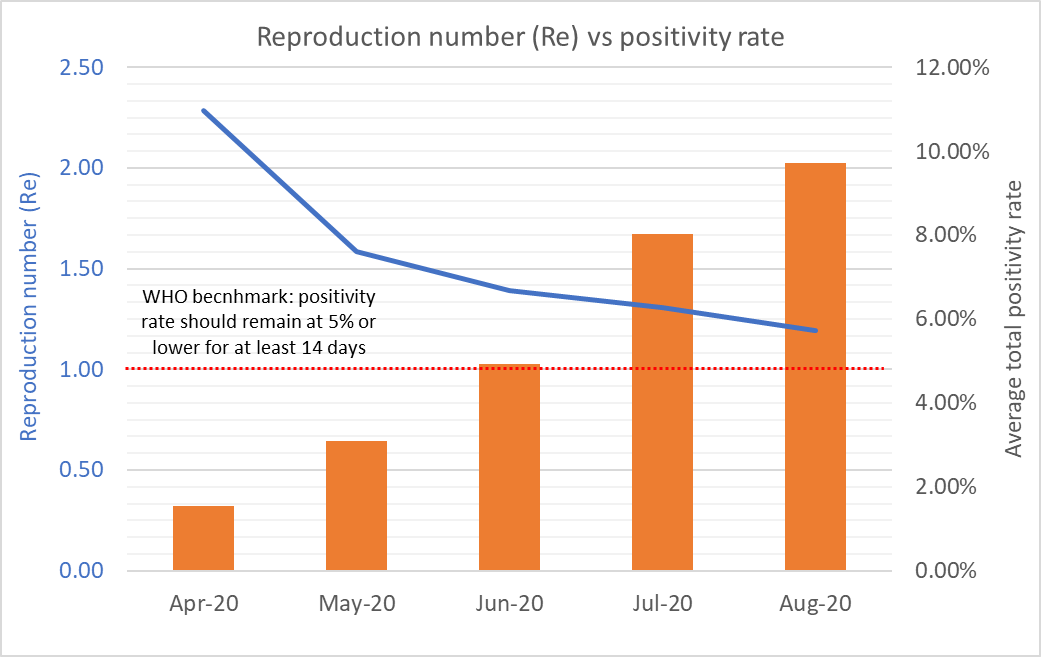

Our first estimates of the R0 in Ghana calculated using data for March was 2.73 (CI: 2.6–2.9), reflecting a high rate of spread at the outset of this outbreak.

By the beginning of Week 3 of the epidemic (26 March — 1 April) and just before the partial lockdown was ordered, the effective reproductive number (Re) had dropped to 1.5 (CI:1.4–1.6), possibly due to public education which had resulted in a gradual adherence to hygiene and social distancing protocols and fear amongst the population.

The Re rose slightly to 1.9 (CI: 1.8–2.0) at the beginning of Week 4 (2 April- 8 April) possibly due to more opportunities for contagion due to human behaviour as people tried to stock up before the lockdown or leave the restricted areas.

These actions could have influenced the occurrence of new infections further away from the main restricted areas.

At the end of the lockdown, 19 April (middle of Week 6) Re was 1.3 (CI range: 1.1–1.5). This was in line with the increasing doubling rate and a slight slowing down of community spread as previously stated.

This value remained stable for another two weeks but has since increased to 1.5 (CI range: 1.3–1.7) as at 12 July also in line with community spread picking up pace towards the end of June. As of 30 July, the Re had dropped slightly to 1.2 (CI range 1.1–1.3).

The effective reproduction number is not decreasing as would be expected in a normal pandemic because the positivity rate has been rising significantly in the last eight weeks.

As can be seen in Figure 3, the monthly change in the positivity rate has jumped from 1.55% in March to 9.71% as at August 2020, reflecting a consistently high monthly net average daily positivity rate of greater than 20%. There would be a need to bring this down to between 3%-12% as per the WHO guidance to get ahead of the virus.

Having a very high positive rate indicates that a country is likely not doing enough testing to find all cases. Thus, to bring the positivity rate down and to get ahead of the virus, we would have to significantly increase the testing capacity from the current average of ~3,000 tests per day to ~9,500 tests per day.

3. Covid-19 cases prevented (abated) by improving testing and isolation time

Here, we provide an analysis of COVID-19 cases prevented by significantly improving tracing, testing and isolation times. Three scenarios will be evaluated as part of this exercise as shown in the table below, namely: (1) status quo, which represents the current 7 to 14-day lag from samples being collected to testing and isolation); (2) recommended case encompassing 2 to 5-day testing and isolation, and an optimal case which equates to 1 to 2-day testing and isolation to prevent further spread.

Using the serial interval and generational time, we estimate 5.3 maximum generations of the virus.

That is, a person who contracted the virus is theoretically able to infect five persons in a chain or infects a second person, who infects a third person, who then infects a fourth person and who also infects a fifth person.

Following this, a three and two-day turnaround time for samples being collected, testing, and eventual isolation of positives for each of the scenarios lead to a significant reduction in generations, and thereby, significantly slow the virus spread in the country.

That is, we move from the maximum of five (5) generations under the status quo to two (2) generations under the recommended case and one (1) generation in the optimal case.

This translates to 19 cases (status quo), 3 cases (recommended case) and 1 (optimal case) potential infection in the general population by an infectee. As can be seen, cutting down on testing and isolation time allows us to get ahead of the virus significantly.

In effect, by increasing the testing and isolation time to three (3) days from the current eight (8) days, you reduce the potential infections caused by one person in the causal chain from 19 to 3 — that is,16 infections prevented.

The following could be practically done to implement the recommended or optimal cases:

• Deploy rapid diagnostic test (RDT) testing to identify potential positives.

• Follow up with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test to confirm.

- All identified COVID-19 positive cases are then removed and quarantined at designated regional/district isolation/quarantine centres (for mild asymptomatics) or hospitals (for severe cases)

4. Social and health sector impact analysis

Though the average number of cases reported daily continues to increase, social behaviours have not improved markedly to help slow the pandemic down.

Even with the President issuing several Executive Instruments (EI) to help with the enforcement of hygiene and social distancing protocols, many still avoid the wearing of facial covering in public spaces.

Footage from many markets indicates that while some are trying to comply with these directives, many citizens continue to flout these while risking punitive action. The culture of handwashing or the use of hand sanitisers is another of the required behaviours that many are struggling to adhere to despite the scientific evidence showing their efficacy in slowing the spread of the virus.

It is as though while much information has been provided through social, print and electronic media, the required public education that will result in behavioural compliance is still not being achieved.

In recent weeks, however, reports that some high-profile public officers have been infected and hospitalised as a result with some speaking publicly about their ordeal seems to be having some impact.

The pandemic has brought significant strain to Ghana’s health system. There has been a constant struggle to obtain Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

Also, as the active case count (which currently is 3,467) increases, the Ghana Health Service (GHS) has struggled to obtain bed space in health facilities to manage those requiring hospitalisation and enough isolation beds for those who cannot self-isolate at home.

These capacity issues have been more pronounced in the Greater Accra and Ashanti Regions. A total of 779 health professionals have been infected in the line of duty including 190 doctors (4 deaths), 410 nurses (1 death), 23 hospital pharmacist (1 death) and 156 allied health professionals (3 deaths). It is important to note that about 50% of all the doctors infected practice in the Ashanti Region.

With the nation having 4,126 doctors in active practise, the doctor to active case ratio is 1: 0.83. This comes with a significant challenge as these doctors must also manage other health conditions while dealing with this pandemic.

Anecdotal evidence also shows that outpatient attendance has dropped as many Ghanaians avoid health facilities for fear of contracting COVID-19 as a hospital-acquired infection. This comes with several challenges, including many patients reporting to health facilities late and unwell with known symptoms of COVID-19.

This result is that about 30% of all COVID-19 related deaths occur less than 24-hours of a patient’s arrival and 60% within 48-hours. Currently, there is no data available on a month to month excess deaths if any as a result of this pandemic in Ghana.

5. Way forward

Our recommendations are summarised as follows:

1. There is a need for timely testing to reporting turnaround within a 24–48-hour cycle. This would significantly reduce the risk of community spread, bring down the Re and allow us to get ahead of the virus.

The status quo option as it currently pertains is contributing to the virus spread as persons remain contagious for between 8-days and 11-days. In any case, testing and reporting of samples outside of this time window due to bottlenecks in the testing regime does not help in reducing the spread of the virus.

Our admiration and commendation go to the hardworking staff at the Noguchi Memorial Research Institute and the Kumasi Centre for Collaborative Research in Tropical Medicine for leading Ghana’s testing efforts, and even championing pooled sampling techniques early in the fight against the virus.

However, these organisations and new testing centres that have been set up need to be adequately resourced to carry out their mandate and improve testing times.

2. There is the need for an active grassroots-based public education regime given COVID-19 is here to stay — at least in the medium term until a vaccine is found.

It is in this vein that we welcome government’s resourcing of the National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE) and other agencies to undertake community health/public education campaigns in collaboration with the metropolitan and district assemblies.

Recent data from the Ghana Statistical Service indicates that most of Ghana’s population over 60 years (could suffer the most from Covid-19) live in Accra, Central and Kumasi. Also, most smokers are in Accra and the Central Region while most households with no water and soap for handwashing are also in Accra and Central Region.

3. The government should aggressively distribute face masks to citizens and enforce the wearing of them.

This could be done at vantage points in the city and on the key transportation entry and exit routes. Also, rationing of PPEs and medical kits need to be reviewed to ensure frontline services and staff get access to these.

Also, we join forces with others who have called on Ghanaians in the diaspora to raise funds to purchase PPEs for health practitioners in Ghana as our little contribution to fighting the pandemic.

We have contributed to such campaigns in our small way and look forward to welcoming more join this noble venture.

4. Finally, as COVID-19 has shown, Ghana needs to chart a new path of sustainably financing its development, premised on the cardinal principles of local sufficiency, efficiency, transparency and value for money.

This pandemic represents an immense opportunity for Ghana to chart a new path of nationhood and real trickle-down economic prosperity. It is time to reboot and rebuild a more inclusive society, where every citizen enjoys from the developmental socioeconomic spin-offs.

***

Authors' Profile

Kwame Sarpong Asiedu is a pharmacist by profession, with 19 years of practice to his name, including lecturing in Ghana and the United Kingdom. He previously held various senior leadership roles at Alliance Boots, now Walgreens Boots Alliance, rising to the position of Head of Pharmacy Operations for East Anglia.

Kwame is a member of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, Institute of Pharmacy Management International, and The Pharmaceutical Society of Ghana. He is also a non-resident Public Health Democracy and Development Fellow at Ghanaian Think Tank CDD Ghana.

Dr Theophilus Acheampong is also an economist and political risk analyst with knowledge and experience working with governments and international institutions on strategic advisory, regulatory and commercial issues in oil and gas, and public finance.

He is an Associate Lecturer at The Centre for Energy, Petroleum and Mineral Law and Policy (CEPMLP), University of Dundee, and Honorary Research Fellow at the Aberdeen Centre for Research in Energy Economics and Finance (ACREEF), University of Aberdeen. He is also a non-resident Senior Fellow at Ghanaian Think Tank IMANI Centre for Policy and Education.

Latest Stories

-

Pan-African Savings and Loans supports Ghana Blind Union with boreholes

6 mins -

Bole-Bamboi MP support artisans and Bole SHS

21 mins -

Top up your credit to avoid potential disruption – ECG to Nuri meter customers

26 mins -

We’ll cut down imports and boost consumption of local rice and other products – Mahama

3 hours -

Prof Opoku-Agyemang donates to Tamale orphanage to mark her birthday

4 hours -

Don’t call re-painted old schools brand new infrastructure – Prof Opoku-Agyemang tells gov’t

5 hours -

Sunon Asogli plant will be back on stream in a few weeks – ECG

5 hours -

ECOWAS deploys observers for Dec. 7 election

5 hours -

73 officers commissioned into Ghana Armed Forces

5 hours -

Impending shutdown of three power plants won’t happen – ECG MD

5 hours -

Ghana shouldn’t have experienced any ‘dumsor’ after 2017 – IES Boss

6 hours -

Lamens flouted some food safety laws in re-bagging rice – Former FDA Boss Alhaji Hudu Mogtari

7 hours -

Afcon exit: Our issue is administrative failure and mismanagement, not lack of talent – Saddick Adams

7 hours -

WAPCo to commence major pipeline maintenance and inspection from November 25

7 hours -

CEO of Oro Oil Ghana Limited Maxwell Commey listed among the 100 Most Influential People Awards, 2024

7 hours