Audio By Carbonatix

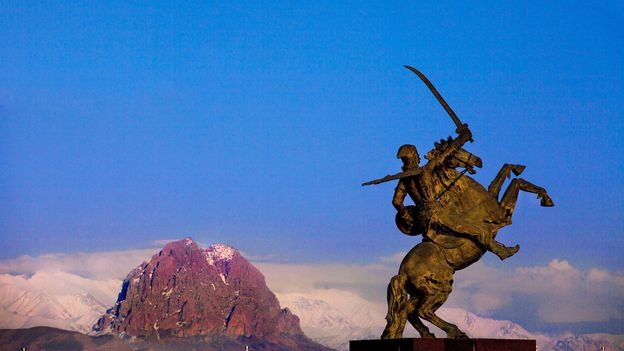

Chances are you’ve never heard of Nakhchivan. Jammed between Armenia, Iran and Turkey on the Transcaucasian plateau, this autonomous republic of Azerbaijan is one of the most isolated outposts of the former Soviet Union and a place few travellers ever visit.

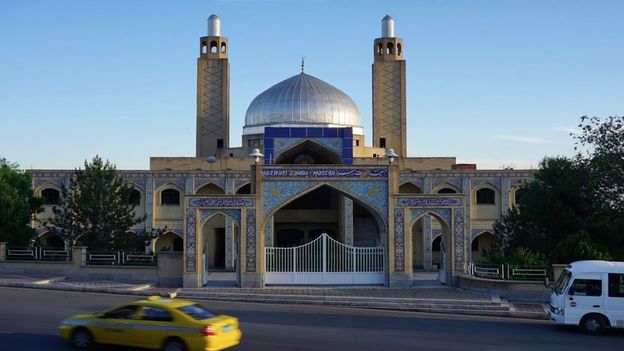

Geographically severed from its nation by an 80-130km strip of Armenia, this 450,000-person slice of Azerbaijan is the world’s largest landlocked exclave, a Bali-sized amalgam of Soviet apartment blocks, gold-domed mosques and arid rust-red mountains wedged between the Black and Caspian seas.

It’s home to a towering mausoleum where the prophet Noah is buried; a medieval mountaintop fortress which Lonely Planet dubbed the “Machu Picchu of Eurasia”; and an eerily clean capital where civil servants plant trees and sweep the streets on weekends. It also happened to be the first part of the crumbling Soviet Union to declare its independence – a couple of months before Lithuania – only to incorporate itself into Azerbaijan a mere fortnight later.

Of course, I didn’t know any of this before recently hopping the last of five 30-minute daily flights from Azerbaijan’s oil-drenched capital, Baku, to Nakhchivan City, the region’s eponymous capital.

In the 15 years or so I’ve spent travelling across the vast outer reaches of the former Soviet Union, I’ve learned Russian, ventured to breakaway micro-nations like Transnistria and monitored elections in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. But a trip to Nakhchivan had always remained elusive. Because of Nakhchivan’s unique position on the Soviet Union’s frontier bordering NATO-member Turkey and Iran, it was something of a secretive exclave largely closed off even to most Soviet citizens. And 30 years after this autonomous republic broke free from the USSR, it still remains relatively unknown to many in the Russian-speaking world and beyond.

Today, anyone with an Azerbaijani visa can enter the region, and while it’s a relatively safe place to visit, authorities continue to be on alert when outsiders show up, in part because very few foreigners do. After alighting from my Azerbaijan Airlines plane and shuffling past the immigration desks, a man whispered in my ear: “The police… they’re talking about you”. “How do they know who I am?” I replied. “They’ve been told that the incoming British citizen is wearing bright red shorts.” It seemed the airport in Baku had called ahead to inform security in Nakhchivan of my arrival, and my garish shorts most likely didn’t help any attempt to blend in.

“You won’t find a single piece of litter lying around Nakhchivan,” my taxi driver-cum-tour guide Mirza Ibrahimov informed me, as we pushed out of Nakhchivan’s impeccably tidy airport in his gleaming black Mercedes and drove through the spotless streets towards the region’s second-largest city, Ordubad.

He was right: my first impression of the exclave was one of surreal, almost shocking, cleanliness. I wanted to ask how the streets, squares and Soviet-era housing complexes we passed remained so tidy, but was distracted by a soaring octagonal pinnacle graced with tiled Islamic geometric patterns in the distance, which Ibrahimov explained holds a special place in the hearts of local residents.

Noah’s Tomb is one of at least five final resting places of the prophet scattered around the world, but don’t tell that to the Nakhchivanis who proudly refer to their motherland as the “land of Noah”. Some scholars say the name “Nakhchivan” is a combination of two Armenian terms, which together mean “place of descent”, while many Azerbaijanis claim it comes from Nakh (“Noah”) and chivan (“place”, meaning “Noah’s place”) in ancient Persian languages.

According to local legend, when the great flood receded, Noah’s ark is said to have landed atop nearby Mount Ilandag, carving out the defined cleft seen on the peak today. Many Nakhchivanis will tell you that the prophet and his followers lived the rest of their days here, and that they are their descendants.

In fact, a few days after Ibrahimov pointed to the mountain’s perforated peak and emphatically recounted that the ark’s hull smashed into the submerged summit, an elderly man on a park bench in Ordubad beckoned me over out of the blue, surely detecting I was a foreigner. “There, on top of that mountain, that’s where Noah’s ark grounded itself,” he said, pointing with his cigarette.

Nakhchivan may be synonymous with Noah, but in the 7,500 or so years since the prophet and his followers descended from Mount Ilandag (or nearby Mount Ararat, depending on whom you ask), their descendants have passed under Persian, Ottoman and Russian rule to form something of a majority Muslim melting pot. In recent decades, an ongoing land dispute with Armenia has remained one of post-Soviet Europe’s last “frozen conflicts”.

In 1988, as Moscow was losing its grip over its constituent republics, war erupted in Nakhchivan’s neighbouring enclave Nagorno-Karabakh in south-western Azerbaijan between ethnic Armenians backed by Armenia and Azerbaijan. As many as 30,000 people died before an unsteady ceasefire was finally struck in 1994. In retaliation, the ethnic Armenian majority controlling the territory closed all railways and roads linking Nakhchivan to the rest of Azerbaijan and the USSR in 1988. Only two small bridges built over the Aras River into Iran and Turkey saved Nakhchivan from starvation and total collapse.

As a result, Nakhchivan’s blockaded residents developed an unwavering sense of self-sufficiency born from scarcity and necessity. Unwilling to remain economically reliant on bridges and neighbours, Nakhchivanians began planting their own food and producing their own goods. And since the rise of Azerbaijan’s second oil surge in 2005 and its subsequent soaring GDP, increased investment from Baku has seen the seeds of this self-sufficient “national” mentality blossom into a fascinating case study in sustainability.

Today, like North Korea, this Azerbaijani exclave is one of the world’s few examples of a loose economic autarky, whereby a kingdom or country survives without much external assistance or international trade. But as I’d come to learn, Nakhchivan’s inward-looking economic policy has a surprising slow-food, organic and ecologically progressive bent – and it’s become a source of pride that has shaped the region’s identity.

Food is venerated in Nakhchivan, and with good reason. “We can eat like this because we can,” Ibrahimov’s friend Elshad Hasanov exclaimed over lunch one day near the Iranian border. He and Ibrahimov reminded me that memories of food shortages are still raw, but since breaking from Soviet policies of economic dependence, Nakhchivan has adopted a strict no-pesticide, all-organic food policy. This health-conscious land-to-table ethos ensures that the Balbas breed of sheep you’re eating come from Nakhchivani farms; the fish from Nakhchivani lakes; the wild dill, aniseed terragon and sweet basil from Nakhchivani foothills; the produce from Nakhchivani orchards and even the salt from underground Nakhchivani caves.

Soon, our table groaned under an entire carcass of tender lamb. This was accompanied by platters of vegetable-seared mangal salads, cheeses, lavash flatbreads, kebabs, freshly caught trout, beer and vodkas infused with a selection of the 300 herbs grown in the nearby mountains – each offering a natural remedy for one ailment of another.

When I asked about the motive behind Nakhchivan’s organic, locavore movement, Hasanov cited wellbeing. “Our people are healthy, and we don’t suffer from the same ailments as before, because we only eat what is natural,” he said. As I listened, I bit into a large plum tomato and a fresh burst of sweetness filled my mouth. It was, undoubtedly, the best tomato I had ever tasted.

Nakhchivan’s health kick doesn’t stop at GMO-free crops. Fourteen kilometres outside Nakhchivan City is Duzdag Salt Cave, an impressive, no-expenses-spared sanatorium built deep inside a former Soviet salt mine. The cave’s website assures medical tourists that the complex’s 130m tonnes of pure natural salt can cure a whole range of respiratory illnesses, from asthma to bronchitis.

Nakhchivan’s 30-degree heat evaporated as Ibrahimov and I descended into the dark, chilly grotto. Ibrahimov, a heavy smoker and a convert to the benefits of spleotherapy, or “cave therapy”, inhaled deeply. “We’ve had visitors come here from all over the world,” he said. “One guy from Uruguay who had suffered from bad asthma came last year and left cured.” Just then a group of young schoolchildren and their teachers checked in to spend the night in the cave soaking up the salt and silence.

Back above ground, I was determined to get to the bottom of the capital’s obsession with cleanliness. By all accounts, Nakhchivan is considered the cleanest city in Azerbaijan, if not the whole of the Caucasus, and for good reason. Everywhere you look, the motorways are perfectly paved, the streets immaculately swept, the trees neatly trimmed and the weeds swiftly pulled.

According to a detailed report published by the Norwegian Helsinki Committee, much of this achievement is down to the exclave’s public-sector employees – such as teachers, soldiers, doctors and government workers – who volunteer to clean the streets on their days off.

What’s more, in an effort to replenish the forests that were burned for fuel during the blockade, residents are also encouraged to plant trees when they’re not working or sweeping up the streets. This practice is rooted in a Soviet-era practice called subbotnik: a now archaic concept of voluntarily, unpaid labour. Or as described by some during Soviet days, work in “a voluntary-compulsory way".

One Saturday morning during my visit, Ibrahimov stopped his Mercedes and pointed at verdant fields in the near distance. Under an unforgivingly bright sun, small groups of people were huddled together. “They’re planting fruit trees,”he said. On the surface, the practice of subbotnik seems altruistic enough: with each tree planted, the exclave’s lungs expand and grow stronger, while increasing the region’s supply of its much-cherished fruits.

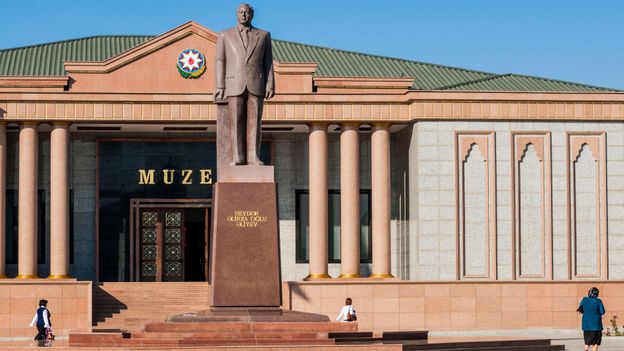

Yet, according to the same Norwegian Helsinki Committee report, anyone who objects to this “volunteer” work must resign from their state job immediately, one employee of Nakhchivan’s Ministry of Economic Development admitted. A Nakhchivan State University professor acknowledged that Vasif Talibov, the current head of Nakhchivan and considered by many as an authoritarian ruler, is gaining tremendous income from this free labour.

By the end of my visit, I began to wonder if Nakhchivan’s clean, green image is somewhat akin to a place like Singapore, where public tidiness is driven by a mixture of low-cost labour and fear of governmental repercussions. Nakhchivan is a puzzle that I couldn’t solve: is it a progressive and self-sufficient exclave populated by altruistic volunteers, a carefully staged hermit fiefdom or a complex combination of the two?

What is certain is that this insular exclave felt like nowhere I had ever been before: a former “secretive” USSR stronghold where young people still whisper to one another at restaurants to avoid being overheard but boldly boast of the progressive virtues of farm-to-table cuisine to outsiders; where civil servants carry out unpaid manual labour on weekends despite living in a nation whose GDP has skyrocketed more than 300% in the last 15 years; and whose residents proudly tie their cultural identity to a prophet who sailed in from afar but whose local government now walls itself in.

I’m not sure what the future may hold in this confounding beacon of locavore-loving isolationists, but I hope they’ll keep their doors open so I can find out for myself.

Latest Stories

-

Ghana’s global image boosted by our world-acclaimed reset agenda – Mahama

5 minutes -

Full text: Mahama’s New Year message to the nation

6 minutes -

The foundation is laid; now we accelerate and expand in 2026 – Mahama

25 minutes -

There is no NPP, CPP nor NDC Ghana, only one Ghana – Mahama

27 minutes -

Eduwatch praises education financing gains but warns delays, teacher gaps could derail reforms

41 minutes -

Kusaal Wikimedians take local language online in 14-day digital campaign

1 hour -

Stop interfering in each other’s roles – Bole-Bamboi MP appeals to traditional rulers for peace

2 hours -

Playback: President Mahama addressed the nation in New Year message

2 hours -

Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union call for strong work ethics, economic participation in 2026 new year message

4 hours -

Crossover Joy: Churches in Ghana welcome 2026 with fire and faith

4 hours -

Traffic chaos on Accra–Kumasi Highway leaves hundreds stranded as diversions gridlock

4 hours -

Luv FM Family Party in the Park: Hundreds of families flock to Luv FM family party as more join the queue in excitement

4 hours -

Failure to resolve galamsey menace could send gov’t to opposition – Dr Asah-Asante warns

4 hours -

Leadership Lunch & Learn December edition empowers women leaders with practical insights

4 hours -

12 of the best TV shows to watch this January

5 hours